The fossil hand of Paranthropus boisei and modern neuroscience challenge the old idea that labour created the human hand. The story now points to an older source: consciousness that shaped the coevolution of mind and hand.

Consider your hand. Rest it on a table and observe it. It is at once a biological machine of astonishing complexity and the most intimate part of you. It is an object in the world, a collection of 27 bones with muscles and nerves, and yet it is also the physical agent of your subjective will.

For the twentieth century philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, the hand presented a profound existential paradox: it was at once a detached instrument for acting upon the world and an intimate, inseparable extension of his very being.

This modern duality is resolved in an ancient Hindu prayer still recited by millions each dawn. In this tradition, the hands are consecrated not as mere tools but as the sacred dwelling of a divine trinity, the seat of Sarasvati, the Goddess of Knowledge, Lakshmi, the Goddess of Wealth, and Gauri, the embodiment of Strength. Thus, where one saw the duality of subject and object, the other perceived a sacred triune potential waiting to be awakened with the day.

Immanuel Kant saw it as “an extension of the human brain”, the physical link between the body and the soul. Through this remarkable organ, we act, we know and we speak, conveying feelings and emotions that lie beyond the reach of words.

This unique status presents one of the deepest questions in human evolution: what was the prime mover in the emergence of this astonishingly versatile and sensitive instrument?

Friedrich Engels Gives a Gospel Truth

For over a century, a powerful and elegant materialist account has held sway. It is a story of external necessity, a tale of “form follows function” written on a grand evolutionary scale. It is a materialist account most famously articulated by the nineteenth century philosopher Friedrich Engels in his influential essay, The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man (1876).

In this view, the external necessity of work, the chipping of stones, the butchering of carcasses and the endless struggle for subsistence, was the forge upon which the human hand was hammered into perfection. Labour, Engels argued, created man himself by first shaping the hand.

It is a compelling narrative of cause and effect, the demands of the world shaped the tool, and the tool in turn shaped its user. In a way one can even argue that this was quite an organic systemic conceptualisation given the age.

The powerful hypothesis of Engels became an unquestionable Party/State Doctrine.

But in the Soviet Union, Engels’s thesis was treated less as a testable hypothesis of science and more as an established truth of an infallible doctrine that explained humanity’s place in the material world.

When the inconvenient fact of chimpanzee tool making emerged, it presented a direct challenge not just to a scientific idea but to a political and ideological one. Instead of allowing the evidence to revise the theory, perhaps by concluding that the roots of labour are deeper and more common in nature than previously thought, the Soviet establishment did the reverse. They kept the theory intact and re-engineered the facts to fit it.

However the mystery of the evolution of the hand continued.

Tool usable hand adaptation outside the genus Homo?

For decades, the story of the human hand was told as a linear progression within our own genus Homo. It was a simple tale: as our direct ancestors like Homo habilis began to rely more on stone tools, natural selection favoured ever more dexterous hands, which in turn allowed for better tools, bigger brains and so on. The narrative was neat, progressive and self-contained.

Then, in the sun-scorched sediments of Koobi Fora, Kenya, palaeontologists unearthed a plot twist.

The Discovery

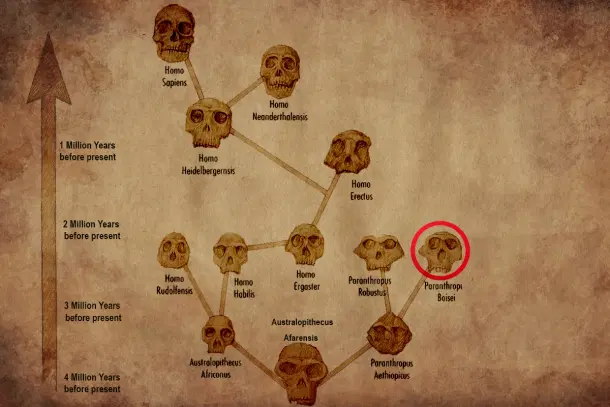

The discovery, published in Nature, was a 1.52 million year old partial skeleton catalogued as KNM ER 101000. It belonged not to a member of our genus but to our distant robust cousin Paranthropus boisei. Known for its massive jaws and enormous molars adapted for grinding tough fibrous plants, Paranthropus has often been cast as a specialised evolutionary side branch that ultimately went extinct. Apart from its skull, the rest of the body, particularly its hands, remained largely a lost mystery.

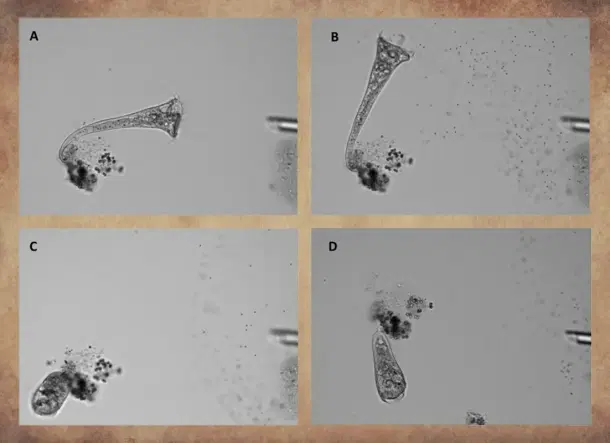

The KNM ER 101000 fossils changed that, presenting a hand that was both deeply familiar and utterly strange, a paradox that complicates the traditional story of human origins.

An Anatomical Puzzle

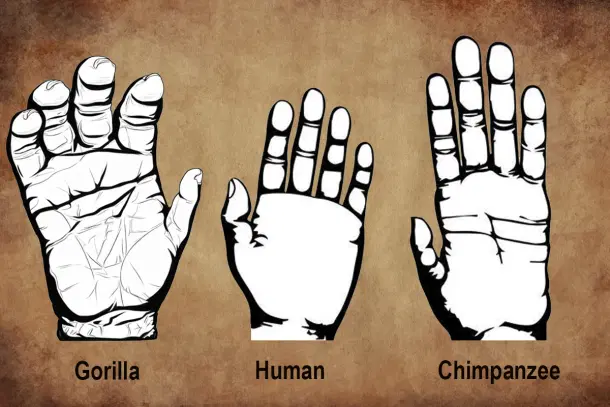

The hand of KNM ER 101000 is a mosaic of traits. On one hand, it possessed what the researchers describe as “essentially modern human like intrinsic hand proportions”. The thumb was long relative to the palm and fingers, an arrangement that would have enabled P. boisei to form “human like precision grips that require opposition of the distal pads of the fingers to that of the thumb”. The final bone at the tip of the thumb, called the distal phalanx, was broad and had a flattened wide end called an apical tuft. This is a feature associated with increased manual dexterity and forceful precision grips in later hominins, including Neanderthals and our own species. This is the anatomical hardware for sophisticated tool use.

![KNM-ER 101000: Paranthropus boisei palms fossil [from 'Nature'].](https://www.newsbeep.com/us/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/palmfossil.jpg)

KNM-ER 101000: Paranthropus boisei palms fossil [from ‘Nature’].

Yet, despite this potential, the overall architecture of the hand tells a different story.

The five long bones in the hand that connect the wrist bones (carpals) to the finger bones (phalanges) are called metacarpals. They form the structure of the palm. Here the first metacarpal, the bone at the base of the thumb, was exceptionally robust and strong. This suggests that Paranthropus had a powerful thumb capable of a strong grip, which would have been essential for manipulating objects, possibly for processing tough plant foods or even for rudimentary tool use.

Flexor muscles are the muscles in the forearm that pull on tendons connected to the fingers, causing them to bend or curl into a grip. In Paranthropus the finger bones show pronounced ridges and markings where these flexor muscles attached. Larger and more rugged attachment points indicate that these muscles were exceptionally powerful. This is strong evidence that Paranthropus had an incredibly strong grip, far more powerful than that of modern humans.

The fleshy muscular part of the palm located on the pinky finger side is called the hypothenar region. It is controlled by a group of three small muscles that help cup the palm and move the little finger. The fossil study of KNM ER 101000 shows that the hypothenar region was well developed in Paranthropus. It means the fossil hands show clear evidence of large and powerful hypothenar muscles. This contributed to their ability to form a forceful cupped grip.

In the last two aspects, the hand of P. boisei shows a striking convergence with the hands of modern gorillas.

This morphology is not primarily adapted for the delicate work of knapping flint but for “powerful grasping” and “intensive manual processing” of tough vegetation, a conclusion that aligns perfectly with dietary reconstructions for this species. Paranthropus appears to have used its powerful hands to grip, strip and process the abrasive grass-like plants that dominated its diet.

This evolutionary cousin lineage provides a perfect natural experiment. Because it is not on the direct line to modern humans, it allows us to test the Homo centred Labour First model. If Engels was right, the specialised tool ready hand should be unique to the Homo lineage, the one defined by labour.

KNM ER 101000 reveals the exact opposite.

The Principle of Evolved Potential

The significance of this find cannot be overstated.

It demonstrates that the key anatomical prerequisites for tool making dexterity evolved outside the Homo lineage and were not exclusively driven by the selective pressures of a stone tool culture. The discovery effectively decouples the evolution of a capable hand from the single deterministic force of labour as Engels conceived it.

Paranthropus had a tool ready hand but its daily life appears to have selected for that hand for an entirely different reason.

Discoverers of Exaptation: Elisabeth Vrba and Stephen Jay Gould.

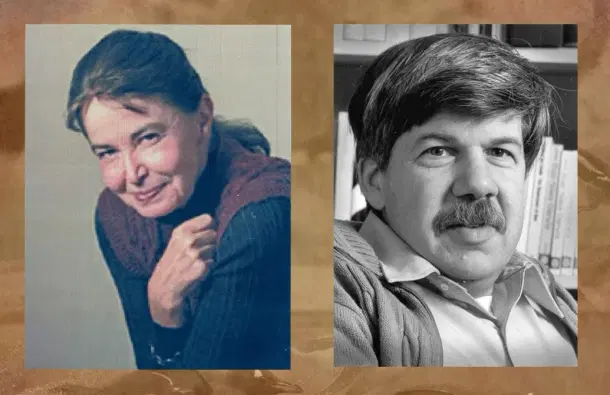

This reveals a deeper principle of evolution called exaptation, first delineated by palaeontologists Elisabeth Vrba (1942 to 2025) and Stephen Jay Gould (1941 to 2002, interestingly sympathetic to Marxism) in a famous 1982 paper. An exaptation is a feature that evolves for one purpose but is later co opted for another. The feathers of dinosaurs, likely evolved for insulation, were exapted for flight in their bird descendants.

The P. boisei hand is a stunning example of this principle in action.

The dexterity required to efficiently process tough plants incidentally created a hand that could be used for making tools, even if that was not its primary day to day function. This fundamentally weakens any deterministic theory that posits a single activity like labour as the sole architect of the hand.

Evolution is not a teleological march toward a predetermined outcome such as better tools. It is far more creative. It generates versatile structures that can be repurposed as the goals and behaviours of an organism change. The detailed study of KNM ER 101000, which is the fossil of P. boisei, shows that evolution produced a hand capable of many things. This immediately shifts the focus of the inquiry. If the anatomy itself does not mandate a single purpose, the crucial question becomes: what directs the use of that potential?

Answering this requires us to look away from the external activity and toward the internal agent, the conscious mind that chooses how to act.

Incidentally this was highlighted by none other than Engels’s own principal collaborator Karl Marx. Marx differentiated the simple production of a spider weaving its web from the work of a human architect by noting that the architect “raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality”.

This imagination, or let us say the intent or a mental template, is the non material precursor that defines human labour according to Karl Marx. The cognitive capacity for intentional goal directed action must exist before that action can be performed and must be consistent enough to become a significant selective pressure.

The Embodied Consciousness Evolving Forms and Functions?

While Marx, justifiably for the period, might have thought that this cognitive capacity could have evolved with complexity of the brain, empirical data from modern research suggests a profoundly different scenario.

The humble trumpet shaped single celled organism Stentor roeselii, when irritated by a pulse of particles, does not just react reflexively. It “cycles through a hierarchy of distinct responses”. First, it will try to bend away. If the irritation continues, it will reverse its cilia to push the particles away. If that fails, it will contract its entire body. Only as a last resort, if all else fails, will it detach and swim away.

Single-celled Stentor roeselii can choose from a variety of responses to a stimulus.

According to the researchers, this is a “rudimentary decision tree” executed by a single cell with no brain. This humbling observation suggests that “the capacity for choice, a form of consciousness… is a fundamental and ancient property of life itself, preceding the brain deep in evolutionary time”.

This suggests that consciousness in its most primal form precedes the brain in the realm of organic evolution on this planet. This primal consciousness must be defined in its proper evolutionary context.

It is not the complex self reflective narrative of modern humans. It is causal potency, the ability to voluntarily and consciously influence actions based on an internal model of the world and its goals.

For centuries, Western thought was dominated by a Cartesian model of the mind as a disembodied entity, a “ghost in the machine” that was fundamentally separate from the physical body. In this view, the brain thinks and the body merely executes its commands. Contemporary science has shown this model to be critically deficient.

Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson and Eleanor Rosch put forth the powerful concept of ‘Embodied Mind’.

In their foundational 1991 book The Embodied Mind, biologist Francisco Varela, philosopher Evan Thompson and psychologist Eleanor Rosch argued that cognition is not a set of representations about the world but emerges from the dynamic real time interaction between the brain, the body and the environment. Cognition depends upon the kinds of experience that come from having a body with various sensorimotor capacities.

This shifts the prime mover from the external environment (necessity) to the internal agent. This is the central insight of the enactive approach to cognition pioneered by the trio. In this view, cognition is not a passive mental calculation that happens before action. Instead, cognition is the embodied activity of an organism “bringing forth” a world of significance. The prime mover is the organism’s internal “will to interact”, its drive to make sense of its environment.

A 2025 study in Communications Biology offers compelling evidence for the co evolution of hands and brains. By analysing 95 living and fossil primate species with Bayesian phylogenetic methods, researchers confirmed the long held assumption that these two pivotal features evolved together.

The research demonstrates that the evolution of the dexterous human thumb did not occur in isolation but was part of a broader sustained coevolution with brain size, specifically the neocortex, across the entire primate order. Thus the critical link was not with the cerebellum, the brain’s processor for automated motor control. Instead, they found “a strong relationship with neocortex size”.

This is a crucial distinction. The evolution of the hand’s primary tool, the thumb, is not tied to the part of the brain that just moves it. It is tied to “the seat of higher cognition, sensorimotor skills and the parietal cortices”, the very hardware that allows an organism to enact a complex world.

More than two decades before these papers, in his 2002 book Hidden Connections, physicist turned author deep ecologist Fritjof Capra wrote the following in the context of language evolution in humans:

As the ability to control precise hand and tongue movements developed, language, reflective consciousness, and conceptual thought evolved in the early humans as parts of ever more complex processes of communication. All these are manifestations of the process of cognition, and at each new level they involve corresponding neural and bodily structures.p.65

One can say that the modern discoveries seem to validate Varela’s Santiago theory of consciousness and provide us with a radically different vibrant framework to study evolution.

From an Organ of Necessity to an Organ of Being

The story of our hands is not the simple utilitarian tale of tool making proposed by Engels. The fossilised hand of Paranthropus boisei provides the definitive empirical evidence to shatter that linear deterministic narrative. Neuroscience and evolutionary biology in turn reveal the hand and brain not as master and servant but as an inseparable symbiotic system providing the process for their co evolution.

The evidence now points to a revised causal chain. A fundamental involuted consciousness, the simple ancient will seen even in a single cell, provided the initial evolutionary spark. This internal drive selected for a more versatile dexterous hand, one that evolved its potential (exaptation) through mundane tasks like finding food, as seen in P. boisei.

This new physical capacity, a superior instrument for both action and perception, then fuelled the cognitive manual ratchet in the Homo lineage. This powerful cycle linking the hand’s hardware to the neocortex’s software accelerated the development of both our hands and our minds. Complex labour, art, language and technology were the magnificent results of this process, not its origin.

The hand is thus far more than an “organ of labour”. It is an organ of being. It is how we test the fabric of reality, communicate love, create music and build civilisations. It is the ultimate physical expression of the conscious self. In understanding the true origin of our hands, we move closer to understanding our true nature, a story driven not by the grim hand of necessity but by the boundless reach and emanations of consciousness.

And in this light, the ancient Hindu prayer to one’s own hands each dawn becomes tremendously significant.

Karagre Vasate Lakshmi, Kara-madhye Saraswati, Kara-moole Sthita Gauri, Prabhate Kara-darshanam

Journal References:

Mongle, C.S., Orr, C.M., Tocheri, M.W. et al. New fossils reveal the hand of Paranthropus boisei. Nature (2025). To download the paper click here.

Baker, J., Barton, R.A. & Venditti, C. Human dexterity and brains evolved hand in hand. Commun Biol 8, 1257 (2025). To download the paper click here.