Overview:

Upper Valley photographer Jack Rowell’s book, “Jack Rowell: Photographs,” will be published this month. The publication is a culmination of his life’s work, photographing mostly in the Upper Valley. Rowell’s book is a record of his community and how he sees it, and his camera is his way of relating to the world. The book includes portraits of people he likes, his friends, and photographs he took during his drinking years in the 1970s and ’80s. Rowell’s book is also a monument to his time, when Vermont, and the world, were wilder places.

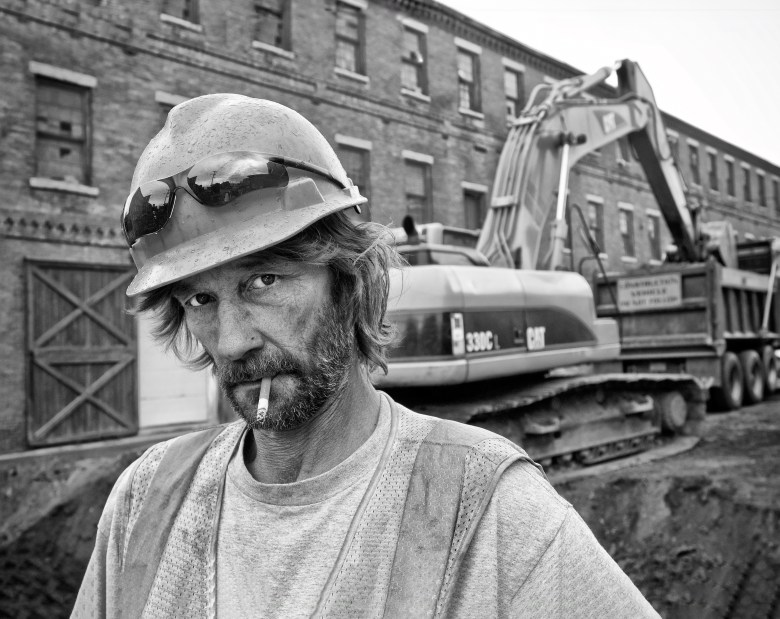

A construction worker in Claremont, N.H., in 2007. (Jack Rowell photograph)

A construction worker in Claremont, N.H., in 2007. (Jack Rowell photograph)

Leafing through the photographs in his forthcoming book is a walk back in time for Jack Rowell. The book was still at the printer’s during a recent interview, but he unrolled sheets of proofs on a table in Randolph’s White River Craft Center.

As he turned the pages, he talked about the people whose portraits he’s taken, people he likes, his friends. He talked about the Tunbridge Fair, his first serious subject, and photographs he took during his drinking years, the 1970s and ’80s, when Vermont, and the world, were wilder places.

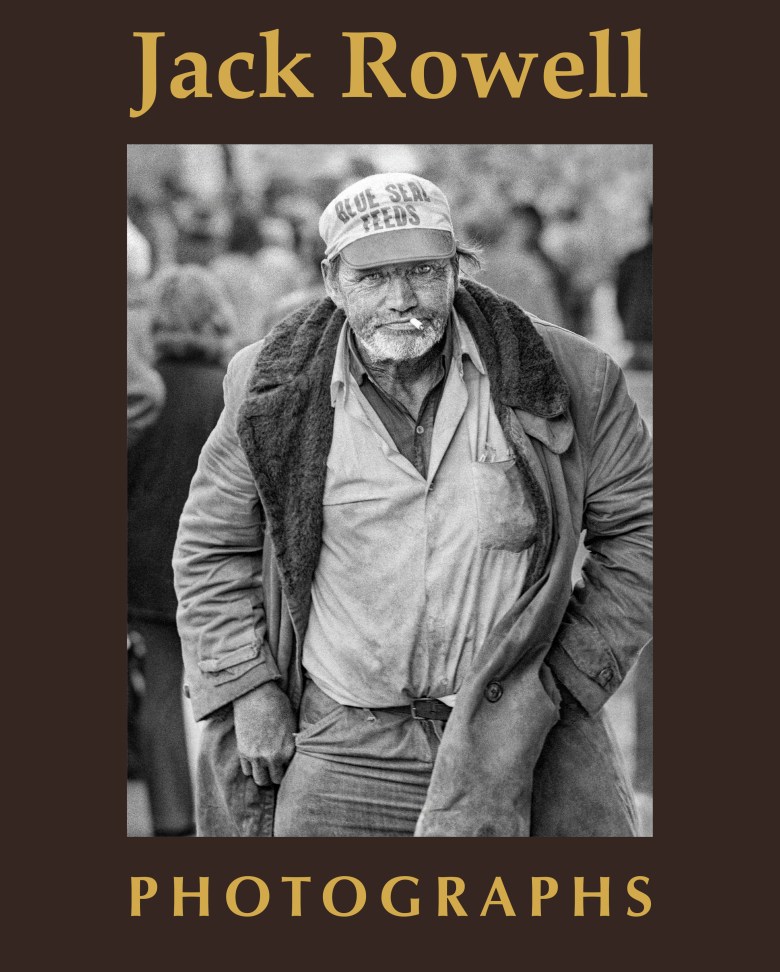

“Jack Rowell: Photographs” to be published Nov.22, 2025.

“Jack Rowell: Photographs” to be published Nov.22, 2025.

“It’s pretty much my life that I’ve photographed since I was a teenager,” Rowell said.

Yes, but there’s something more going on in “Jack Rowell: Photographs,” which is due out at a launch party on Nov. 22 at the craft center. Rowell, a Central Vermont native who is, as many photographers are, by turns gregarious and owlish, has photographed mostly in the same place for much of his life. His book is also a record of his community and how he sees it.

“His camera is his way of relating to the world, but it’s not superficial. It’s a real attachment,” Sara Tucker, a Randolph native who’s bringing Rowell’s book out through Korongo Books, the small publishing company she runs with her husband, Patrick Texier, said in a phone interview. “You become his subject, and you become his friend.”

The book is a kind of culmination, a monument to Rowell’s career, and also to his time, when the Vermont he was born into more or less vanished.

Photographer Jack Rowell. (Courtesy Jack Rowell)

Photographer Jack Rowell. (Courtesy Jack Rowell)

Rowell, a fifth-generation Vermonter and longtime Randolph resident, considers himself a Tunbridge native. His parents split up in 1960, when he was 5. His father, a fun-loving, but hard-working woodsman who operated Tunbridge Tables, selling rustic furniture he made himself, moved to Groton, Vt., just north of Orange County. His mother, a devout evangelical Christian, moved to Randolph. Rowell went with his dad, his sister, Janet, with mom, though Jack spent weekends with his mother, attending church and joining a youth group.

The artistic impulse hit him early on. “I remember the first time I got in big trouble,” he said. He was 5 or 6 years old. “I was drawing a fish on the wall, under a table. I caught hell for that.”

His father took him hunting and fishing, and the outdoors were a constant. When he was a young child, his mother would carry him around to the deer heads mounted on the wall so he could pat their fur before bedtime.

Rowell was a good student, until he was assigned homework, which got snared on his undiagnosed dyslexia. He found a refuge in science and the arts, and bailed out of the Groton schools, which had little of either, in favor of Randolph’s then-new junior high.

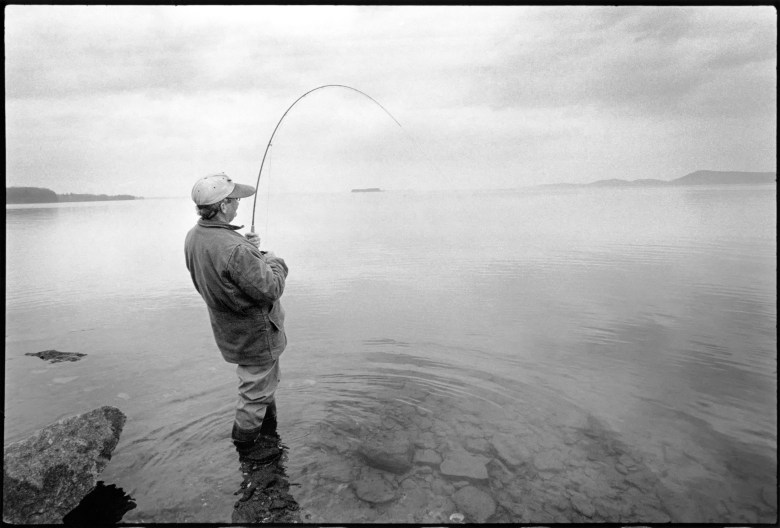

“Fish On: The Inland Sea” taken in 1994, from the upcoming book “Jack Rowell: Photographs.” (Jack Rowell photograph)

“Fish On: The Inland Sea” taken in 1994, from the upcoming book “Jack Rowell: Photographs.” (Jack Rowell photograph)

Though he continued to draw and paint, he never liked how his attempts came out. Photography came to him in the form of a Kodak Instamatic he got as a present, then a more advanced camera loaned to him by a family friend who’d brought it back from service in Vietnam. His eighth grade science teacher, John Lackard, showed him how to develop film and make prints. Photography provided the artistic revelation he needed.

Tucker, who was a year ahead of Rowell in school, remembers him as “a bit shy and awkward. But he was interesting,” because he carried a camera everywhere. “He was the only kid I knew who was serious about work,” she said.

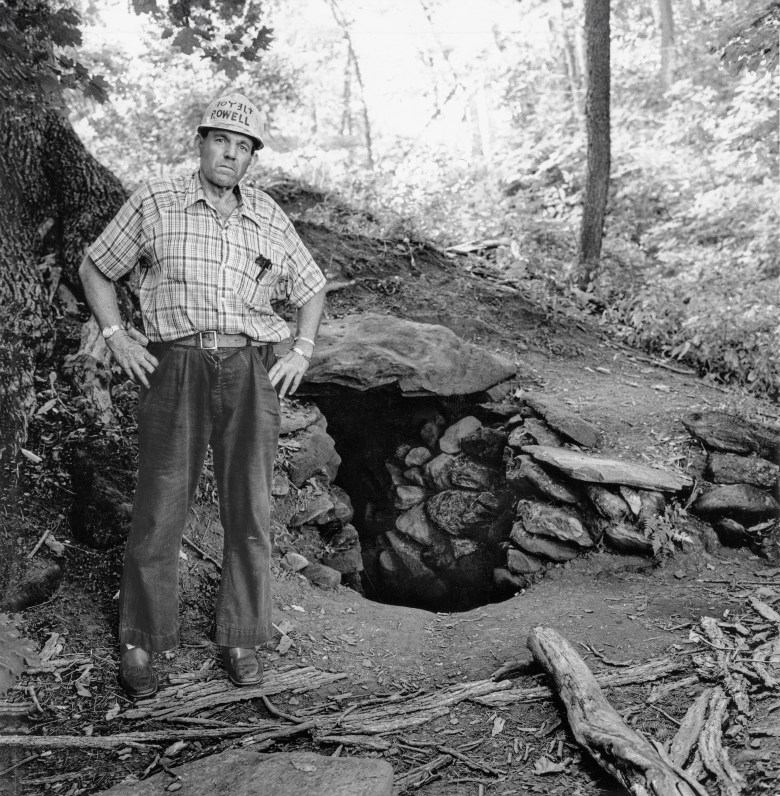

Jack Rowell’s father John C. Rowell in an undated photograph. (Jack Rowell photograph)

Jack Rowell’s father John C. Rowell in an undated photograph. (Jack Rowell photograph)

He took photos for The Herald of Randolph (now the White River Valley Herald) and when he ended up a few credits short of what he needed to graduate high school, he embarked on a career in photography.

He had gotten a head start, just by photographing life around him. The most vibrant scene in Orange County was the annual World’s Fair in Tunbridge.

To say it was a different time doesn’t quite do the photos justice. In one, a man in the fair’s notorious beer hall brandishes a knife as he looks at the camera. In the next image, he’s pointing a handgun at the young photographer.

Those photographs are from 1983, but Rowell took the fair as a subject much earlier. The Herald of Randolph published a book of Rowell’s work, “Tunbridge Fair,” in 1980, when Rowell was in his mid-20s.

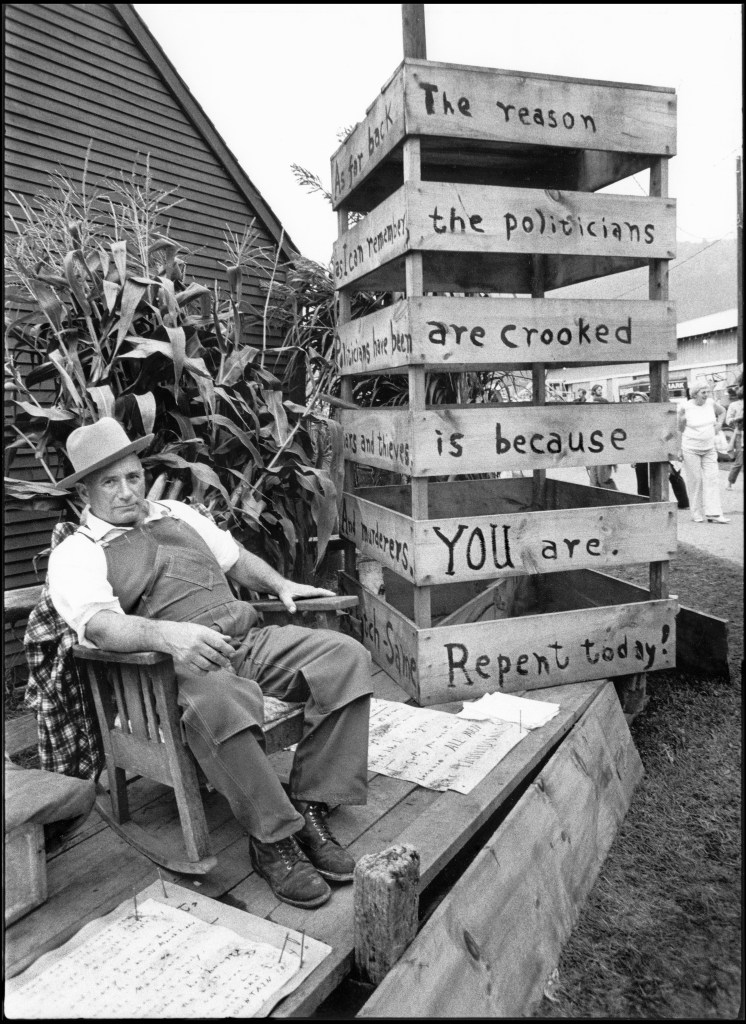

Grant Corwin at the Tunbridge Fair, circa 1976. (Jack Rowell photograph)

Grant Corwin at the Tunbridge Fair, circa 1976. (Jack Rowell photograph)

He seemed on his way toward his life’s work, but he had another occupation as a part-time drinker. As the writer Raymond Carver said, “Booze takes a lot of time and effort if you’re going to do a good job with it.”

Drinking shows up in “Jack Rowell: Photographs,” too. There are a couple of photographs he took at the Villanova, a long-defunct bar in Randolph, “a place I used to drink at a lot,” Rowell said. “It had a bad reputation, but it was nowhere near as bad as people made out that it was.”

Miaja Bradley at the Vermont History Expo in Tunbridge, Vt., in 2010. (Jack Rowell photograph)

Miaja Bradley at the Vermont History Expo in Tunbridge, Vt., in 2010. (Jack Rowell photograph)

In another photograph, taken July 4, 1983 in Warren, Vt., a young woman sports a T-shirt that reads “Decadence: a way of life.” She let Rowell pour his beer down the front of the shirt, with predictable results. “I was probably shit-faced when I took it,” he said.

In a foreword to the book, Chris Jackson, a longtime friend of Rowell’s illuminates this chapter, pointing out that it’s hard to be a freelance photographer in Vermont if your driver’s license is taken away. Rowell took steps to get sober in 1993, Jackson wrote.

Though he put it behind him, Rowell still owns it. “I don’t regret anything I did,” he said.

Rowell did all kinds of photography to make ends meet. He photographed stoves and other products for Vermont Castings. He took family portraits and shot weddings. He has been a regular in the pages of Image, the Upper Valley-based magazine.

He’s become known as an exacting photographer of great technical skill, particularly with studio and on-camera lighting. Part of the reason his portrait subjects look so vital is due to how flawlessly they are illuminated.

“He really opened my eyes to the technical side of photography,” Myra Hudson, a Royalton-based photographer who has assisted Rowell, said. “He’s pretty snobby about it. He’s excruciatingly good at lighting.”

Thelma Follensbee, taken in Lebanon, N.H., in 2012. (Jack Rowell photograph)

Thelma Follensbee, taken in Lebanon, N.H., in 2012. (Jack Rowell photograph)

Some of the commercial work was done in tandem with his sister, Janet Miller. She bought a lot of the equipment from Patch Studio, after the Randolph business closed. They photograph weddings together, combining Janet’s people skills with Jack’s technical acumen behind the lens.

“He’d run the camera and I’d run the show,” Miller said in a phone interview.

For 25 years, they took photographs of all the Little League ballplayers in Randolph. They were particularly active from 1990 through 2010.

“He has made a career out of being an independent photographer,” Tucker said.

While some of the images in the book come from Rowell’s commercial commitments, many are due to his own personal agenda. When he sees someone he wants to photograph, he asks them, and some subjects have sought him out. The people who stand in front of his lens all seem to share an energy.

“I think he is amazingly talented at capturing the human spirit,” Hudson said.

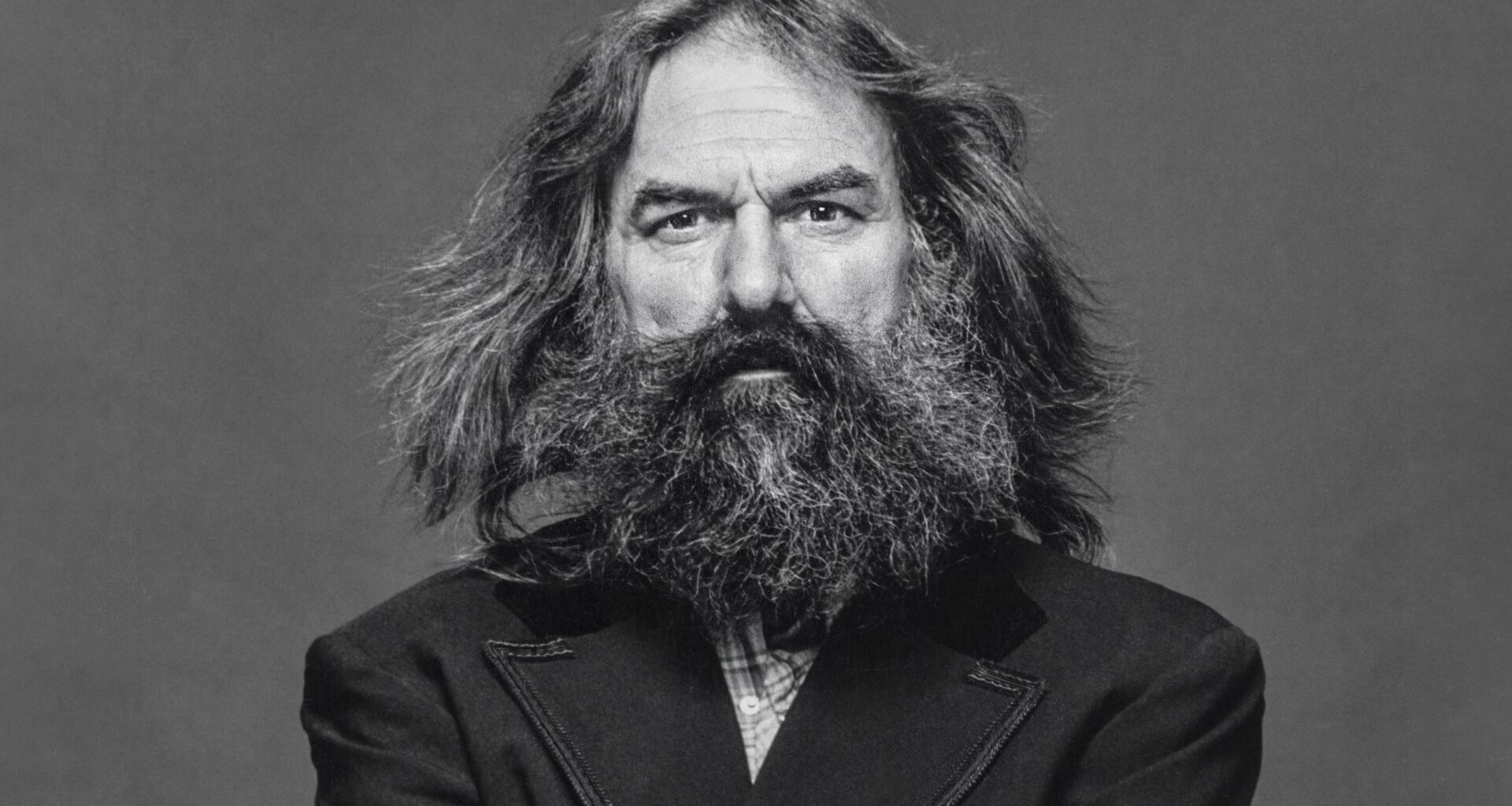

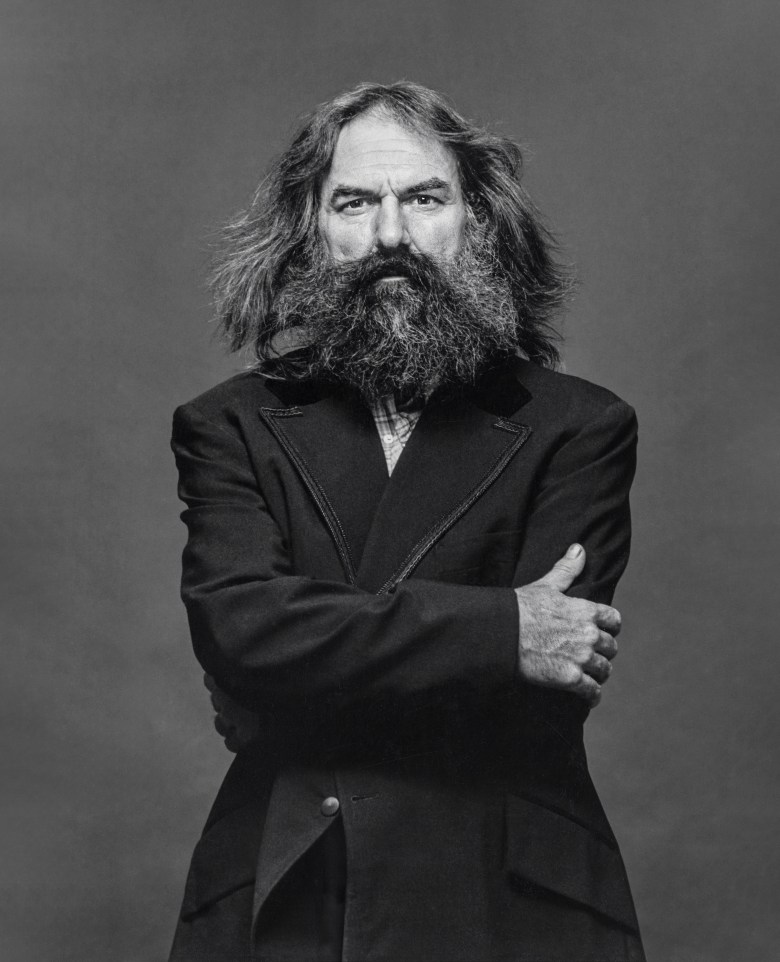

Another pair of photographs in the book illustrate Rowell’s chops, and the care he uses in making portraits. He twice photographed Bill Duval, a Randolph man with an unruly but majestic beard. (“Back in high school, he taught me how to roll a joint,” Rowell said.)

Bill Duval in a 1995 studio photograph, taken in Randolph, Vt. (Jack Rowell photograph)

Bill Duval in a 1995 studio photograph, taken in Randolph, Vt. (Jack Rowell photograph)

In the first image, taken on the street in 1993, Duval looks slightly vulnerable, turned to the side but with his face toward the camera. In the second photo, taken in 1995 in the studio, he stands square to the camera, wearing a black tuxedo jacket Rowell had handed him. He looks like a character in a 19th century Russian novel, capable of leading a proletarian movement or perpetrating great villainy. Duval died in 2008, at age 56.

“I think most of us take up photography to show how we see the world,” Jon Gilbert Fox, a longtime freelance photographer in the Upper Valley, said of Rowell. “I think in his case, it’s just another level that’s more intimate.”

What sets Rowell’s work apart is how deeply he’s rooted in his subject matter, Fox said: Vermont and its people. “He captures it so much better than everybody else, because he understands it.”

Everett Fleury with a large whitetail buck in East Roxbury, Vt., in 2007. (Jack Rowell photograph)

Everett Fleury with a large whitetail buck in East Roxbury, Vt., in 2007. (Jack Rowell photograph)

Tucker, who’s been an editor at Cosmopolitan and lived all over the world, now primarily in France, reconnected with Rowell when she asked if he’d photograph the participants of a memoir-writing workshop she was running at the Randolph Senior Center. Those portraits, which appeared in a book and a related exhibition at AVA Gallery and Art Center in Lebanon, made the project what it was, Tucker said.

That work led to a project at AVA photographing former employees at the H.W. Carter and Sons clothing factory, the building that now houses AVA.

“I think Jack connected with them in a really extraordinary way, because he’s so down to earth,” Bente Torjusen, AVA’s former longtime director, said. A photo of Torjusen’s grand-daughter, Vivienne, is in the book, as is a portrait of Thelma Follansbee, who worked at Carter for 36 years.

Tucker financed the making of the book from the sale of her mother’s Randolph house. Rowell’s is the first art book Korongo Press has put out. Her hope is that it will break even, so she can finance another book with the proceeds.

The book itself is unexpurgated, in that it contains portraits that likely haven’t seen as much daylight as some of Rowell’s magazine and commercial work. He’s always said his favorite subjects are “big fish and good looking women,” and the book includes some nude portraits, as well as a nod at one of Rowell’s most beloved subjects, Fred Tuttle.

Fred Tuttle, the star of John O’Brien’s “Man with a Plan,” in a 1994 portrait in Tunbridge, Vt. (Jack Rowell photograph)

Fred Tuttle, the star of John O’Brien’s “Man with a Plan,” in a 1994 portrait in Tunbridge, Vt. (Jack Rowell photograph)

Rowell helped shoot “A Man with a Plan,” the 1996 film that starred Tuttle more or less as himself, a Tunbridge dairy farmer who decides to run for Congress. Tuttle comes off as a cheerful everyman, but off camera he had a blue streak a mile wide. Rowell photographed Tuttle watching a porn flick in a New York City hotel room after Tuttle had appeared on a late night show. He looks like the same impish Vermont farmer.

Tuttle died in 2003, and his status in Vermont is beyond question. Rowell’s is similar. He’s had some health problems, which he asked a reporter not to mention, but which everyone else who knows him brought up. He had a triple bypass in 2004, then was nearly put on hospice care in 2019 and 2020 after a bout of pneumonia.

He’s spent the past few years immersed in his largely uncatalogued archive, putting together photographs for the book. There’s only one photograph in the entire volume that doesn’t have a person in it, which is an unusual view of Vermont, but a true one. Community is what the state has always been about.

Rowell doesn’t expect the book to change his modest life. “It’s kind of my legacy,” he said.

And it’s kind of Vermont’s legacy, too.

“Jack Rowell: Photographs” is slated for release at a party from 2 to 5 p.m. on Saturday, Nov. 22 at the White River Craft Center in Randolph. The Chandler Center for the Arts will hold a reception and author talk from 1 to 4 p.m. on Sunday, Nov. 23. For more information or to order the book, go to korongobooks.com.