A new study has uncovered microscopic abnormalities in the blood of long COVID patients that may help explain the condition’s lingering symptoms. These hidden structures, discovered through advanced imaging techniques, show a significant departure from typical blood composition. The findings could reshape how we understand and diagnose long COVID. And if confirmed, they might finally provide a tangible target for future therapies.

Microclots And Immune Webs: Unseen Triggers Behind Lingering Illness

In the hunt for what fuels long COVID—a condition that continues to puzzle scientists years after the pandemic began—a team of international researchers has turned its attention to the blood. Their findings, published in the Journal of Medical Virology, reveal that people suffering from long COVID consistently show an unusually high presence of two little-known but potentially harmful agents: microclots and neutrophil extracellular traps, or NETs. These substances, although naturally occurring, appear to become harmful when they accumulate and interact in excessive or abnormal ways.

“These are not the types of blood clots you’d see in a stroke or pulmonary embolism,” explains Dr. Alain Thierry, lead author of the study and a geneticist at Montpellier University in France. Instead, they are much smaller—microscopic in fact—yet significant enough to disrupt blood flow in tiny vessels, particularly in areas like the brain, muscles, and lungs.

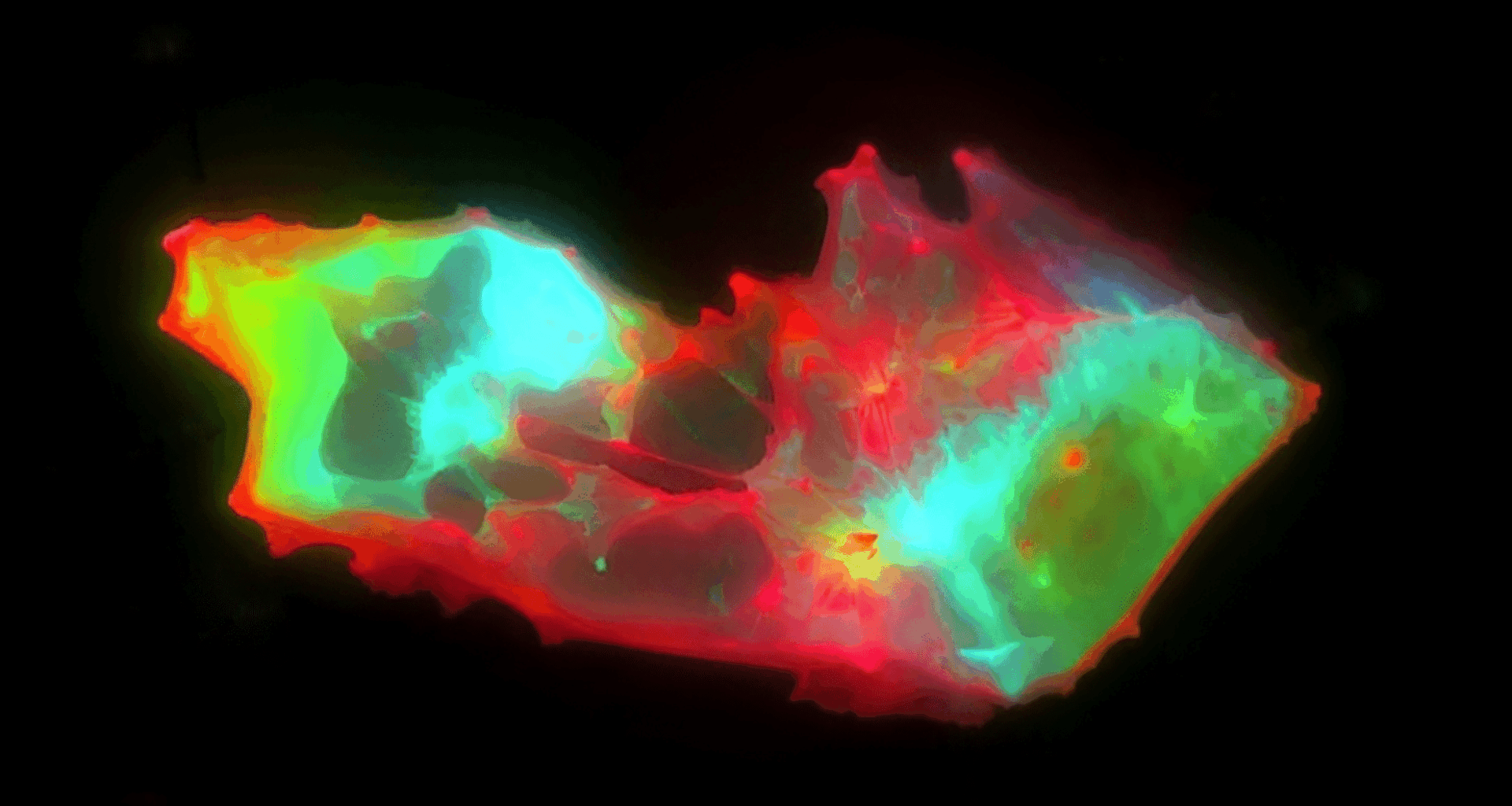

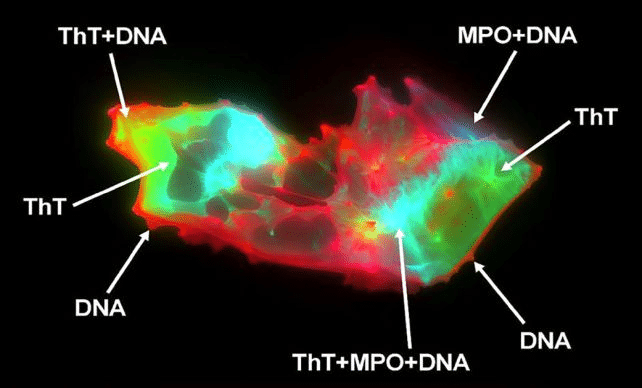

The team used imaging flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy on blood samples from 50 long COVID patients and 38 healthy individuals. They found that microclots were nearly 20 times more abundant in those with long COVID—and, more surprisingly, that NETs were not just floating freely, but were physically embedded within the microclots.

“This study shows a robust association between biomarkers indicative of thromboinflammatory activity and long COVID,” the team writes.

They propose that this entanglement of NETs and clots forms structures that are resistant to the body’s natural blood-clearing processes, a disruption that could directly explain symptoms such as brain fog, fatigue, and chronic pain.

When The Immune System Traps Itself: How The Body’s Defenses May Turn Against It

NETs are normally part of the immune system’s frontline defense. These sticky webs of DNA and enzymes, released by white blood cells, trap invading pathogens before they can spread. In typical cases, NETs are quickly dissolved after doing their job. But in long COVID patients, researchers found that NETs lingered in large quantities, intertwining with microclots and potentially amplifying the damage.

“The discovery of these biomarker linkages not only presents a possible novel diagnostic methodology,” the authors write, “but also novel therapeutic targets, offering prospects for future markedly improved clinical management.”

While both microclots and NETs had been previously observed separately in other diseases, their combined presence and physical interaction in long COVID patients marks a striking new insight. This synergy may explain why some people develop persistent symptoms long after the infection has cleared.

“This finding suggests the existence of underlying physiological interactions between microclots and NETs that, when dysregulated, may become pathogenic,” says Thierry.

In other words, the body’s own immune response may be creating self-sustaining, harmful blood structures that prolong illness.

This could also help explain why standard diagnostic tests often fail to detect long COVID—these interactions happen at a microscopic level and wouldn’t necessarily show up on conventional scans or blood work.

Toward A Blood-Based Test? AI Models See The Invisible

One of the more remarkable aspects of the study was the use of artificial intelligence to analyze anonymized blood samples. The AI was able to correctly identify long COVID patients with 91% accuracy based solely on the presence and patterns of microclots and NETs. This raises the possibility of developing a reliable diagnostic blood test for a condition that has, until now, largely been diagnosed based on patient-reported symptoms.

This could transform how doctors screen for and manage long COVID, and even open the door to personalized treatments aimed at breaking down these resistant structures in the blood. Clinical applications are still a long way off, but this research offers a promising roadmap.

While the authors caution that more research is needed to prove causation—not just correlation—the patterns they uncovered mark a significant leap forward. If confirmed by future studies, the blood of long COVID patients may hold the key not only to diagnosis but to treatment strategies that could finally bring relief to millions.