The latest ideas from President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans to reconfigure the Affordable Care Act face the same dilemma that every GOP alternative has confronted since Trump’s first term: The plan would impose its greatest costs on key groups within the Trump-era Republican electoral coalition.

With the approaching expiration of enhanced subsidies that help Americans buy insurance through the ACA, Republicans are staring down the political threat of large premium hikes for up to 20 million people and the loss of coverage for millions more. In response, Trump and key congressional Republicans have proposed to convert all or part of the ACA subsidies into direct payments to individuals to pay for health care.

That approach could initially benefit younger and healthier consumers. But most experts agree it would increase costs and diminish access for older, lower-income and non-college-educated people with greater health needs. And those older, working-class families are now more essential to the Republican than Democratic electoral coalition.

So while the policy mechanisms are different than what Republicans employed when they sought to “repeal and replace” the ACA during Trump’s first term, the new ideas touted by the president and allies such as Republican Sens. Rick Scott of Florida and Bill Cassidy of Louisiana present the GOP with the same political and policy problem: a collision between their ideological preferences and the material interests of their own voters.

The new proposals are “a variation on the same theme,” as the Republican alternatives to the ACA in 2017, said Sabrina Corlette, research professor at Georgetown University’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms. “There are multiple different ideas swirling around. But I have not heard any idea from (Republicans) that would not result in higher premiums for people under the Affordable Care Act and less protections for people with preexisting conditions.”

This latest flurry of proposals from Trump and other GOP leaders marks a stunning, if perhaps not entirely planned, change of direction. During the campaign, Trump downplayed discussion of the ACA, and congressional Republicans this year conspicuously avoided the kind of head-on repeal effort they launched in 2017.

But now they are on course to threaten the twin pillars of the ACA that have reduced the number of Americans without health insurance to only 8% as of 2023, the lowest level the Census Bureau has ever recorded.

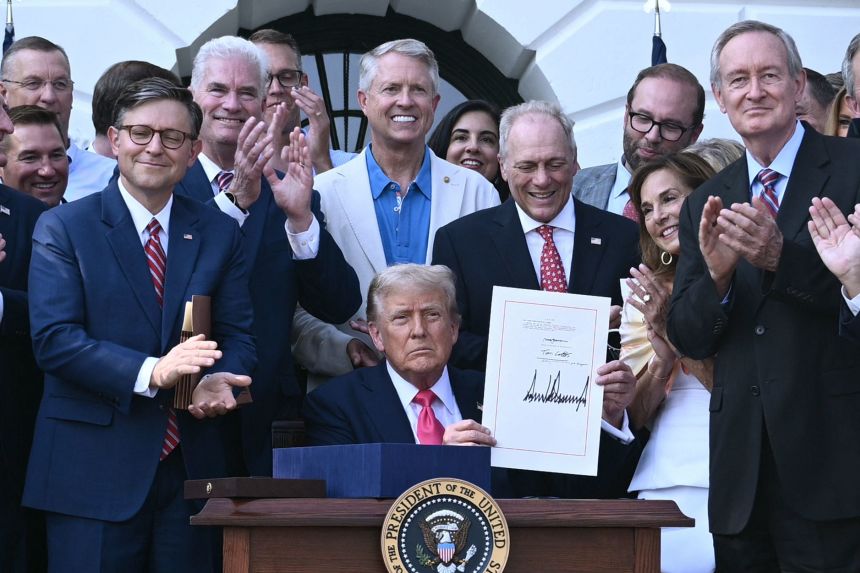

In the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” last summer, Republicans imposed big cuts targeted primarily at the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid eligibility to more working-poor adults. About 20 million people have obtained Medicaid coverage through that expansion, but the GOP bill, over the next decade, would rescind coverage for about 10 million people and cut funding for the program by more than $900 billion, according to projections from the Congressional Budget Office.

Now — either by allowing the enhanced subsidies approved under President Joe Biden to expire or by potentially replacing them with a new system of direct payments — Republicans appear poised to remake the ACA exchanges that more than 24 million people use to purchase private insurance.

Taken together, this two-front pincer move against the ACA has catapulted Republicans back into precisely the sort of fundamental health care debate they appeared determined to avoid when Trump took office in January.

“Coming into this year, it did not seem like Republicans wanted another fight over health care and the Affordable Care Act, but they seem to be inviting that fight,” said Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at KFF, a nonpartisan health care think tank. Between the cuts in Medicaid and proposals to transform the insurance subsidies, Levitt said, “it all adds up to whole another ‘repeal and replace’ debate.”

Trump and other Republicans have introduced a new twist into the ACA debate with their calls for redirecting the money the federal government currently spends on tax credits to help people buy insurance on the exchanges.

In a social media post earlier this month, Trump seemed to endorse entirely converting those credits into direct payments that the federal government would deposit into tax-favored accounts individuals could spend on health care expenses.

Sen. Scott on Thursday released a proposal to convert the entire ACA tax credit into payments into “Trump Health Freedom Accounts” in states that agree to participate. Sen. Cassidy has said he’s formulating a somewhat more limited proposal that would leave in place the original tax credits provided under the ACA, but transform the enhanced subsidies approved under Biden into direct payments. The Paragon Institute, a health care think tank close to the administration, has similarly proposed to fund payments to individuals from the ACA spending that helps low-income families meet their cost-sharing obligations under the law.

These ideas raise many of the same issues as the GOP effort to “repeal and replace” the ACA during Trump’s first term.

Before the ACA, people with preexisting health conditions had found coverage in the individual insurance market extremely difficult to obtain because insurers could either charge them prohibitive rates or refuse to write them policies at all.

The ACA barred those practices through an interlocked suite of changes. The law required insurers to sell plans to all consumers at comparable prices, regardless of their health status. (The only factors insurers could use to differentiate premiums were age and tobacco use.) It limited how much more insurers could charge older than younger consumers. The law also required insurers to provide a robust baseline of “essential health benefits” in all policies with the goal of preventing companies from luring healthy Americans into skimpier and less expensive plans.

As I wrote in 2017, in all these ways and more, the ACA approach “prizes solidarity.” It required healthy people to buy more comprehensive plans than they might prefer in order to help coverage remain affordable and available for older people with greater health needs. It also amounted to younger people spreading risk across their own lifetimes by paying more when they are young so that coverage will be available when they are old and will likely have greater health needs. As Corlette told me in 2017, “In many ways under the law the young and healthy are subsidizing the older and sicker on the theory that eventually all of us get older and sicker.”

The most glaring political vulnerability of this approach was that it required younger and healthier people to help fund the coverage for those with greater health needs. Conservatives complained that the ACA’s risk-sharing functioned as a kind of stealth tax.

The repeal bill that House Republicans passed in 2017 — and the major Senate proposal that year from Cassidy and Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina — both aggressively moved to unravel the ACA’s risk-sharing in a variety of ways.

Republicans touted these changes as providing people more freedom to pick the health insurance they need and argued — justifiably, many experts believed — that loosening the ACA’s risk sharing would lower premium costs for healthier people. (Even if it left them with more financial exposure should they face a major health problem.)

But Democrats successfully focused public attention on the other half of the equation: the danger that the Republican changes (like letting states waive most of the ACA regulations) would raise costs and diminish access for people with preexisting conditions.

In hindsight, that shift was the hinge point in the long partisan struggle over the law. When former President Barack Obama and congressional Democrats initially passed the ACA, it was largely discussed as a program for the uninsured; during the repeal debate, its image changed to a program protecting the larger universe of people with preexisting conditions. That lifted public support for the ACA to previously unmatched heights and made the attempt to rescind the law a major vulnerability for the GOP in the 2018 election, even after defections from three Senate Republicans doomed the repeal effort.

In the 2018 election, 57% of voters said they trusted Democrats more than Republicans to protect people with preexisting conditions, and almost 90% of them voted for Democratic House candidates, according to the exit polls conducted for a consortium of media organizations including CNN. The ACA has remained overwhelmingly popular since: in the latest KFF tracking poll nearly two-thirds of adults expressed a favorable view of it.

Echoes of ‘repeal and replace’

The new GOP proposals to transform the ACA subsidies into direct payments to individuals array the parties in much the same formation as the 2017 debate. Now, as then, Republicans frame their plans as a way to provide more choice to consumers and to promote greater competition in health services that will constrain costs.

“We empower patients to shop to find the best deal for their dollar that drives competition and that lowers cost,” Cassidy said in a Senate floor speech this month. He often notes that transforming the enhanced subsidies into direct payments would channel all the money toward consumers, while the existing structure allows insurers to pocket 20% in overhead and profit.

As in 2017, Democrats and many independent analysts are warning that the GOP proposals will separate the healthy from the sick and leave the latter facing much higher costs and diminished access. Converting the ACA tax credits into direct payments could prove attractive to healthier people, many experts say, since they could purchase high-deductible plans with lower premiums and use the new accounts to cover their out-of-pocket costs; they might also be allowed to use the money for expenses more tangentially related to health, like gym memberships or prescription sunglasses.

But if those healthier consumers abandon the comprehensive plans, sicker people who need that heftier coverage would face higher premiums — which would prompt even more healthy people to flee. (In insurance marketplaces that’s called a “death spiral.”)

Consumers with the greatest health needs are “the people who are going to be really harmed by this,” said Sherry Glied, a professor at New York University’s Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, who has extensively studied health savings accounts.

Cassidy’s developing plan, for instance, would both push and pull people toward less comprehensive coverage. From one direction, it would eliminate the enhanced subsidies, which would make it more difficult to afford the more robust ACA “gold” or “silver” plans. From the other direction, it would only convert those subsidies into direct payments if individuals chose a less comprehensive “bronze” plan that requires high deductibles and larger total out-of-pocket spending. Those plans, which now account for about 30% of those sold on the ACA marketplaces, appeal more to people with fewer health needs than those facing chronic problems. (Scott’s plan would push people even harder toward less comprehensive plans by allowing the enhanced subsidies to expire completely.)

The complication for Republicans is that their Trump-era electoral coalition now includes millions of working-class voters — many of them older, with modest incomes and without four-year college degrees — who are on the wrong side of these trade-offs.

Far more House Republicans than Democrats represent districts where the share of residents facing serious health problems — including diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, breast cancer deaths, cardiovascular problems and a lack of health insurance of any kind — exceeds the national average, according to an analysis I conducted earlier this year with the New York University Grossman School of Medicine.

Data from KFF about the distribution of preexisting health problems reinforces that picture. Analyzing federal data, KFF has previously reported that the estimated 54 million working-age adult Americans with preexisting conditions tilts toward people over 45. In a new analysis conducted for CNN, KFF found that people without a college degree are more likely than those with advanced education to suffer from a preexisting condition. People with less income, likewise, are more likely to face preexisting conditions than the more affluent.

Leslie Dach, chair of the liberal advocacy group Protect Our Care, predicted all the Republican moves this year against the ACA will affect next year’s midterm election even more than the repeal drive shaped 2018. Compared with that time, he said, “The law is more popular; it’s more baked in. They are doing this for no reason and people will know that.” With his call for converting the tax credits into direct payments, Dach said, Trump is “pushing a suicide pill” on congressional Republicans.

Michael Cannon, director of health policy studies at the libertarian Cato Institute, said Republicans have left themselves in a difficult position. Extending the enhanced subsidies would amount to “an expansion of Obamacare that is likely to depress Republican turnout in the midterms,” he predicted. At the same time, he said, while “there is merit” to the idea, he considers it unrealistic that the party can build consensus about designing individual payments to replace the subsidies in the few weeks before they expire at year’s end.

The Republicans’ best option, Cannon argues, is to pass legislation codifying the regulatory changes during Trump’s first term (and later repealed by Biden) to expand access to lower-cost short-term insurance plans exempt from many ACA mandates. But Democrats and other defenders of the ACA consider those plans “junk insurance” that would have the same effect as the other GOP proposals of luring healthy consumers, unraveling the risk pool, and ultimately endangering people with chronic health problems.

In the prolonged struggle between the parties over health care all roads seem to lead back to that same place. Whether in 2017 or today, across all the Republican alternatives to the ACA, “the consistent theme is segregating sick people from healthy people,” as Levitt put it, in the name of promoting autonomy, choice and competition. For Democrats, the top priority is sharing risk through collective action — whether by requiring the healthy in the individual insurance market to subsidize the sick, or by requiring taxpayers to fund coverage for the uninsured through the ACA, Medicare and Medicaid.

The details of federal health care policy may be eye-glazing, but more than almost any other major issue, they map the space between the parties’ contrasting visions of what we should expect not only from the federal government, but from each other.