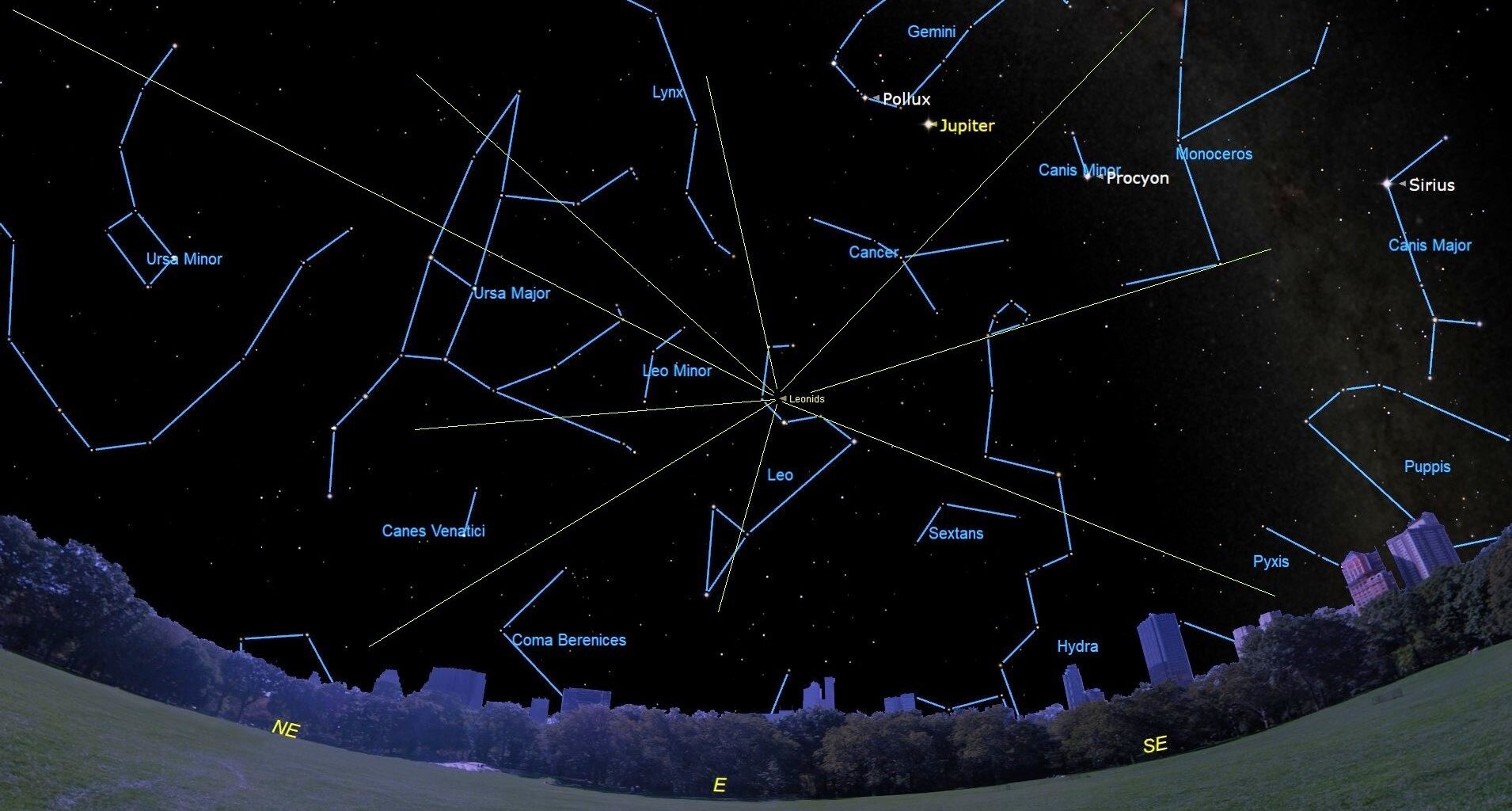

Probably the most famous of the annual meteor showers will soon be reaching its maximum: The Leonids. These ultrafast meteors are expected to be at their best for North American on Tuesday morning (Nov. 18).

The Leonid meteor shower are known for producing some of the most amazing meteor displays in the annals of astronomy. Most notable are meteor storms such as in 1799, 1833 and 1966 when meteor rates of tens of thousands per hour were observed. More recently, in 1999, 2001 and 2002, lesser Leonid displays of up “only” a few thousand meteors per hour took place.

You may like

Comet crumbs

The Leonids received their moniker because the shower’s emanation point — from where the meteors seem to fan out — is located within the constellation of Leo, the Lion, from within the backward question mark pattern of stars known as “The Sickle.” The meteors are caused by periodic comet Tempel-Tuttle, which sweeps through the inner solar system every 33⅓ years. Each time the comet passes closest to the sun it leaves a “river of rubble” in its wake; a dense trail of dusty debris. A meteor storm becomes possible only if the Earth were to score a direct hit on a fresh dust trail ejected by the comet over the past couple of centuries.

The “lion’s share” (no pun intended) of comet dust can be found just ahead and trailing behind Tempel-Tuttle. That comet last swept through the inner solar system in 1998. That’s why spectacular meteor showers were seen in 1999, 2001 and 2002, with declining numbers thereafter.

In 2016 Tempel-Tuttle reached aphelion, that point in its orbit, as far from the sun as it can get: 1.84 billion miles (2.96 billion km). Now the comet is on its way back toward the sun and inner solar system and will sweep closest to the sun again in May 2031.

Slim pickings in 2025

But it’s also, in the general vicinity of the comet where the heaviest concentrations of meteoroids are as well. In contrast, at the point in the comet’s orbit where we will be passing by on Tuesday morning, there’s only a scattering of particles; bits of comet debris that crumbled off the comet’s frozen nucleus perhaps a millennia or two ago.

So, the 2025 Leonids are expected to show only low activity this year. According to a highly regarded Russian expert in meteor shower predictions, Mikhail Maslov, his forecasts indicate peak Leonid activity of approximately 15 meteors per hour during the time frame from 18:00 UT on Nov.17 to 00:00 UT on Nov. 18. That interval would favor central and eastern Asia, including Japan.

During that same interval, Maslov is also suggesting an interaction with a trail of meteoroids expelled by comet Tempel-Tuttle in 1699. Maslov cautions that many of these tiny particles will likely be blown away by solar radiation pressure. “However,” he adds, “Some larger particles still could be present so the number of bright meteors could increase during the period from 18 to 23 hours UT.”

Again, this timeframe favors central and eastern Asia.

You may like

For North America, the best time to look will be before dawn on Tuesday, Nov. 18. By then, the Leonids will be past their peak intensity, and will probably not produce more than 5 to 10 meteors per hour.

The moon — just a narrow crescent — is just a couple of days from new and will pose no interference whatsoever. But be mindful that Leonids are expected to dart across your line of sight on an average of once every 6 to 12 minutes. And that’s only assuming you have a wide-open view of the entire sky and are blessed with dark, non-light polluted conditions.

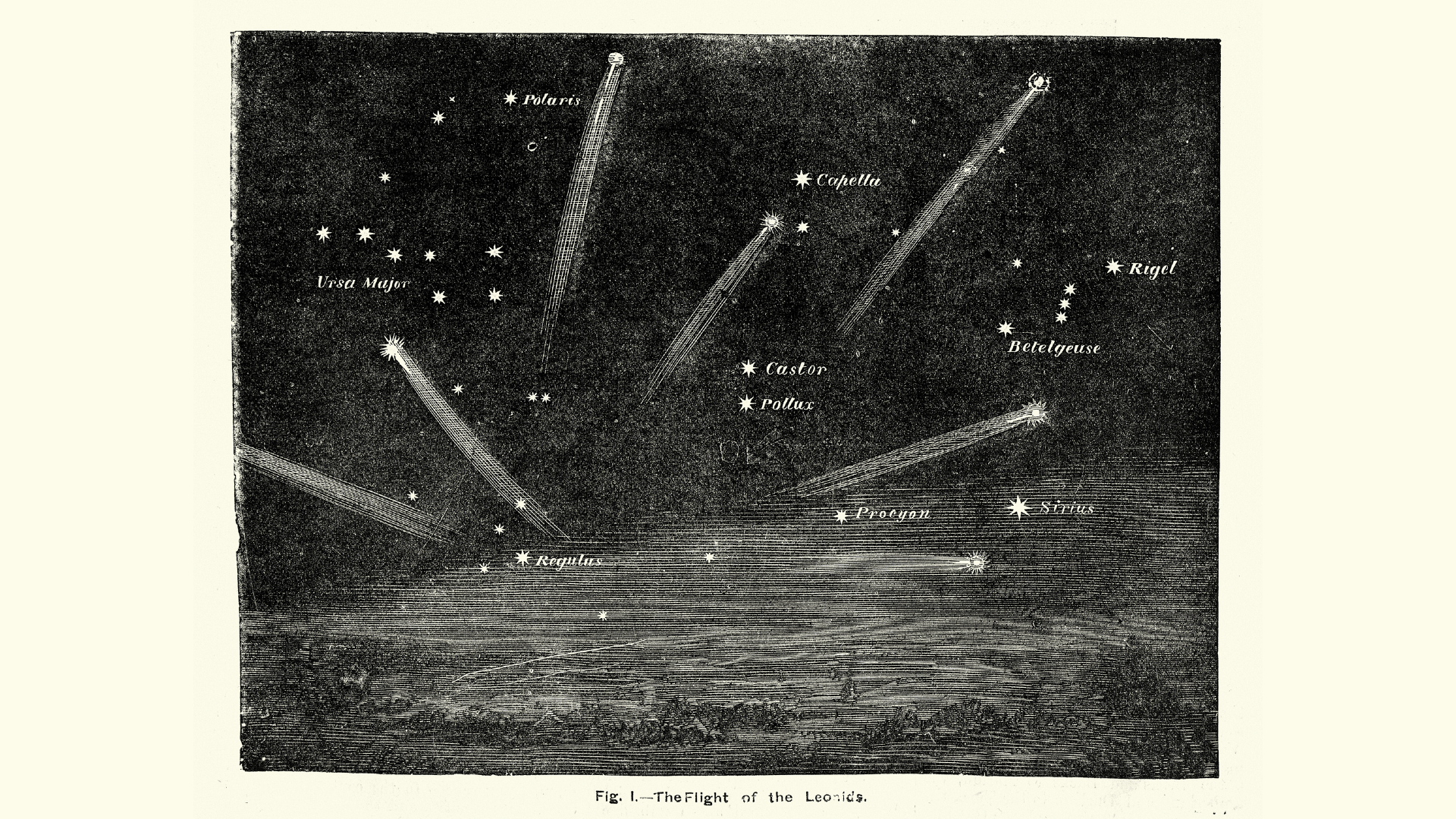

An astronomy chart from 1883 depicting the Leonids meteor shower. (Image credit: duncan1890/Getty Images)How to observe and what to look for

Watching a meteor shower is a relatively straightforward pursuit. It consists of lying back, looking up at the sky and waiting. Keep in mind that any local light pollution or obstructions like tall trees or buildings will further reduce your chances of making a meteor sighting.

BEST CAMERAS FOR ASTROPHOTOGRAPHY

(Image credit: Nikon)

If you’re looking for a good camera for meteor showers and astrophotography, our top pick is the Nikon D850.

Leo does not start coming fully into view until the after-midnight hours, so that would be the best time to concentrate on looking for Leonids. As dawn is about to break at around 5 a.m. local time, The Sickle will have climbed more than two-thirds of the way up from the southeast horizon to the point directly overhead (called the zenith).

Also, because the Leonids are moving along in their orbit around the sun in a direction opposite to that of Earth, they slam into our atmosphere nearly head-on, resulting in the fastest meteor velocities possible: 45 miles (72 km) per second. Such speeds tend to produce bright meteors, which leave long-lasting streaks or vapor trains in their wake.

A mighty Leonid fireball can be quite spectacular, but such outstandingly bright meteors are likely to be very few and very far between this year (if any are seen at all).

A look ahead

The good news is that as Comet Tempel-Tuttle draws closer to the sun, the Leonids are expected to slowly improve. But the very best years of the next Leonid cycle won’t come until 2034 and 2035, when hourly rates in the many hundreds per hour may be possible.

But if you can’t wait until then, here’s some good news: A far more prolific meteor shower is coming our way in less than a month: the December Geminids, now considered to be the best meteor shower of the year, producing over 100 per hour. They are expected to peak during the overnight hours of Dec. 13-14. Space.com of course, will provide you with all the details as we get closer to that date. So, stay tuned!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky and Telescope and other publications.