A California dementia specialist has issued a stark warning that George Clooney‘s new film could romanticize assisted suicide and send a dangerous message to millions of vulnerable people living with Alzheimer’s.

Patty Mouton, a veteran gerontologist and palliative care expert from Orange County, told the Daily Mail that Clooney’s forthcoming movie In Love risks ‘glamorizing’ death and distorting the painful realities of illness, care, and family duty.

‘We have a very, very serious responsibility not to glamorize the notion of going out standing tall instead of on my knees,’ Mouton said. ‘That’s not life. Life is cyclic — it includes vulnerability. To avoid that is to limit our human experience.’

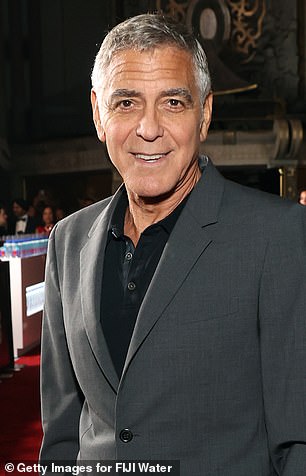

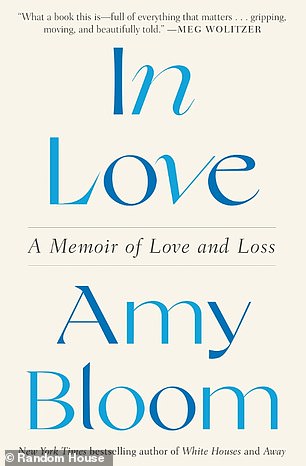

Clooney, 64, will star in In Love, based on Amy Bloom’s bestselling 2022 memoir In Love: A Memoir of Love and Loss.

The story follows Bloom and her husband, architect Brian Ameche, who was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s and chose to end his life at the Swiss assisted dying clinic Dignitas.

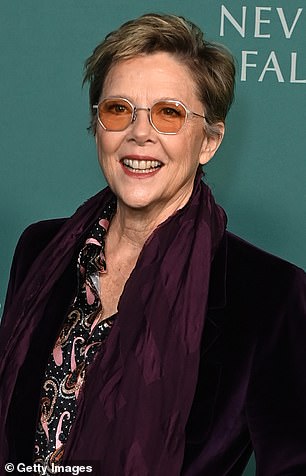

In the film, Clooney plays Ameche, with Annette Bening as Bloom. Filming begins in New England in November.

To many, it’s a tender love story about autonomy and dignity. Bloom herself called the memoir a reflection on ‘truth-telling and the right to face death without shame.’

Director Paul Weitz has called the story a ‘contemporary fable of love, wit, and existential stakes.’

Actors George Clooney and Annette Bening will star as the husband and wife couple grappling with an Alzheimer’s diagnose

California gerontologist Patty Mouton says Clooney’s forthcoming movie In Love risks ‘glamorizing’ death

But Mouton isn’t convinced. She fears the film’s Hollywood gloss and star power will mask the grim emotional and moral costs of assisted suicide — and make it seem like a graceful, noble exit rather than a desperate decision.

‘My hope is that the production team will be very, very careful not to emotionally incentivize people to think about assisted suicide in a more positive way,’ she said.

‘It’s not this convenient way to wrap up a life. It has far, far-reaching ramifications.’

The longtime dementia care specialist worries that Clooney’s portrayal could make those struggling with Alzheimer’s — and their exhausted loved ones — believe that choosing death is an act of courage or love.

‘What does it say about people who are not 100 percent strong — physically, emotionally, or cognitively?’ she asked.

‘Is it telling them that their lives are no longer worthwhile, and that it’s better to just end it before you become inconvenient or expensive?’

Drawing from decades at the bedsides of dying patients, Mouton said decisions like these are never made in isolation.

They’re shaped by fear, exhaustion, family tension, and medical bills that average around $70,000 per year for dementia sufferers, straining even premier health insurance plans.

‘I’ve had families say, ‘Can’t we end this sooner? It’s so expensive,” she revealed.

‘Sometimes the evidence suggests they don’t want their inheritance to be diminished by a long, drawn-out caregiving experience.’

She added that society must ‘reaffirm its duty’ to care for the sick with compassion, not convenience.

‘We have a duty to help people understand they’re going to be taken care of with love, respect, and dignity,’ she said.

‘We must disabuse people of the notion that the only way to live is with complete strength and cognitive ability.’

Clooney, pictured here with wife Amal, is one of Hollywood’s most recognizable stars

The movie depicts the real-life story of Amy Bloom and her husband Brian Ameche

They travelled to Switzerland’s notorious end of life clinic Dignitas, where Brian ended his life

Her comments come as Alzheimer’s cases rise across the US.

More than 7.2 million Americans currently live with the disease — a figure expected to double by 2050 as the baby boomer generation ages, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

The degenerative brain disorder robs people of memory, reasoning, and independence. It remains incurable.

And while 12 US states and Washington, DC allow physician-assisted dying, it is reserved for terminally ill, mentally competent adults expected to die within six months.

None permit it for dementia patients.

Connecticut — where Bloom and her husband lived — bans it altogether.

That’s why the couple traveled to Switzerland, where Dignitas offers assisted death to foreigners who are acting voluntarily and have decision-making capacity.

Dementia is problematic, as sufferers have to make end-of-life decisions before their capacity to consent to an assisted suicide is lost.

Mouton said the growing normalization of procedures, from Europe to Hollywood, risks warping the public’s moral compass.

‘If we are going to be a civilized society,’ she said, ‘aren’t we judged by the way we treat those who are most vulnerable?’

Mouton said she has never known anyone personally who went to Dignitas, but she has counseled countless families wracked with fear and guilt.

Many, she said, underestimate the emotional toll — or the potential for healing — in caring for loved ones through decline.

Celebrated American writer Amy Bloom co-wrote the screenplay for the upcoming movie

Her 2022 book describes how Brian, in his own words, wanted to die ‘standing tall, not on his knees’

She also warned that those who choose to die early may miss out on medical breakthroughs or moments of grace.

‘What if I’m the person who gets into a clinical trial and gets the magic bullet?’ she asked. ‘What if the next discovery comes six months later, and I’ve ended my life too soon?’

‘When somebody has a diagnosis like dementia, we might miss the opportunity to help the medical community learn more — or even get to a cure,’ she added.

For Mouton, end-of-life care isn’t just about dying — it’s about living meaningfully, right to the end.

‘I’ve seen siblings come together after not speaking for years,’ she said.

‘I’ve seen divorced couples reunite, so one can care for the other because it’s the right thing to do. These are extraordinary expressions of love and healing — and we miss them if we just end it.’

She’s witnessed patients who, even in their final days, still show small signs of wanting to live — accepting water, or a small bite of food.

‘Death is inconvenient,’ she said. ‘We have to accept that.’

Mouton doesn’t mince words about her opposition to assisted dying.

‘Suicide has detrimental effects on people,’ she said.

‘You can call it empowering, considerate, or intellectually superior. It’s still suicide — and it still has really strong, difficult, often negative impacts on the loved ones of the person who’s taken their life.’

She believes In Love — with its A-list cast and emotive storytelling — could unintentionally sell suicide as a moral act.

Mouton said she misses the days when films celebrated courage and endurance rather than convenience.

The nondescript room on the outskirts of Zurich, Switzerland, where Dignitas visitors end their lives

Doctor-assisted deaths are widely available in Canada, though heavily restricted in the US

‘I think it was better when we had more movies about courage — doing the right thing under terrible circumstances,’ she said.

‘There’s life after a diagnosis of dementia. Sometimes people live 12 or 15 years, and they’re not debilitated until the very end.’

‘The danger,’ she added, ‘is that people won’t understand that life isn’t over just because you have a serious diagnosis. There’s still love. There’s still learning. There’s still life.’

Her warnings echo those of disability rights advocates, who have also sounded alarms about Hollywood’s growing fascination with ‘beautiful’ deaths.

Ian McIntosh, executive director of the advocacy group Not Dead Yet, called In Love ‘a disability snuff film by any other name.’

‘Hollywood keeps depicting the everyday experiences of disabled people as a fate worse than death,’ he said.

‘Million Dollar Baby and Me Before You were panned for glorifying suicide as rational, even noble. In Love will be no different.’

Still, end-of-life choice advocates, such as Compassion & Choices, argue that controlled assisted dying offers autonomy and peace, not pressure, and that laws can include strict safeguards to prevent abuse.

Advocates say films like In Love help open long-overdue conversations about dignity, autonomy, and patient rights at the end of life.

In Love is being made by Smokehouse Pictures, the production company co-founded by longtime friends Grant Heslov (left) and George Clooney (right)

Whether to allow assisted dying stirs strong feelings, including in the UK (pictured), where a law change is being debated

Mouton said she doesn’t question Clooney’s intentions — only the potential consequences.

She hopes he and his team remember that behind every Alzheimer’s story is not just pain, but resilience.

‘It’s easy to make a movie about despair,’ she said. ‘It’s harder — and braver — to make one about endurance.’

‘My message to anyone with dementia is simple,’ she concluded. ‘You are not a burden. You are loved. You still matter.’