In a time when health providers, initiatives and programs are facing funding uncertainty, the future of a therapeutic court housed in Whatcom County’s health department is, according to its supervisor, secure.

Unlike many court-based therapeutic courts, which intervene to support the mental health of people who’ve entered the justice system, Whatcom County’s Mental Health Court is a health department program. Funded by taxpayers and hosted in Whatcom County District Court and Bellingham Municipal Court, the program served 155 individuals in its first decade.

While connecting participants to mental health services, the nearly two-year-long program has helped nearly 90 graduates have their charges dismissed in the last decade. Since the program is based in the health department, a public health approach to the justice system is a core principle, not just a feature.

“The justice system has difficulty resolving cases with individuals that have serious mental illness,” District Court Judge Angela Anderson said. “Any time we have people in and out of the justice system repeatedly, that’s a health crisis.”

During participants’ required weekly or bi-weekly check-ins with Anderson, compliments for pro-social activities are aplenty, as is clapping. Reassurances are preferred over punitive and authoritative measures. At a recent October session inside Anderson’s courtroom, a participant who relapsed was given a writing assignment, rather than community service.

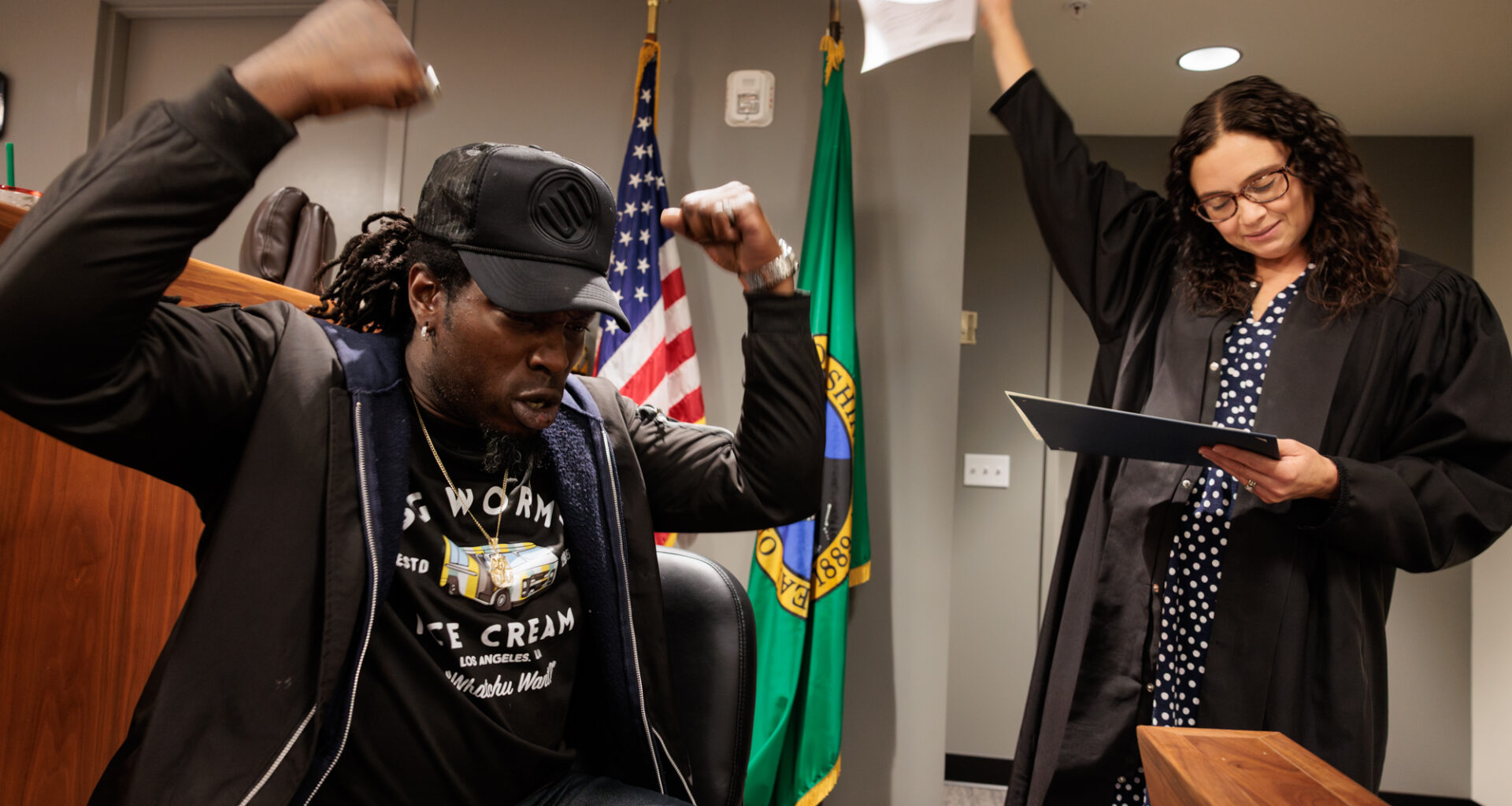

Although the courtroom is small and intimate, blink for too long, and you may miss one participant’s long-awaited moment: the motion to dismiss a case. The subsequent roar from inside couldn’t have been mistaken for anything other than graduation.

More than two years ago, when Atiba Fleming, 47, first heard of mental health court, he said two thoughts occurred: I need that, and two years sounds incomprehensibly distant.

When Fleming’s dog, Bug, was stolen from him, efforts to retrieve the 7-year-old led him to jail, where, eventually, he was relieved to qualify for the program that required weekly check-ins with Anderson.

“I thought I wasn’t going to make it,” Fleming said. “I thought it was going to be a hot mess, but it wasn’t. I didn’t know it was going to be this short and cool.”

From left, Judge Angela Anderson, Atiba Fleming and Jerome Edge have a conversation after mental health court ends. Fleming’s dog, Bug, waits to leave the courtroom. (Santiago Ochoa/Cascadia Daily News)

From left, Judge Angela Anderson, Atiba Fleming and Jerome Edge have a conversation after mental health court ends. Fleming’s dog, Bug, waits to leave the courtroom. (Santiago Ochoa/Cascadia Daily News)

A decade of partnerships

The program, which blends intensive case management with judicial oversight, has capacity for up to 50 people at a time. However, it’s currently serving 28 participants, with seven in the municipal program and 21 in district court.

“The limiting factor for our district court, it’s all docket space. There isn’t enough time with a judge and time in a courtroom, to accommodate more,” said Robin Willins, the program’s supervisor. “We’re doing a lot of extra things that we won’t be able to do when we’re full.”

Anderson says she spends half a day a week doing mental health court work. The four hours a day equates to the time it would take her to oversee 15 small claims or four protection orders or 60 criminal statuses, Anderson said.

If Anderson were to jam participants through her courtroom and into the program just to be at capacity, she says it’d lower effectiveness and in doing so deteriorate government officials and the public’s trust in the program.

“We’re really at capacity with our three judicial officers,” Anderson said. “I’m never going to turn away a participant but I want to focus on the individual, quality over quantity.”

In 2024, the program received $474,488 from the county’s Behavioral Health Fund, and is on track to receive $491,026 in 2025 and $505,332 in 2026, according to the county. The 2026 funds from the behavioral health sales taxes comprise the entirety of the program’s adopted expense budget.

“Without the behavioral health tax, mental health court wouldn’t exist,” Willins said.

Of the 2024 funds, $78,000 were spent on contracts with community partners, including Catholic Community Services, Compass Health, Lake Whatcom Treatment Center, Lifeline Connections and Unity Care NW. The behavioral health tax funds the program’s three staffers, all of whom are employees of the county’s health department. (The program has an unpaid intern, too.)

“There’s probably people in our community who feel like, ‘Wow, this is a lot of money and resources in court time poured into individuals,’” Anderson said. “These are high utilizers of the system, they’re going to cost this community a lot of money one way or the other. We’re going to spend it locking them up in jail or we can put it towards mental health court and raise these people out of this cycle.”

County employees who work with the mental health court set up decorations inside a courtroom in celebration of Atiba Fleming’s graduation. (Santiago Ochoa/Cascadia Daily News)

County employees who work with the mental health court set up decorations inside a courtroom in celebration of Atiba Fleming’s graduation. (Santiago Ochoa/Cascadia Daily News)

Participants’ mental health treatment is covered by their insurance, which for most in the program is Medicaid, or Apple Health, in Washington. Looming changes to Medicaid following President Donald Trump’s tax and spending law could cause the program to initiate some changes, Willins said.

“If Medicaid eligibility gets drawn back, unless people are eligible for Medicaid or that reimbursement gets cut back, our program structure relies on the services being provided through their mental health provider,” Willins said.

The program is supported by the behavioral health fund, a vast resource that has helped thousands while needing triage to avoid going into the negative. Despite the program’s reliance on tax revenue, which is down, Willins says they’re in good shape, adding that at the decade mark, there isn’t anything they can foresee that’d jeopardize the program.

“Mental health court, we are in a pretty good place, we’re fortunate,” Willins said. “In a perfect world, mental health court shouldn’t exist, somebody struggling with their mental health needs shouldn’t end up in the criminal legal system.”

The next decade

In the next decade, Anderson hopes to see participants enter the program quicker as well as more partnerships. More court time, space and resources would be nice, too, she said.

“I feel we’re very likely to be sustained,” Anderson said.

“I want more individuals that are really struggling, let us work with them while they’re struggling versus them having to spend a year or two on their own trying to figure it out,” Anderson said. “We have the resources, come to me.”

Some legal professionals warn that mental health court programs can distract policymakers from other solutions, such as community mental health care. This skepticism is warranted and carries weight, Anderson said, explaining that the program shouldn’t be the only solution.

“If it is, we’re not addressing mental health until someone commits a crime. As a community, we need to make sure we’re addressing mental illness before someone commits a crime,” Anderson said.

Outside a Whatcom County Courtroom, a red velvet cake with the word “Freedom” written in icing awaits Atiba Fleming, the most recent graduate of the county’s mental health court program. (Santiago Ochoa/Cascadia Daily News)

Outside a Whatcom County Courtroom, a red velvet cake with the word “Freedom” written in icing awaits Atiba Fleming, the most recent graduate of the county’s mental health court program. (Santiago Ochoa/Cascadia Daily News)

If the county’s forthcoming justice center includes a robust diversion operation that helps people get care rather than jail time, then those people wouldn’t be charged with anything and thus wouldn’t need mental health court. The impact, if any, that the new justice center will have on the mental health court program remains unknown. It could be another entry point for the program.

The program, Fleming said, was one of the first times he initiated recovery measures on his own.

“It felt good knowing that I put in the work, and right now, I’m still sober,” Fleming said, adding that without the program, “that’s not something I’d like to think about. I’d probably be dead.”

“Atiba, you’ve worked so hard to get here, the sky is the limit,” one participant said to Fleming on his graduation day. “You can do anything you put your mind to, and you’ve accomplished a big task right now.”

Owen Racer is a Report for America corps member who covers health care and public health in Whatcom and Skagit counties. Reach him at owenracer@cascadiadaily.com; 360-922-3090 ext. 101. Learn more and donate at cascadiadaily.com/rfa.