When To Catch a Predator first aired, in 2004, as part of NBC’s Dateline news magazine show, it became a sensation. Equal parts news, moral crusade and shock television, the series gripped audiences with a soon-familiar ritual: a man walks into a suburban home expecting an inappropriate encounter with a minor, only to be met by Chris Hansen, the show’s host, and his camera crew.

The resulting marriage of panicked perpetrators and vigilante justice, with entertainment and a public-service element thrown in, spawned internet memes and parodies on Saturday Night Live, on 30 Rock and at Hollywood award ceremonies.

Hansen, a heavily decorated journalist with 10 Emmys and five Edward R Murrow Awards, became a guest on The Oprah Winfrey Show and featured on The Simpsons. Arrests were made, and generations of teenagers were warned about a new breed of internet predator.

“There was a moment when the show came out in the early 2000s,” says David Osit, the director of Predators, a new film revisiting the series. “It was a very specific moment in the internet’s history. Everyone was online, but not everyone understood the internet. That fear created a space for public-service announcements and shows like this.”

Predators shares an intersecting theme, yet very little DNA, with the vogue for chronicling the wild west of early reality television, projects including Apple TV’s Dark Side of Reality TV and Netflix’s Fit for TV: The Reality of The Biggest Loser. Osit’s uneasy and contemplative exploration of To Catch a Predator is neither a drive-by nor nostalgia-driven but a reckoning with the show’s enduring appeal.

“I watched it, but back then it wasn’t a show you were a fan of,” he says. “There weren’t T-shirts or message boards. It was still a news programme. I watched it and then forgot about it. What’s unique is that it only aired under 20 times over three years, yet it still has name recognition in the United States across generations.”

Osit, previously best known for Mayor, a 2020 documentary portrait of Musa Hadid, an elected official in Ramallah, didn’t set out to make this kind of film.

“I never expected to make a true-crime documentary, let alone one about To Catch a Predator,” he says. “I stumbled on to the raw footage that the online fandom community had been preserving for about 20 years. They’d been collecting it through Freedom of Information Act requests: raw footage, defence packages, depositions.”

David Osit: ‘It’s not a film about predators so much as it’s a film about how shows like this make us feel.’ Photograph: Andreas Rentz/Getty/ZFF

David Osit: ‘It’s not a film about predators so much as it’s a film about how shows like this make us feel.’ Photograph: Andreas Rentz/Getty/ZFF

That material does not make for easy viewing. Lengthy footage of men caught in sting operations – pleading, crying, begging to go free – is juxtaposed with chilling chat logs of them seeking victims online. That dichotomy is murkier than the neat, cathartic and sometimes comical gotcha moments of To Catch a Predator.

“I started watching this material, and that’s what sparked my interest,” Osit says. “I remembered the show as this sensational thing. And then suddenly I was watching 75- or 80-minute single-shot takes of someone’s life ending in slow motion. If you’re human it’s hard not to feel something watching that, regardless of what someone’s done or might have done.”

That acute discomfort – the impulse to look away and the compulsion to keep watching regardless – forms the spine of his film. “I kept thinking, I don’t know how to feel about this,” Osit says. “That was such a strange sentiment that I thought, What if I made a film about that feeling? So it’s not a film about predators so much as it’s a film about how shows like this make us feel. Or stop us from feeling.”

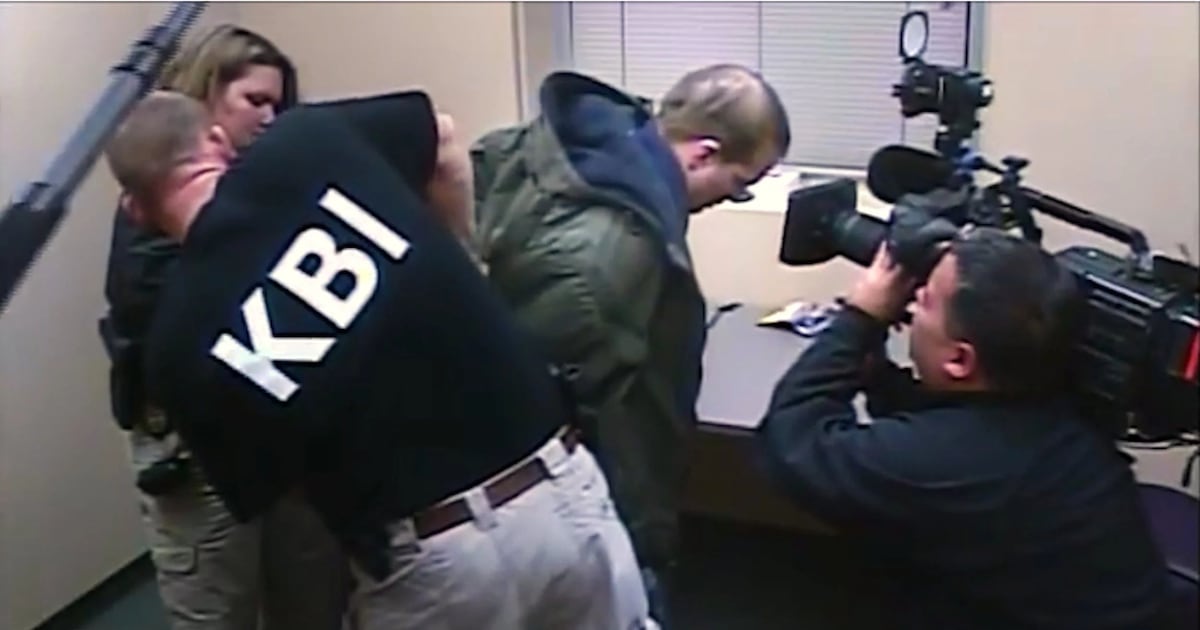

Predators also chronicles the queasy relationship between broadcast television and law enforcement in one key incident. In arguably the most controversial episode, a sting in Texas went horribly wrong: Bill Conradt, an assistant district attorney, died by suicide as police, accompanied by an NBC camera crew, attempted to serve a search warrant on him.

Osit includes unaired footage and producer interviews, outlining the alliances between the police and the network, and demonstrates how the quest for ratings could eclipse any duty of care.

The effect is typical of Osit’s careful, contextualising use of out-takes. The unedited footage forced him to confront what the show had obscured.

“I didn’t remember any details, just that it had that train-wreck energy,” he says. “Watching the raw footage made me feel disgusted. Horrified, really. The original show was edited to make you want to watch more. It was built on a formula. The humour in the interactions between Chris Hansen and the men. That humour is gone in the raw footage. It’s hard to find anything funny in it.”

Predators: David Osit and Chris Hansen

Predators: David Osit and Chris Hansen

Reruns of To Catch a Predator continue to attract global viewers. Chris Hansen, whose interview for Predators provides the film’s considered denouement, maintains a dedicated following through TruBlu, the true-crime-oriented platform he cofounded in 2020. A year earlier he resurrected the To Catch a Predator format for a syndicated segment called Hansen vs Predator. About 435,000 subscribers tune into his YouTube channel for adjacent content, including Predators I’ve Caught.

“I approached him early in production,” Osit says. “I told him the truth: that I was interested in how he, in many ways, seemed like the godfather of this genre where journalism and law enforcement merge to create entertainment. He agreed with that assessment.”

Hansen’s willingness to collaborate, Osit explains, came partly from his continuing mission. “I was also interested in the fact that he was still doing the show. He’d rebooted it on his own network, free from the constraints of broadcast standards. He was going direct to consumer, which wasn’t possible 20 years ago but is now almost the norm. I wanted to follow him doing that.”

Hansen’s work was only the beginning, however. Across the United States and Europe, self-styled “predator catchers” have replicated the To Catch a Predator format on YouTube, TikTok and livestreaming platforms.

In common with the NBC original, groups such as Predator Exposure, in England, Creep Catchers, in Canada, and Dads Against Predators, in the United States, stage amateur sting operations, luring potential offenders into filmed encounters, often showing names, faces and chat logs. That information can potentially reach millions of viewers before authorities intervene.

Osit’s film tags along with one such activist: Skeeter Jean, a self-styled “Chris Hansen impersonator” who has attracted more than two million YouTube subscribers.

“In Ireland and the UK, amateur predator-hunting is a huge phenomenon, maybe even more per capita than in the States,” Osit says. “There’s a direct lineage between To Catch a Predator and that. My film tries to get at the in-between. And that in-between is us. At some point we decided we enjoy entertainment that straddles the line between empathy and cruelty.”

He approached everyone with curiosity, he says. “I may disagree with them, but I wasn’t trying to caricature anyone. I wanted to do what To Catch a Predator never did: look beyond archetypes and understand what drives people. That sincerity helped me build trust.”

Skeeter Jean has responded positively to the finished work. “He even posted about it on social media,” Osit says.

Since it premiered at Sundance Film Festival, Predators has amassed a 98 per cent approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Not everyone is a fan, though. “It has run the gamut,” the film-maker says. “Some people think I’m asking them to have sympathy for child predators. I’m not. But it’s fascinating that people react that way. It shows how afraid we are of seeing humanity in people we’ve decided are monsters.”

Predators forced Osit, who has previously worked as an editor on true-crime exposés of the NXIVM cult (in The Vow) and 4Chan (in The Antisocial Network), to confront his own complicity as a documentarian.

“Chris and I actually have things in common,’ he says. “We’re both film-makers using reality to create stories, both incentivised to make them more entertaining. That’s really what brought the film to life: understanding that what I was doing sometimes mirrored what I was criticising.”

Predators is an impressively intelligent project.

“There’s a lot of righteous documentary film-making, especially from the left, where films are made to affirm or anger rather than to question. I wanted to make something more challenging than that.

“In some ways this film is an indictment of what I do for a living. I don’t know if I’ll ever make certain films the same way again. It really changed me.”

Predators is in cinemas and available from dogwoof.com from Friday, November 14th; it streams on Paramount+ from Monday, December 8th