Executive Summary

The Trump Administration announced agreements with Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk that pair price cuts on GLP-1 medicines with a federal push to broaden access, lowering Medicare prices paid by American seniors and invigorating the TrumpRx direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical channel.

The estimated federal Part D outlay for the injectable GLP-1 products (assuming Medicare’s typical subsidy share) is between $855–$1,743 per new user, per year; thus, every 1 million new users would cost Medicare about $1.74 billion annually (or $0.89 billion at starter-dose pricing).

The administration’s announcement represents a consequential policy shift on access to anti-obesity therapies, set from the Oval Office rather than through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ usual benefit and formulary processes.

Introduction

The Trump Administration recently announced agreements with Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk that pair price cuts on GLP-1 medicines with a federal push to broaden access, lowering Medicare prices paid by American seniors and invigorating the TrumpRx direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical channel.

For Medicare and Medicaid, the White House quoted a $245 price per 30-day supply for currently marketed injectables (e.g., Wegovy, Zepbound), with Medicare beneficiary copays capped at $50. Cash-pay prices will be offered through the TrumpRx channel, starting at around $350 and expected to incrementally fall to about $245 over two years. Starter doses of forthcoming oral GLP-1s are slated to begin at a product-dependent $149 or $150 if approved. Using these prices, the estimated federal Part D outlay for the injectable GLP-1 products (assuming Medicare’s typical subsidy share) is between $855–$1,743 per new user, per year. Coverage and pricing changes will phase in during 2026, with cash prices as early as January, Medicare access by mid-year, and Medicaid timing varying by state participation. The package also includes industrial commitments and limited tariff relief for the drug companies.

While this deal applies only to medications purchased through Medicare and Medicaid, this announcement represents a consequential policy shift on access to anti-obesity therapies. These new terms amount to an administrative end-run around normal coverage determinations – set from the Oval Office rather than through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) usual benefit and formulary processes. Instead of plan-by-plan formulary decisions vetted by expert committees and aligned with the annual bid cycle, the White House set prices and promised a uniform $50 Medicare copay through an executive package and a time-limited demonstration. This method shifts decisions from decentralized plan sponsors to centralized federal bargaining. The result is faster near-term access, yet potentially less predictable, model-dependent coverage. Costs, utilization management, and participation will hinge on administrative design rather than established notice-and-comment processes.

Standard Medicare Coverage Determinations

To understand why the process matters in the GLP-1 coverage determination, let’s first examine the traditional method for formulary inclusion. Part D is decentralized and formulary driven. Each Part D sponsor builds a formulary that is developed and maintained by an independent Pharmacy & Therapeutics (P&T) committee. CMS sets structural guardrails and reviews formularies annually, but plans decide tier placement, utilization management (UM), and preferred products within those guardrails. By regulation, formularies must include at least two distinct drugs in each category and class, with additional, stricter expectations for certain clinically sensitive areas (the “six protected classes,” described below). P&T committees must have a majority of practicing physicians and/or pharmacists and meet regularly, with decisions documented in writing.

Part D plans must generally cover “all or substantially all” drugs in six protected classes – antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, antiretrovirals, antineoplastics, and immunosuppressants for transplant – subject to limited exceptions. At the same time, statute and CMS guidance exclude certain categories from Part D altogether, including agents when used for anorexia, weight loss, or weight gain (historically the key barrier for anti-obesity indications), along with other exclusions like drugs for cosmetic purposes or fertility. CMS has recently discussed reinterpretations at the margin, but the long-standing framework remains the backdrop for plan decisions.

Within these rules, sponsors use tiering, preferred pharmacy networks, and UM tools (e.g., prior authorization, step therapy, quantity limits) to balance access, safety, and cost. CMS reviews formularies for adequacy and compliance (including protected-class treatment and transition processes for new enrollees) as part of the annual bid and contract cycle; changes are implemented through plan updates, not ad hoc national announcements. Beneficiaries who disagree with a plan decision can request a coverage determination and pursue a five-level appeals pathway (beginning with a plan redetermination and, if necessary, review by an Independent Review Entity or higher levels of review authority).

The Announcement: Policy and Implications

The new arrangements take a different route. Rather than coverage expanding through plan-by-plan formulary decisions following rulemaking or legislation, the administration announced headline prices and a uniform Medicare copay outside the customary actuarial and bidding cycle. Even supporters of the policy announcements emphasize that operational details are still emerging, underscoring the degree to which this approach sits alongside, rather than within, the standard Part D processes.

Several elements of the announcement therefore merit attention. First, pre-setting a $50 copay nationally is unusual for Part D, where cost-sharing is typically a function of plan design and formulary placement. Aligning such a copay with existing benefit tiers, mid-cycle, poses practical questions for plans whose 2026 bids assumed different unit costs and utilization. Second, the package includes non-coverage policy components – tariff relief and expedited regulatory incentives for forthcoming oral GLP-1s – which demonstrate that this is an integrated industrial-policy bargain rather than a conventional Medicare coverage determination. While such linkages may accelerate lower net prices and greater supply, they sit outside Medicare’s normal legal architecture, where Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, CMS coverage, and trade policy are meant to operate in distinct lanes.

The accessibility of coverage is a central tradeoff. A demonstration model can expand access more quickly than legislation, but it is inherently contingent on myriad factors. Participation by plan sponsors is voluntary, and states will make their own choices about Medicaid participation. Further, the scope of beneficiary eligibility, prior-authorization standards, and appeal rights will be set by model terms rather than by the durable, statute-centered frameworks that plans and beneficiaries typically rely on. Some reporting highlights unanswered questions about eligibility criteria, timelines, and how the promised $50 copay will be reconciled with existing plan designs. For beneficiaries, expectations shaped by national headlines may collide with variation across plans and model participation, at least in the near term.

There are also implications for competition and program spending. On the one hand, transparent posted prices and a uniform Medicare copay could reduce patient cost barriers and spur broader diffusion of medicines with meaningful cardiometabolic benefits. On the other, fixing price points with two incumbent manufacturers risks narrowing the role of plan-level negotiations and rebates that ordinarily discipline net prices, while creating precedent for bespoke agreements outside the competitive formulary process. Independent modeling done before this announcement suggests expanded Medicare coverage of GLP-1 therapies would materially increase federal outlays even under discounted prices – a reminder that long-run affordability is dependent on very specific criteria.

None of these considerations diminish the near-term access gains the administration is seeking. For many seniors, especially those with obesity and co-morbid conditions, a $50 copay is a meaningful reduction from current out-of-pocket costs, and the TrumpRx channel could offer relief to uninsured or under-insured patients who have relied on compounded products or paid high cash prices. But the mechanism matters, in part because it may create pressure to offer GLP-1s at lower prices to those covered by traditional private health insurance plans. By advancing coverage and pricing commitments through an executive-led package and a demonstration rather than through statute or the standard Part D formulary pathway, the policy makes access more sensitive to administrative design choices, manufacturer participation, and the outcome of future negotiations. That sensitivity is the source of today’s opportunity – and tomorrow’s uncertainty.

Initial Medicare Cost Scenarios

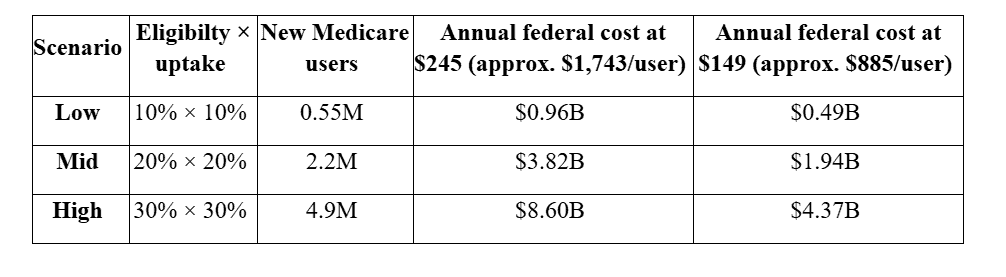

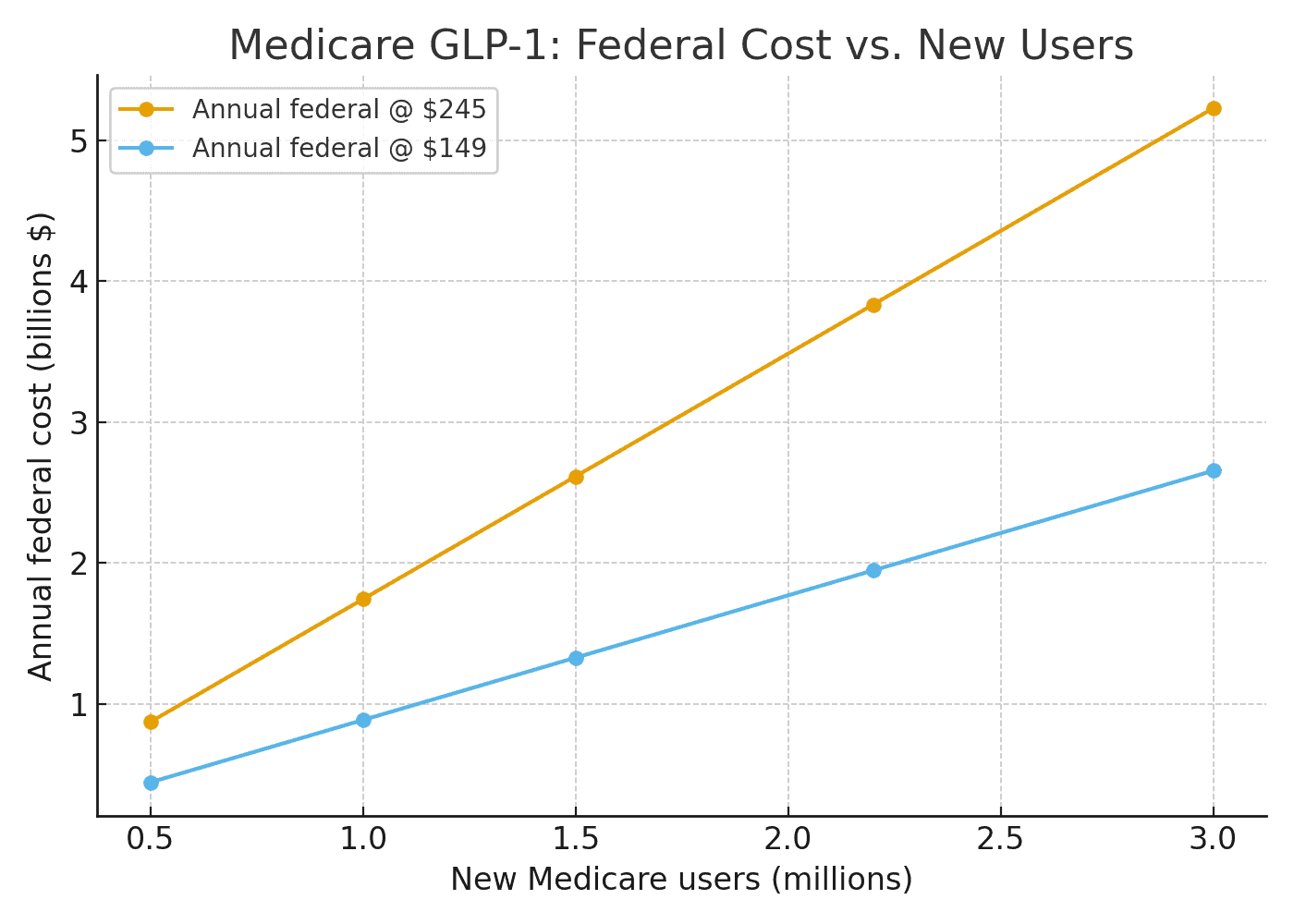

CMS has not released final eligibility or plan participation but observed Part D enrollment can help illustrate possible outcomes for some simple scenarios. Using the White House’s posted prices – $245 per 30-day fill (with a $50 Medicare copay) and $149 for certain starter doses – the implied federal Part D outlay is roughly $1,743 per new user per year at $245, and $885 per new user per year at $149, assuming Medicare’s typical subsidy share. That means every 1 million new Medicare users would add about $1.74 billion in Medicare costs annually (or $0.89 billion at starter-dose pricing). Under a mid-range scenario – say 2.2 million new users – the annual federal cost would be about $3.8 billion at the $245 price (roughly half that if implementation begins mid-year). This is reflected more specifically in the table below. The main variables include the eligible share of Part D enrollees and the projected uptake of those newly eligible. The points used are further outlined below:

Eligible share of Part D = 10 percent, 20 percent, 30 percent (reflecting a targeted pilot versus a broader high-risk cohort).

Uptake among eligible (within a year) = 10 percent, 20 percent, 30 percent (access expands, but not everyone initiates immediately).

The above computations use 54.8 million Part D enrollees, multiplied by the eligible share of patients and by the projected uptake for user counts, times the per-user-year federal costs derived above. It is important to note that these represent incremental federal drug outlays for new users driven by the obesity-coverage expansion – i.e., not net of any medical-care offsets and not including any savings (or added costs) on those who were already using GLP-1s for diabetes under existing coverage.

Early months may skew toward starter doses (closer to the $149 line), so near-term spending could be closer the rightmost column; as maintenance dosing normalizes, costs drift toward the $245 anchor. The deal is slated to begin mid-2026, so calendar year 2026 spending would be roughly half of the annualized figures above. Using the deal’s stated prices and Medicare’s typical subsidy share, each 1 million new users in Medicare implies about $1.74 billion per year in federal Part D spending at the $245 price (or $0.89 billion at the $149 starter price).

Looking Forward

While there is little ambiguity about the goal of the announcement, several outstanding questions remain. The announcement’s accompanying White House fact sheet, as well as corporate press releases, left out certain key details important to ensuring transparent, patient-centered implementation (the professed goal of this entire endeavor). What to watch next: (1) the formal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation model announcement detailing eligibility, utilization-management standards, and how the $50 copay interfaces with Part D benefit tiers; (2) actual plan participation rates and whether CMS offers risk-adjustment or reconciliation guardrails to account for mid-cycle changes; (3) whether Congress codifies, revises, or limits Medicare’s authority to cover anti-obesity medications; (4) the response from other manufacturers as orals and next-generation agents approach approval, now that regulatory changes and price anchors are in play; and (5) whether or not this dovetails with or supplants the Inflation Reduction Act price-setting mechanisms. These factors, however, will determine whether the initiative ultimately strengthens predictable and dependable access within Medicare.

Conclusion

Medicare’s default is decentralized, rules-based, and indication-specific – not White House-brokered global coverage. Part D is decentralized and formulary driven. Each Part D sponsor builds a formulary that is developed and maintained by expert panels. CMS sets structural guardrails and reviews formularies annually, but plans decide tier placement, UM, and preferred products within those guardrails. Rather than coverage expanding through plan-by-plan formulary decisions following rulemaking or legislation, however, the administration announced headline prices and a uniform Medicare copay outside the customary actuarial and bidding cycle. By advancing coverage and pricing commitments through an executive-led package and a demonstration rather than through statute or the standard Part D formulary pathway, the policy makes access more sensitive to administrative design choices, manufacturer participation, and the outcome of future negotiations. Based on the particulars of implementation, there is still ambiguity if this is a true shift in access or if it is another flashy deal at the expense of American patients.