Listen to an audio version of this story:

Listen to an audio version of this story:

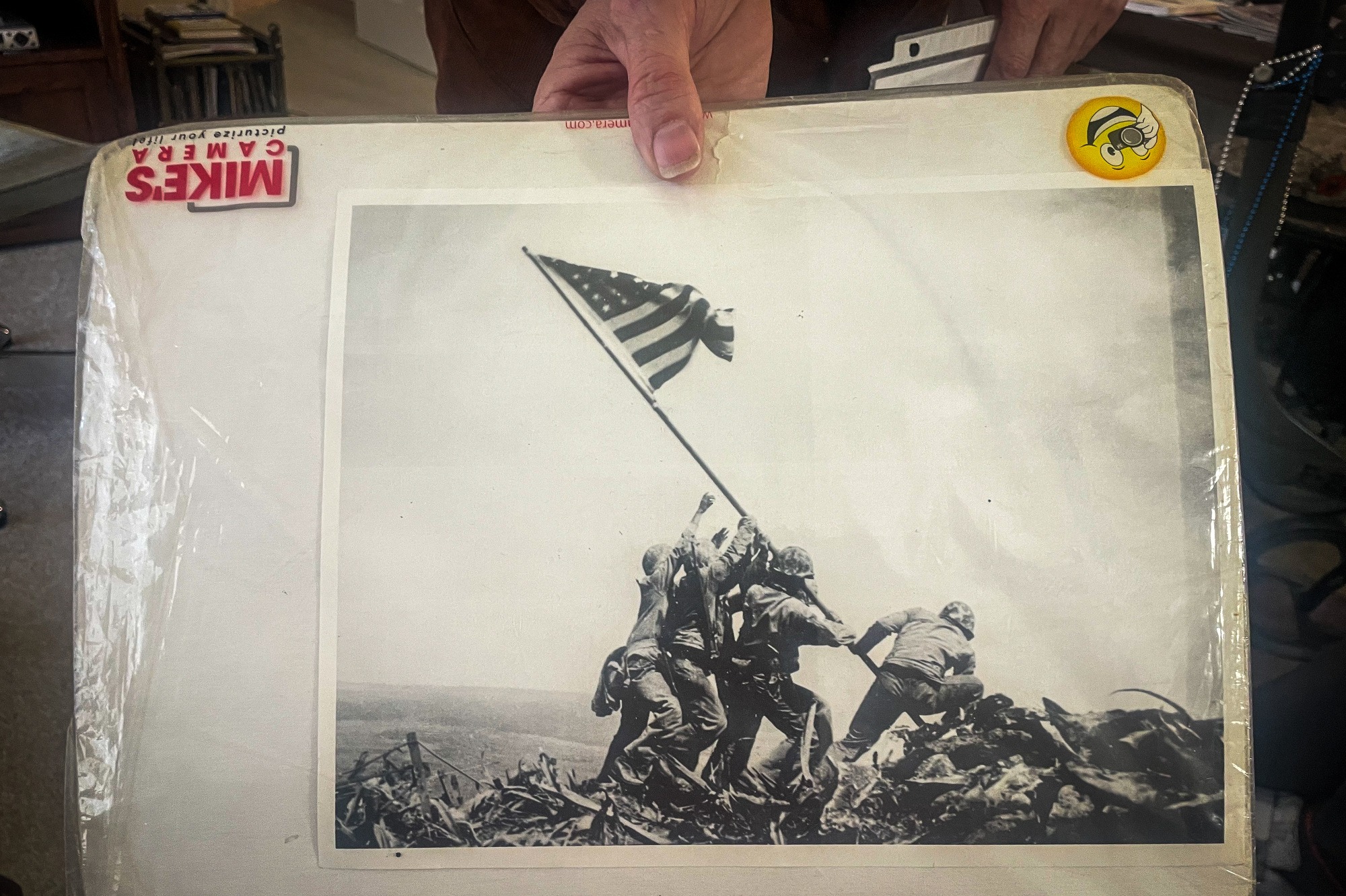

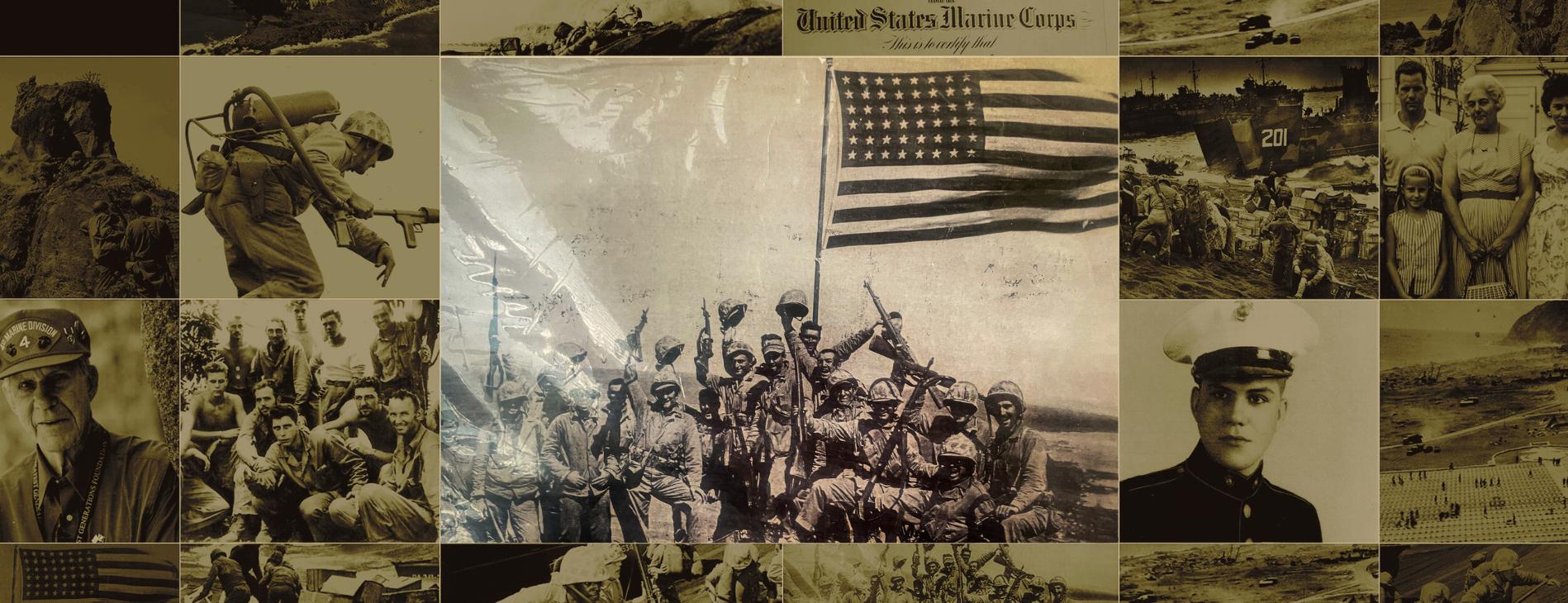

It’s one of the most enduring images from World War II

Six Marines raising the American flag on the island of Iwo Jima in 1945

The Pulitzer Prize-winning photo has been on stamps and posters, and was the inspiration for the Marine Corps War Memorial statue in Arlington, Va.

Inside Jim Blane’s apartment in Denver, a print of the image hangs prominently on the wall. It has a special importance for him — he is one of the last living combat veterans who was there that day.

“When they raised that flag, we didn’t know it was gonna become as famous as it was. But I understand why,” he recalled recently.

In this Oct. 12, 2025, photo taken in Denver, Colo., Jim Blane looks at his Joe Rosenthal photograph of Marines standing atop Mt. Suribachi on Feb. 23, 1945.

In this Oct. 12, 2025, photo taken in Denver, Colo., Jim Blane looks at his Joe Rosenthal photograph of Marines standing atop Mt. Suribachi on Feb. 23, 1945.

It took Blane 50 years to begin to talk about his time in combat; he saw such awful things, and so many of his fellow Marines and friends didn’t make it home.

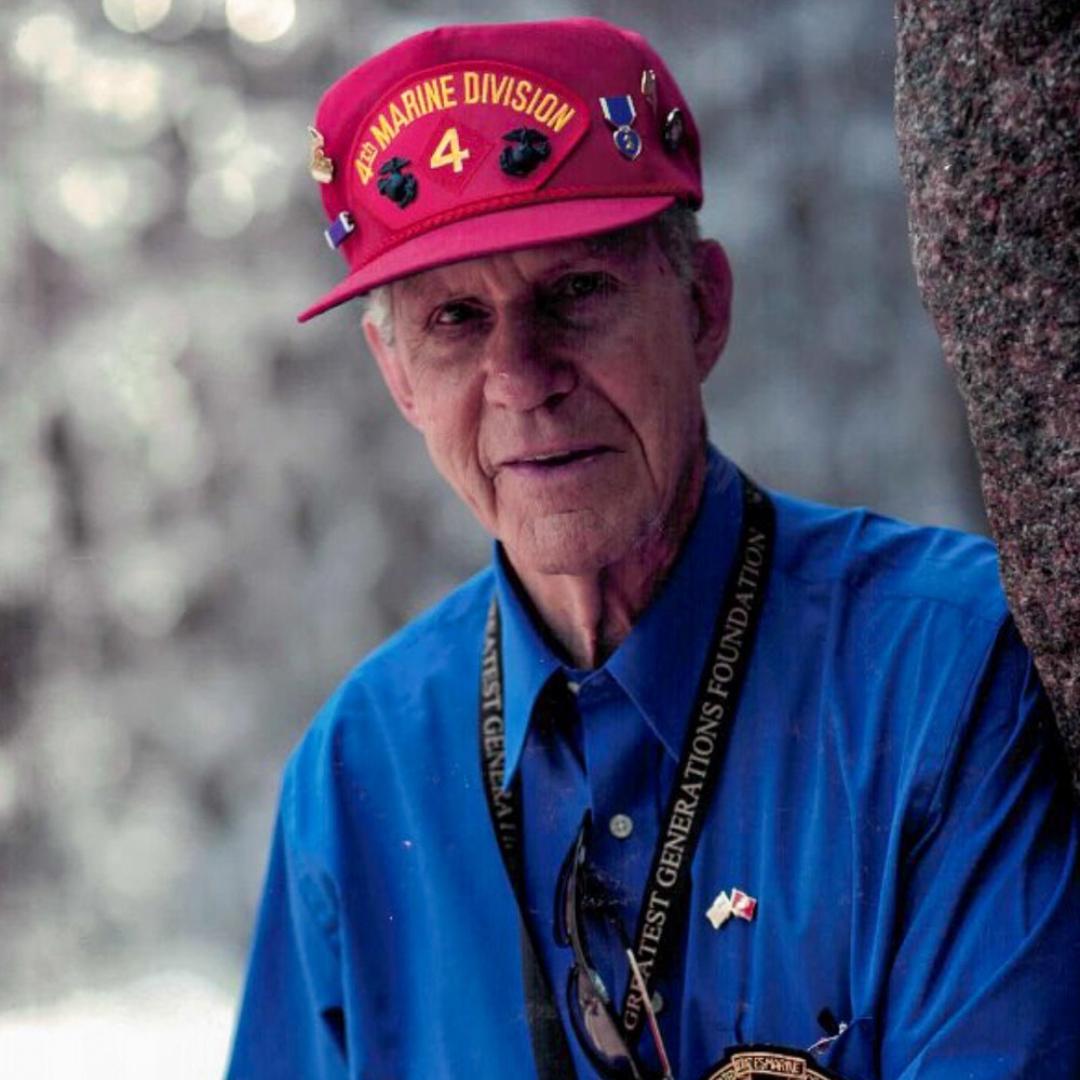

But as he prepares to celebrate his 101st birthday this month — just as the U.S. Marine Corps marks its 250th anniversary — the veteran says when it comes to the war and Iwo Jima, he’s at last, wide open.

‘Nothing but volcanic ash’

During the final year of the war, as the United States pursued its fight against Japan, one tiny volcanic island way out in the Pacific became a crucial location.

Capturing Iwo Jima would provide the U.S. with a strategic landing base for the fighter aircraft and bombers it was sending toward Japan, and it would remove the island as a strategic guard post for the Japanese.

Blane first set foot on the island 80 years ago as a Corporal with the 4th Marine Division; he remembers it as a desolate place.

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteMarines go ashore on Iwo Jima.

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteMarines go ashore on Iwo Jima. Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteAmericans fighting on Iwo Jima.

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteAmericans fighting on Iwo Jima.

“At Iwo, there’s nothing but volcanic ash. There was no dirt or anything there what we call dirt,” he said.

Military leaders thought they’d quickly take the island from the Japanese. But with their opponents dug in through a network of tunnels and bunkers, the battle stretched for 36 grueling days. It became one of the defining conflicts of the Pacific campaign and the deadliest battle in Marine history. Nearly 7,000 were killed, and 20,000 more were wounded.

“The Marine Corps was chosen to finish that war. And we did what we were told to do,” said Blane. “We went ahead and finished it up the island. We lost more of our guys, but we did secure the island; the Japanese surrendered.”

Blane was still in high school when the attack on Pearl Harbor pulled the U.S. into World War Two. He remembers that at the time, most people in his hometown of Peoria, Illinois, weren’t paying much attention to the conflict.

“But they paid attention if they had relatives that were drafted,” he said, “because that’s when they had the draft.”

Blane didn’t want to just wait to be drafted, so not long after his 18th birthday, he and two friends hitchhiked to Chicago to enlist in the Marines. He was sent to training at Camp Pendleton in Southern California and then to Hawaii.

It was the first time he’d ever been out of state, and from that point on, “life,” he said, “was Marine Corps life, if you know anything about it.”

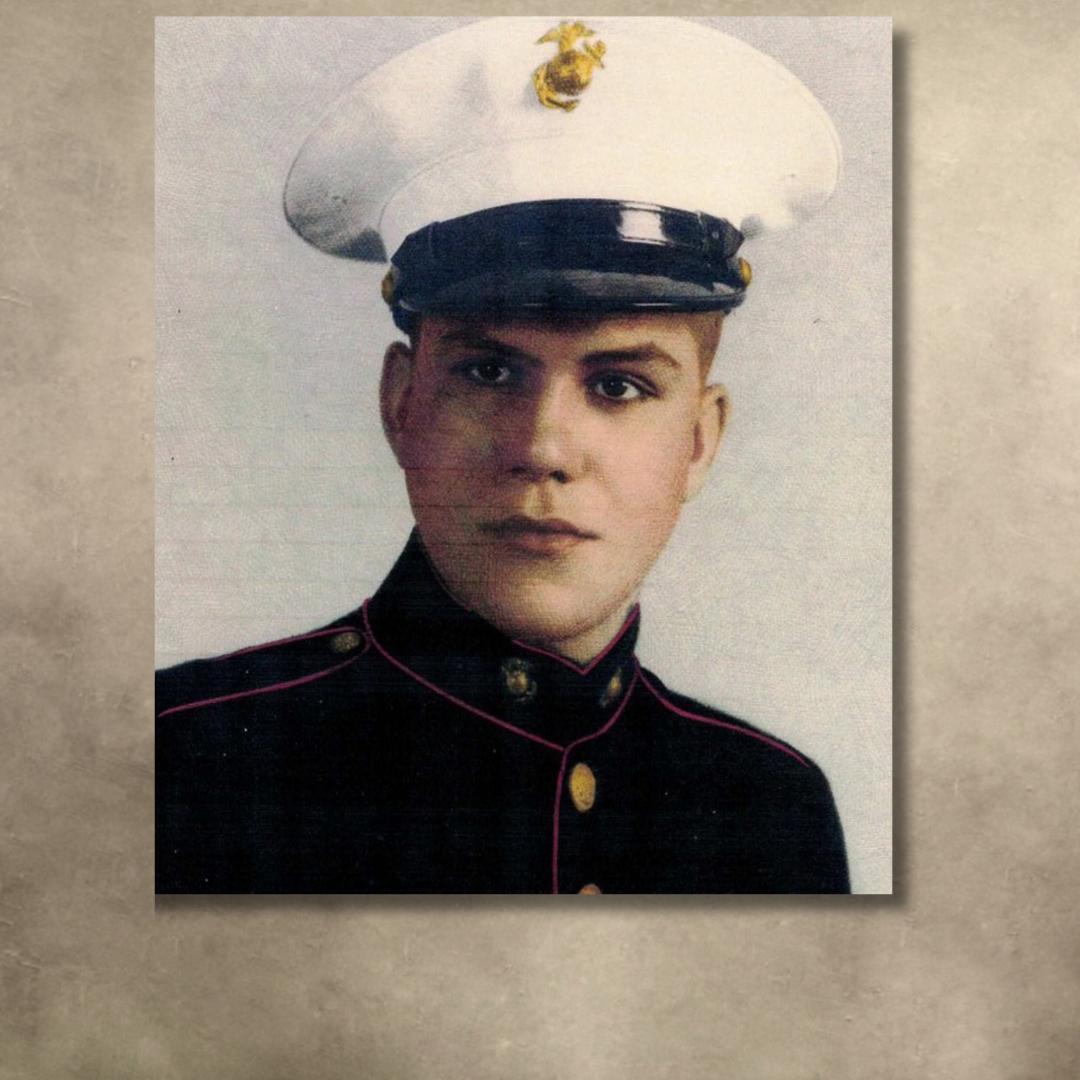

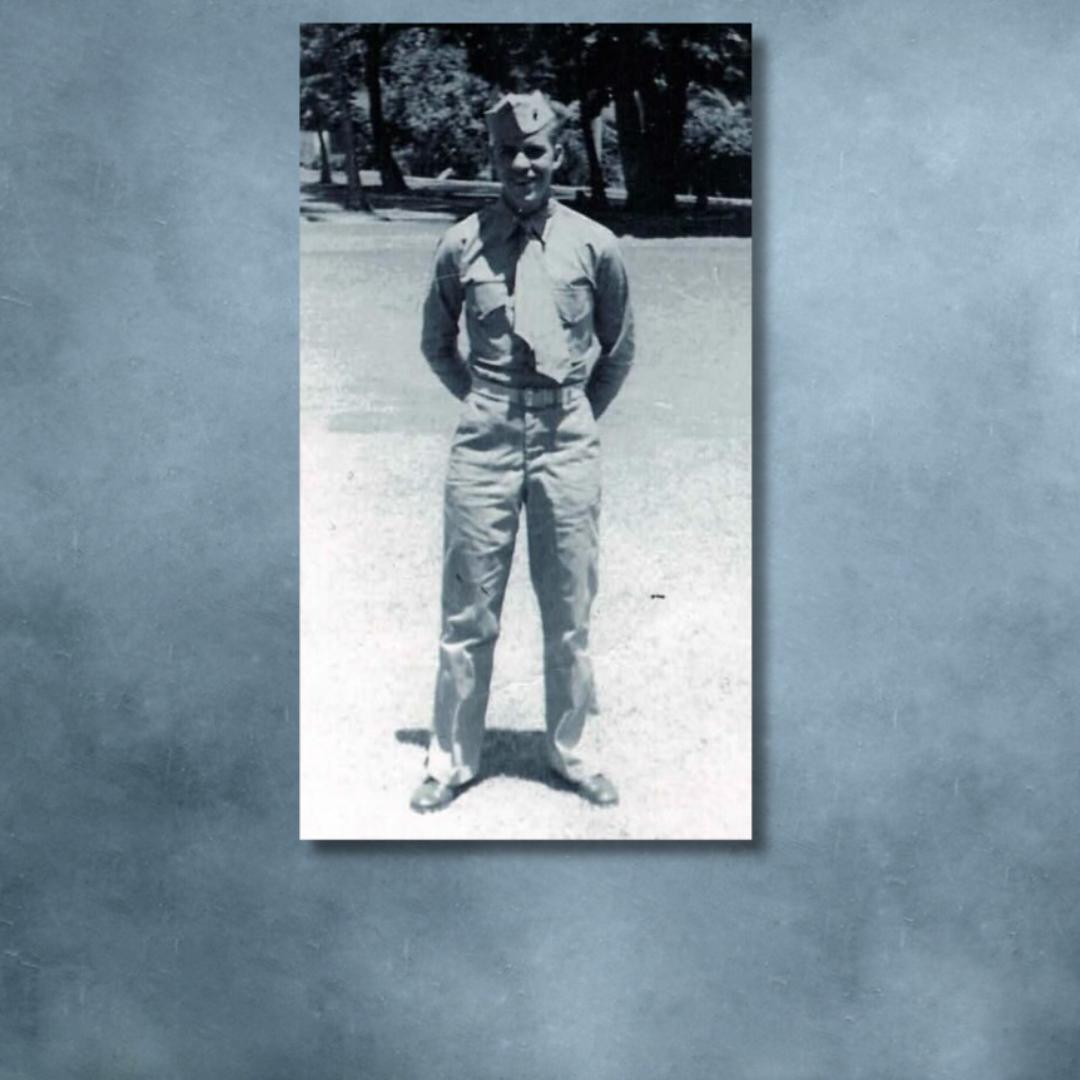

Photo: Jim Blane at 18 when he enlisted in the Marines, 1943, in Chicago, Ill.

Blane wanted to see action on the battlefield. But that goal was almost derailed at training camp, when a fellow Marine spotted him typing a letter to his parents.

“And he said, ‘Well, well, we now find you a typist.’ So he got the leader of the camp on the phone and said, ‘John, I found you a typist.’ Well, from that day on, I did nothing but type every doggone thing in the entire camp.”

For a while, it looked like he might be assigned to an administrative job and spend the war behind a desk. But that didn’t sit well with Blane, so when training camp ended, he volunteered to go into the part of the Corps where he was assured to see some action.

“There were times when I regretted it. But I didn’t want to be a typist my whole career,” he explained.

Photo: Jim Blane at age 18 in Maui at training camp before he was deployed to the Pacific campaign. 1943.

‘I did what I had to do’

Blane was sent to the Pacific theater as a member of the 4th Marine Division. He fought on the Marshall Islands, then Saipan and Tinian on the Marianas. But it was his final assignment that left the biggest impact on his life: Iwo Jima.

The fighting there was long and brutal. Twenty thousand Japanese soldiers died trying to hold the island.

“I did what I had to do to try to kill more Japanese people,” he said. “My buddies and I did it whether we liked it or not.”

One particular firefight left a lasting effect. He’d been assigned guard duty to protect American supplies when a group of Japanese soldiers sneaked out of the darkness to try to break in, desperate to add to their own exhausted rations, “’cause they ran out of everything too.”

Unloading supplies on Iwo Jima.

Unloading supplies on Iwo Jima. Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteAn American Marine armed with a flamethrower on Iwo Jima.

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteAn American Marine armed with a flamethrower on Iwo Jima.

In the fight that followed, he killed three Japanese soldiers. But he also took fire — a bullet grazed the top of his helmet, while another hit his foot, going straight through his shoe and out the other side.

As he described it, the shooting “wasn’t much of an injury,” or at least, it wasn’t something that got much attention at the time.

“It got worse later on,” he said. “But I never seen a doctor until we finished taking Iwo Jima.”

Instead, a medic wrapped the foot in cloth, and Blane kept walking on it.

Blane told this story while sitting in a recliner in the living room of his apartment in Denver, all these years later. He leaned over to take off his shoe and sock, to touch where the bullet hit.

“Between the bones. It’s a soft part of your foot,” he observed, remarking that, after 80 years, there’s no visible scar.

Jim Blane sits in his recliner in his apartment, holding a small statue of the famous photo of Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima, on Oct. 12, 2025, in Denver, Colo.

Jim Blane sits in his recliner in his apartment, holding a small statue of the famous photo of Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima, on Oct. 12, 2025, in Denver, Colo.

Blane’s son, Phil, who sat nearby during the interview, said he’s heard the story many times, but it still amazes him that his father continued on in the field with that injury.

“It’s a toughness thing,” Phil observed.

Blane responded that as tough as the situation was, you couldn’t back off; “Marines don’t do that.”

Blane was later awarded a Purple Heart, but back on the island, he got a new assignment: body detail, searching for casualties on the battlefield.

“I had to go up and drag bodies out of the volcanic ash down to the place where the medical people were trying to save some of ’em.”

Blane would climb up the ashy slopes, get two bodies at a time and carry them back down. It was wrenching work, and he eventually talked the higher-ups into letting him out of it, “because I didn’t like doing that doggone duty.”

Wikimedia CommonsBurying the dead on Iwo Jima.The famous photo

Wikimedia CommonsBurying the dead on Iwo Jima.The famous photo

Blane has his military medals displayed inside an oval frame on the wall of his apartment, near Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal’s famous picture of the flag raising. He cradles a small statue of the image in his lap as he talks about Iwo Jima.

Rosenthal died in 2006. In an article he wrote about taking the photo, he described the Marines on Iwo Jima as ‘magnificent.’

“The mountainside had a porcupine appearance of bristling all over, what with machine and anti-aircraft guns peering from the dugouts, foxholes and caves,” Rosenthal wrote, of his climb up Mount Suribachi. “There were few signs of life from these enemy spots, however. Our men were systematically blowing out these places, and we had to be on our toes to keep clear of our own demolition squads.”

U.S. Marines raise the American flag on the summit of Mt. Suribachi on Feb. 23, 1945, during the Battle of Iwo Jima against the Japanese.

U.S. Marines raise the American flag on the summit of Mt. Suribachi on Feb. 23, 1945, during the Battle of Iwo Jima against the Japanese. Jim Blane’s son shows Jim’s photo of the Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima on Oct. 12, 2025, in Denver, Colo.

Jim Blane’s son shows Jim’s photo of the Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima on Oct. 12, 2025, in Denver, Colo.

Blane said he was on hand and watched as Rosenthal took the picture that day. They were just five days into the battle, but it was an important moment. The Marines had captured the highest point on the island.

“Some of the guys went into tears, and I got choked up over it myself,” he said of the flag-raising.

But despite the powerful milestone, the full battle was far from over. Three of the six men in the picture did not survive the fight to take Iwo Jima.

In the fall of 1945, with the war over, Blane finally got medical care for his foot. He was sent to recover at a hospital in Farragut, Idaho, in a location that’s now become a state park. That’s when he physically received his initial Purple Heart medal.

As he was lying in his hospital bed, a man walked by with a little box holding numerous Purple Heart medals and took one out.

“They pinned it on the blanket I had laying over my upper body. And they didn’t have a box with it.”

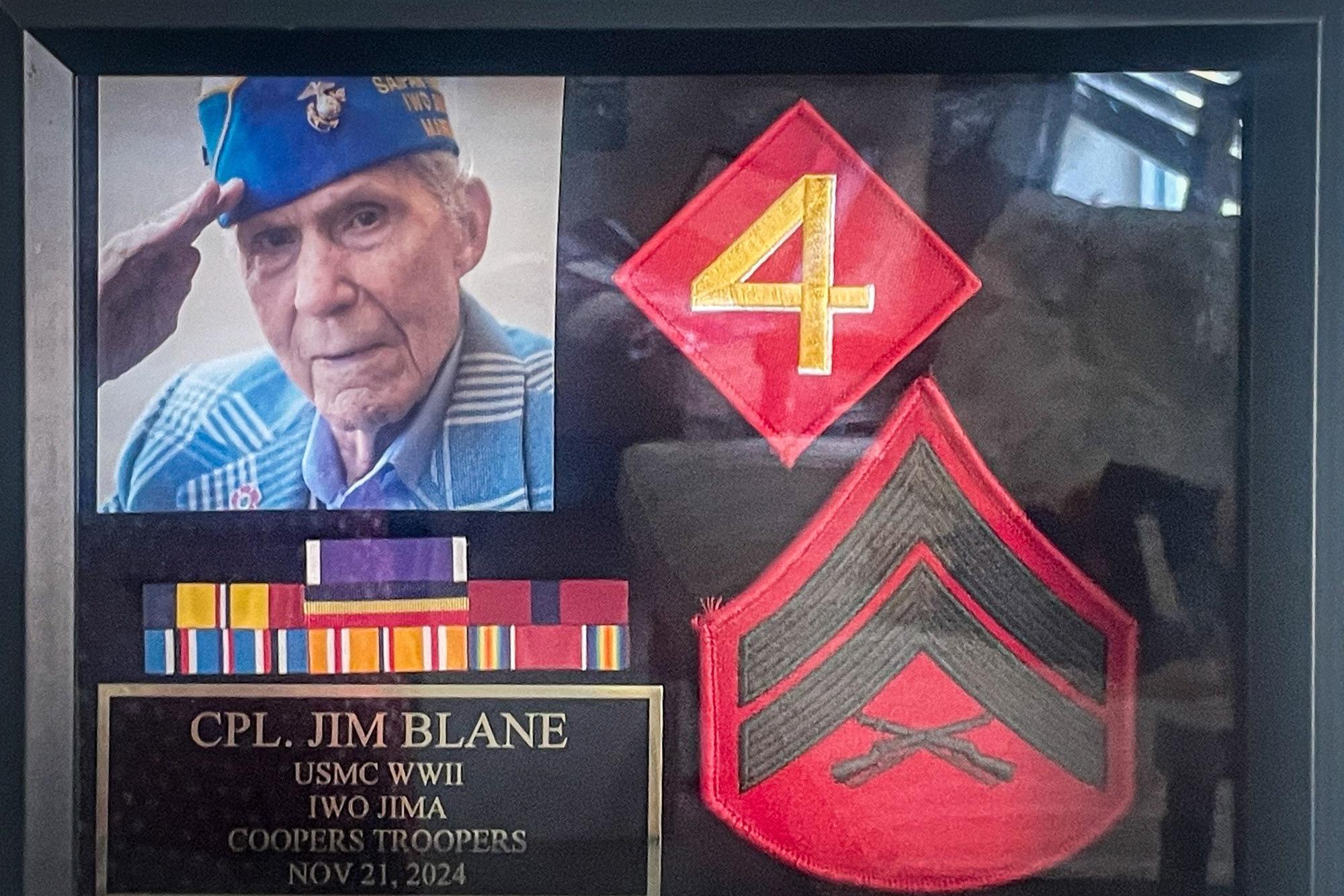

Bente Birkeland/CPR NewsThis photo, taken Oct. 12, 2025, shows a framed picture in Jim Blane’s Denver apartment that displays his military medals, including his Purple Heart.

Bente Birkeland/CPR NewsThis photo, taken Oct. 12, 2025, shows a framed picture in Jim Blane’s Denver apartment that displays his military medals, including his Purple Heart.  Tom JacksonThis photo, taken on Oct. 12, 2025, in Denver, Colo., shows a framed picture in Jim Blane’s apartment, highlighting the 4th Marine Division, in which he served. The Division experienced heavy casualties in the Battle of Iwo Jima.

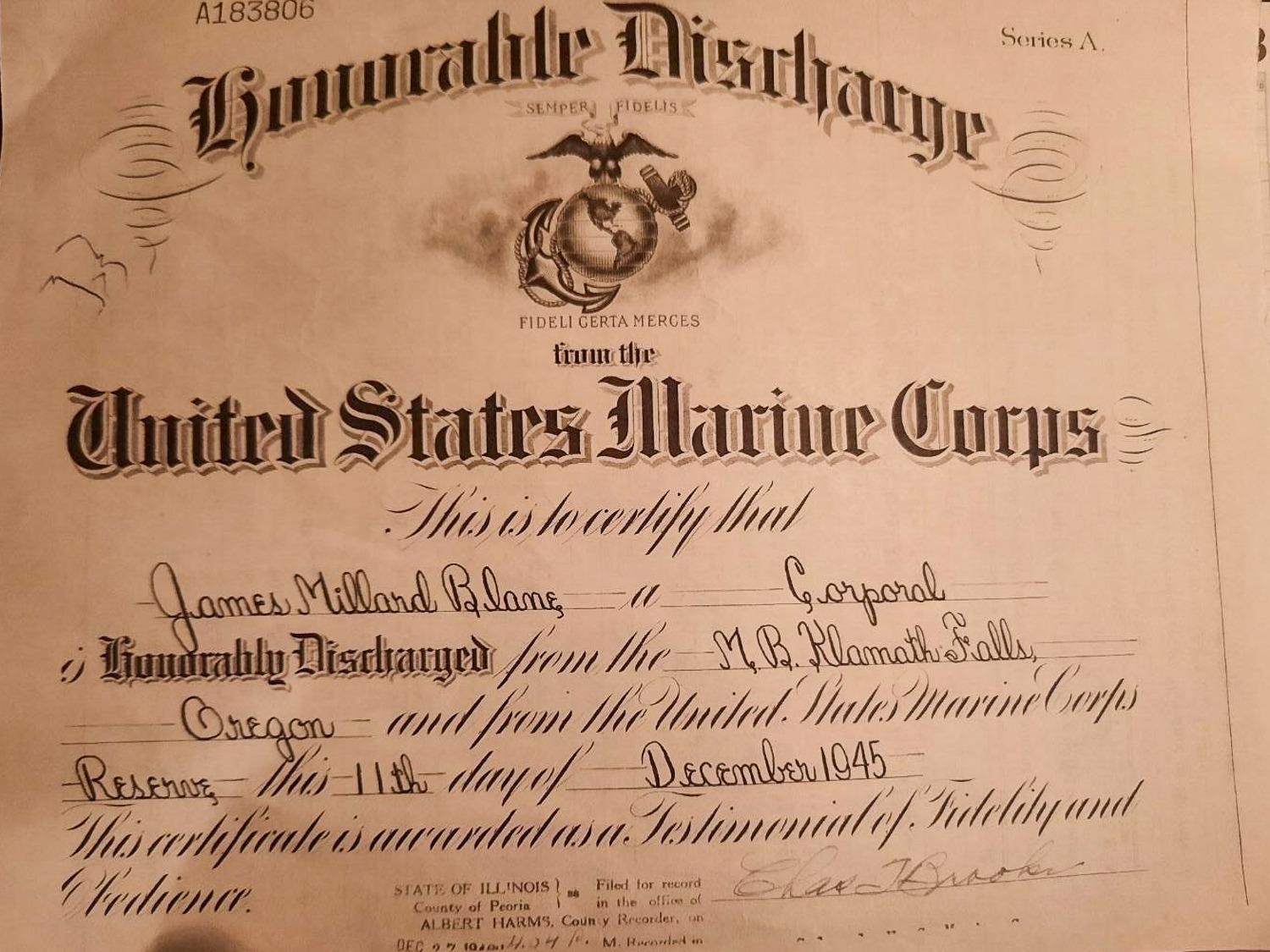

Tom JacksonThis photo, taken on Oct. 12, 2025, in Denver, Colo., shows a framed picture in Jim Blane’s apartment, highlighting the 4th Marine Division, in which he served. The Division experienced heavy casualties in the Battle of Iwo Jima. Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteJim Blane’s military discharge papers.

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteJim Blane’s military discharge papers.

He was honorably discharged from the military on December 11, 1945.

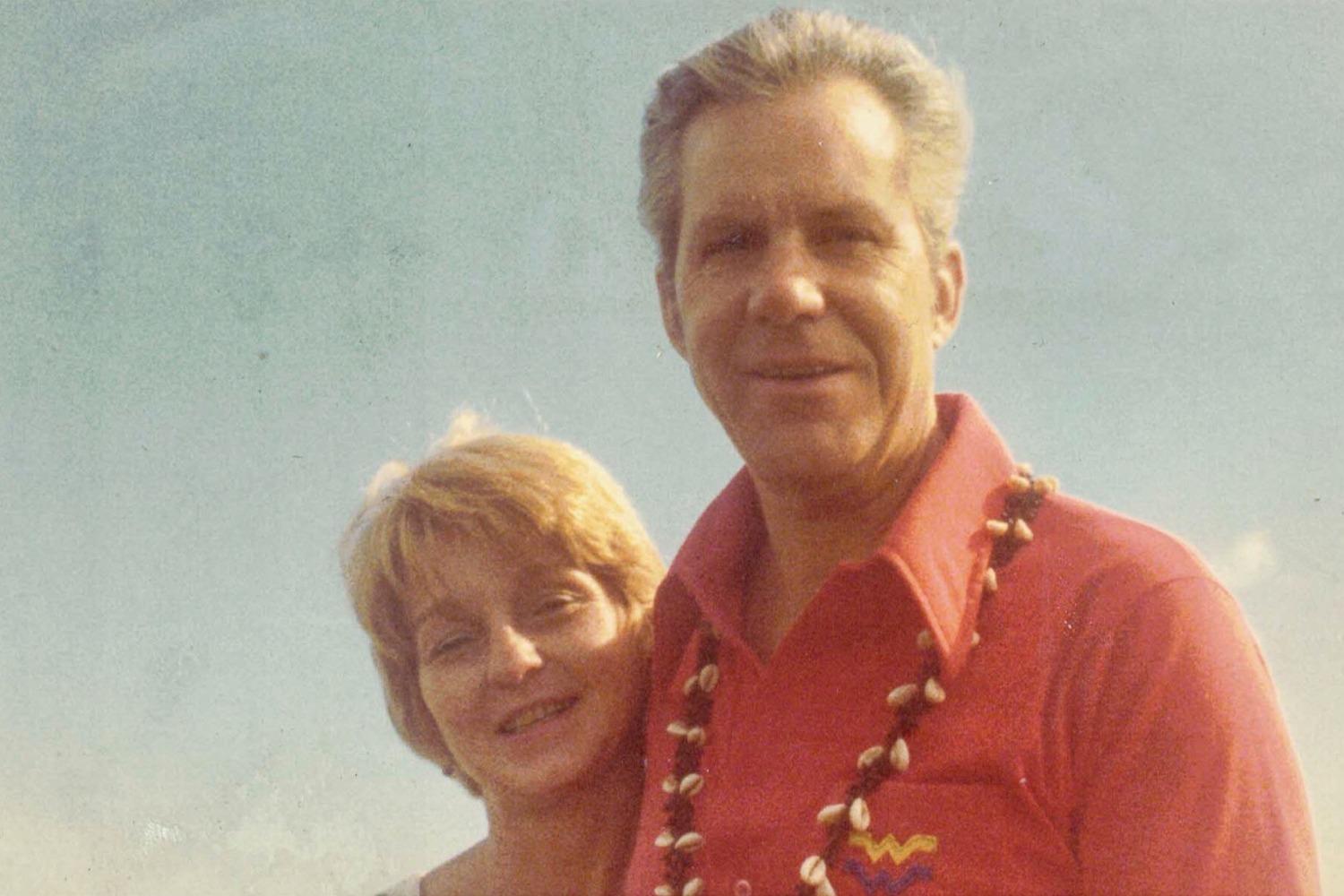

In the years that followed, Blane tried to forget everything he experienced in the war. He went back to Peoria and attended Bradley University, using the GI bill. He met his wife Nancy, an airline stewardess, on a blind date.

They were married for 60 years before Nancy passed away in 2017. He calls her his “only sweetheart that I truly loved.”

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteNancy and Jim Blane in Maui, Hawaii, in 1975. They were visiting the place where he went to Marine training.

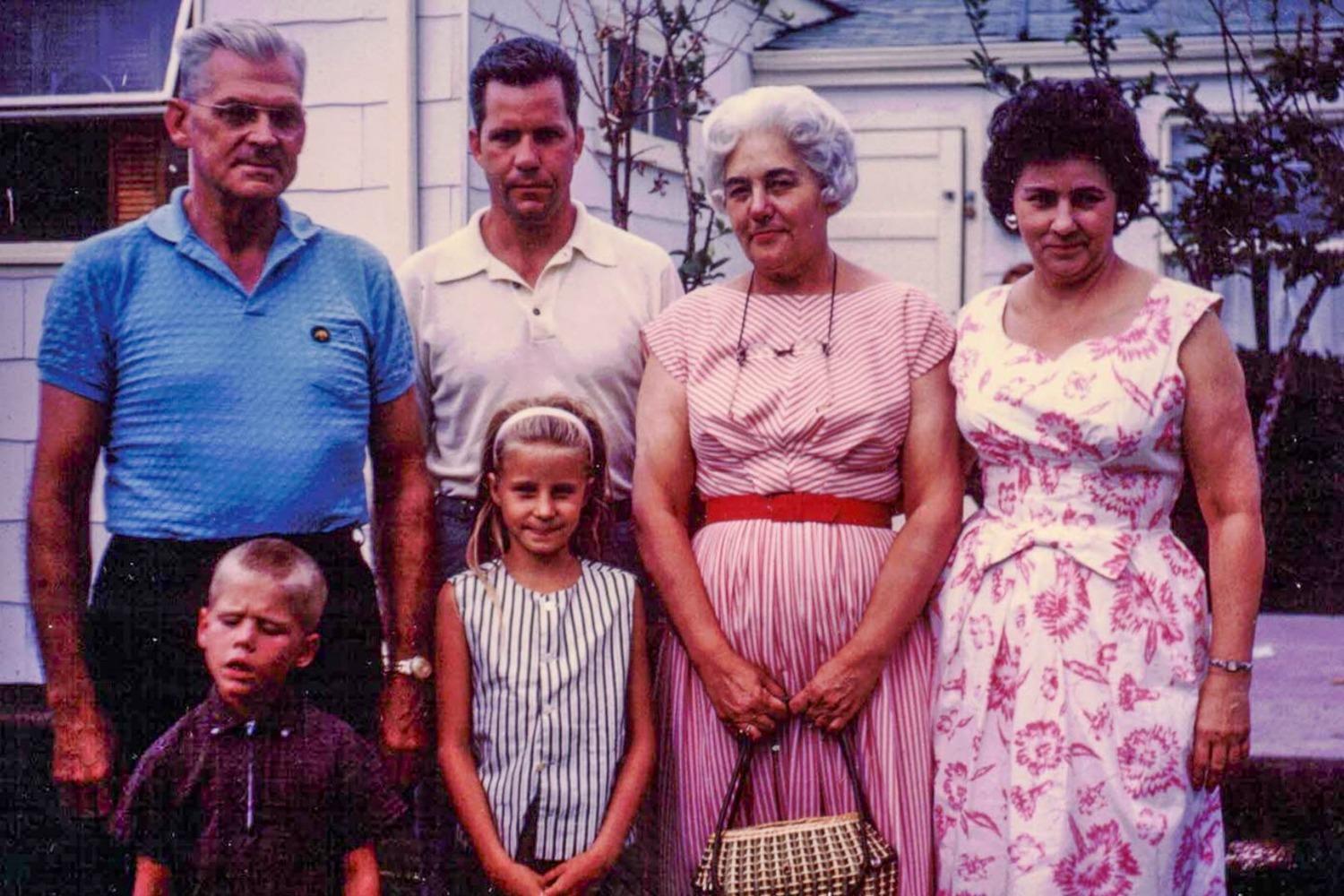

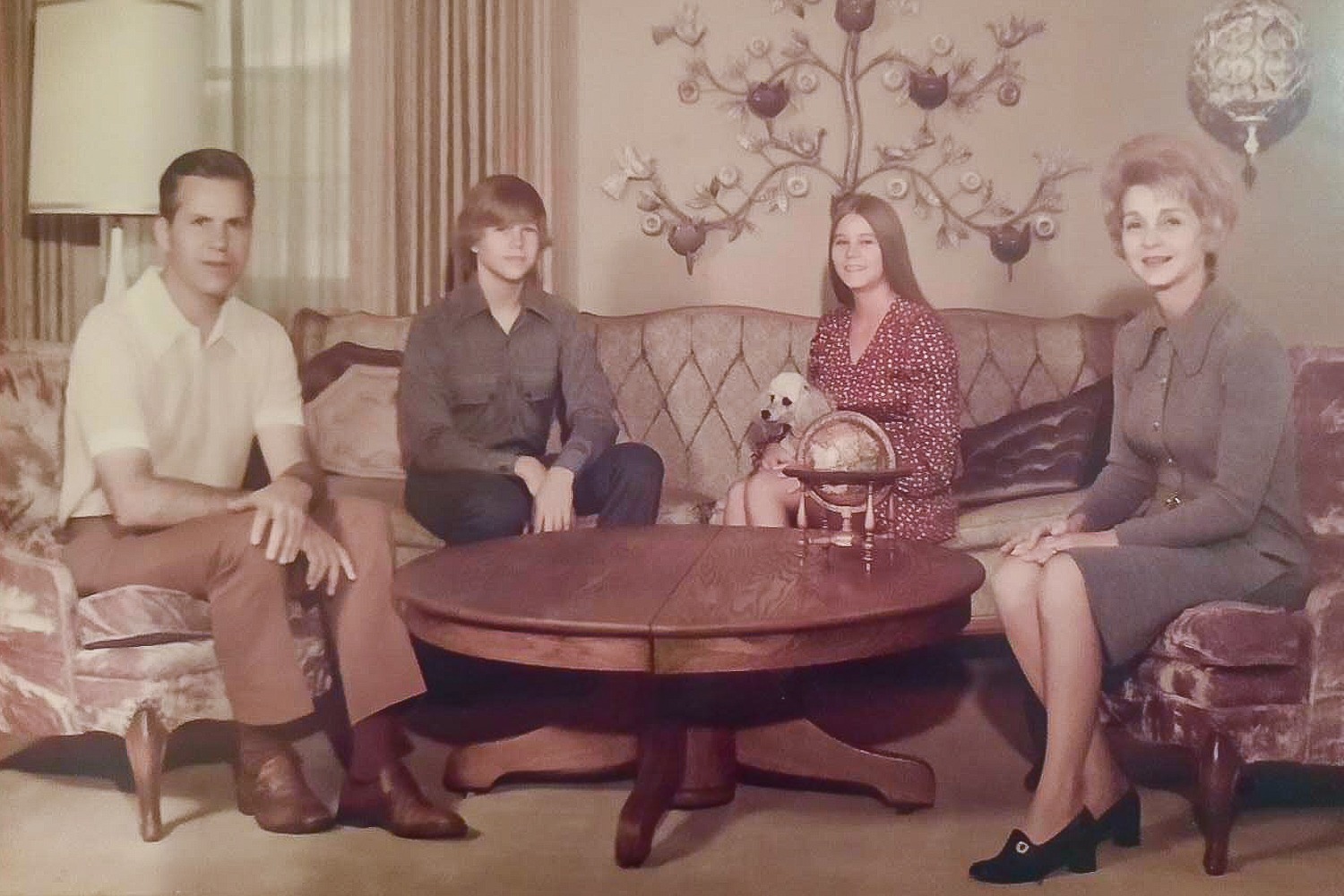

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteNancy and Jim Blane in Maui, Hawaii, in 1975. They were visiting the place where he went to Marine training.  Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteFrom left to right: Millard Blane (Jim’s father), Jim Blane, Pauline Smith (Jim’s mother-in-law) and Gladys Blane (Jim’s mother) and his children, Phil Blane and Jaime Blane, in 1964 in Illinois.

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteFrom left to right: Millard Blane (Jim’s father), Jim Blane, Pauline Smith (Jim’s mother-in-law) and Gladys Blane (Jim’s mother) and his children, Phil Blane and Jaime Blane, in 1964 in Illinois.

Together, the couple raised two children. Phil Blane said, growing up, his dad never talked about the war. He and his older sister Jaime knew not to bring it up. Blane acknowledges now that he was dealing with untreated PTSD.

“I would choke up. I couldn’t, couldn’t do it. And I didn’t want to act like an idiot. So I avoided it,” he said.

This long silence was not uncommon for World War II veterans, for many reasons, including the trauma they experienced.

“What we saw was a lot of World War II veterans — didn’t matter where they served, the Pacific Theater, European Theater, China, Burma, India — a lot of them just simply didn’t open up at all,” said Joey Balfour, assistant director of oral history at the National WWII Museum in New Orleans.

According to Balfour, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, popular films like “Saving Private Ryan” and “Band of Brothers” helped break through that reserve, convincing veterans that people really would want to hear their stories.

“I think a lot of them thought that they didn’t do anything spectacular and that nobody was going to be interested in what they had to say. But once they did start opening up, it was like a tidal wave,” said Balfour.

Jim Blane, Phil Blane, Jaime Blane and dog Gigi, and Nancy Blane at their home in Denver, Colo., in 1971.

Jim Blane, Phil Blane, Jaime Blane and dog Gigi, and Nancy Blane at their home in Denver, Colo., in 1971.

For Blane, much of that opening up has happened in the last 20 or so years, after he got involved with the Greatest Generations Foundation, a nonprofit that helps veterans revisit the places where they served, to try to foster a sense of belonging and connection and to heal.

Being around other veterans helped him talk about his wartime experiences with his children.

“I think for the sake of history, they started talking about it, and he saw that his buddies were also talking about it. And it became a little therapeutic to kind of get it out and talk it through,” said Phil.

“He told me some of the things that caused that PTSD. It’s some real, ‘oh my God’ kind of stuff,” Phil said. “When someone has PTSD, it may be from a car wreck or some horrible thing, a shooting. So it’s a one-time thing that happens. But he saw like 30 or 40 of these shocking kinds of things that stick with you forever.”

“So now I get it … and other veterans too, they clam up.”

Photo: Jim Blane on a trip with the non-profit the Greatest Generations Foundation to visit a graveyard in France.

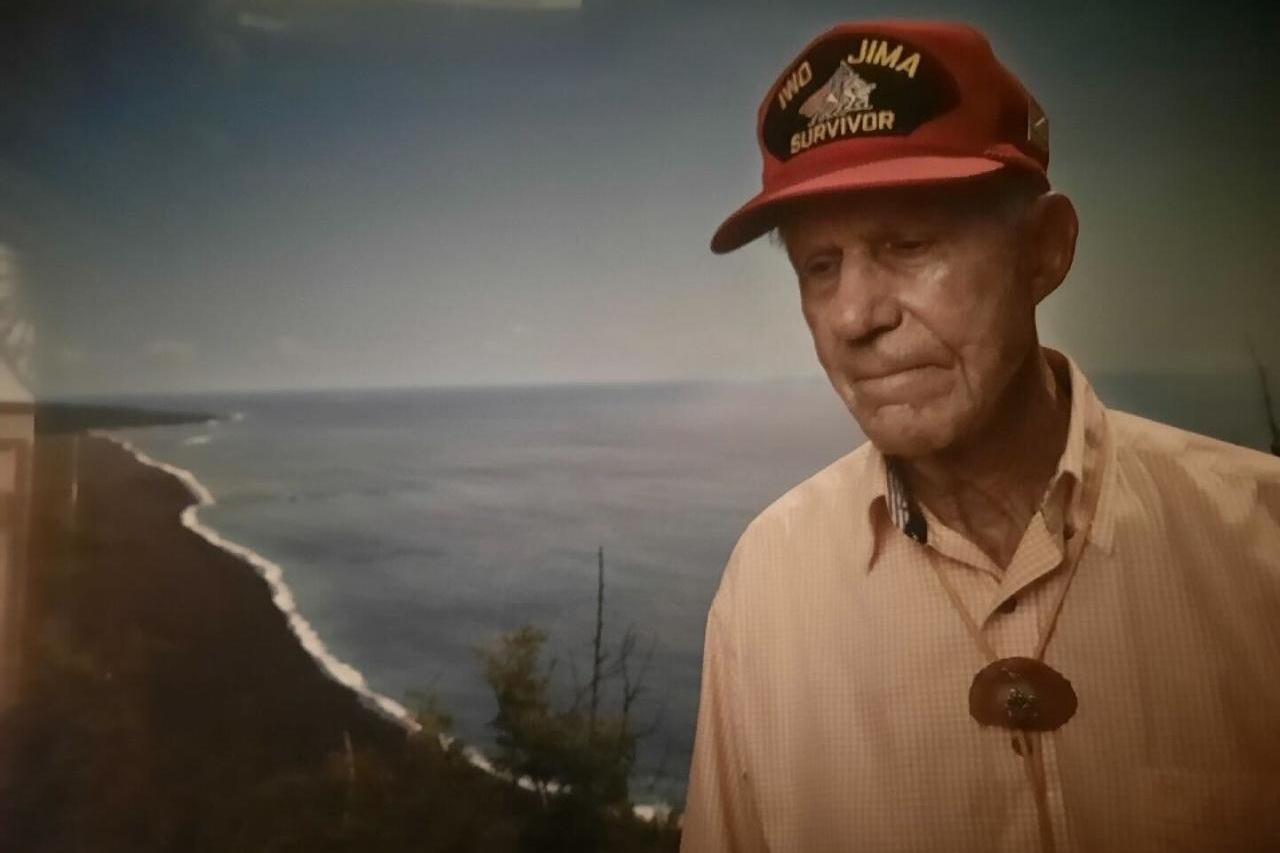

Ten years ago, Blane returned to Iwo Jima for the 70th anniversary of the battle. The ceremony brought together Japanese and American veterans to highlight the successful reconciliation and strong partnership between the two countries.

He said he had some bad feelings about the journey before he arrived, but the visit went well.

Blane has also visited Tokyo — and was surprised by the kind reception he received from the country he’d fought in the war.

“They treated me very nice. I didn’t think they would, but they did.”

Photo provided by Jim Blane’s familyJim Blane stands atop Mount Suribachi on the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Iwo Jima in 2015. He was there for a ceremony to bring together American and Japanese veterans.

Photo provided by Jim Blane’s familyJim Blane stands atop Mount Suribachi on the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Iwo Jima in 2015. He was there for a ceremony to bring together American and Japanese veterans.

Over the decades, Blane kept in touch with many of the Marines he served with — but each year, there are fewer and fewer.

“Well, most of them are gone,” he said, before asking his son who’s still living. Phil couldn’t think of anyone.

“Remember Arthur Godfrey?” Phil asked. “He was one in your foxhole. You were friends with him for years. And Don Whipple, he was 99. He just died.”

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteF-14 Tomcats conduct a flyby of the Iwo Jima memorial on Mt. Suribachi, January 16, 2003.

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteF-14 Tomcats conduct a flyby of the Iwo Jima memorial on Mt. Suribachi, January 16, 2003. Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteMt. Suribachi and Iwo Jima.

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteMt. Suribachi and Iwo Jima.

Eventually, there won’t be anyone left to tell firsthand what happened on Iwo Jima; it’ll only be preserved in history books and museums.

“We were able to record so many of these stories and experiences, and it’s truly unfortunate that we are nearing the end of that right now,” said Balfour. The National WWII Museum has collected a little over 12,000 personal narratives, ranging from oral history interviews to handwritten memoirs scribbled on paper. About a third of them are from the Pacific theater.

“It has really been, not just a pleasure, but an honor to be able to preserve these stories. Once these voices are gone, they’re gone. We don’t get a do-over,” said Balfour.

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteThe Marines Memorial near Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Va. The memorial was dedicated in 1954 to all Marines who have given their lives in defense of the United States since 1775.

Kevin J. Beaty/DenveriteThe Marines Memorial near Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Va. The memorial was dedicated in 1954 to all Marines who have given their lives in defense of the United States since 1775.

At the end of our interview, I tried to thank Blane for his service, but he was quick to offer a correction.

“You’re supposed to say, ‘thank you for my freedom.’ Say that.”

I repeated it back to him, “Thank you for my freedom.”

“There it is.”