For years, federal policymakers have tweaked lung cancer screening guidelines as if the barrier to saving lives is a math problem. Add a few years to the eligibility age. Drop a few pack-years — a measure combining how much and how long someone has smoked. Remove a quit-time rule. Repeat.

But it was never really a math problem. A new study in JAMA Network Open makes clear what many of us in cancer prevention and control have been warning for over a decade: No amount of technical adjusting will fix a system built on stigma.

I see the effects of this every day. As a behavioral scientist and nurse practitioner, I’ve sat with hundreds of patients confronting the potential of a lung cancer diagnosis. I’ve watched people brace themselves before they say the words “I used to smoke,” even when they quit decades ago. I have watched people who have never smoked rush to explain why they got lung cancer at all.

These reactions aren’t personal quirks. They are predictable responses to a system that has taught people to expect judgment.

That system is failing on its own terms. The new study examined nearly 1,000 people diagnosed with lung cancer at a major academic medical center and found that 65% would not have qualified for screening under today’s U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) criteria.

Why so few get screened for lung cancer, the deadliest cancer in the U.S.

Let that sink in: Two-thirds of people who develop the deadliest cancer in the country would never have been offered the one test proven to save their lives.

And it gets worse. Even if policymakers expanded the criteria — lowering the pack-year threshold, removing the quit-time requirement, widening the age range — almost 40% of cancers would still be missed.

The population ineligible for screening is not random. It is disproportionately women, Asian Americans, and people who have never smoked. These are groups the current framework structurally misclassifies as “lower risk,” despite real-world evidence to the contrary.

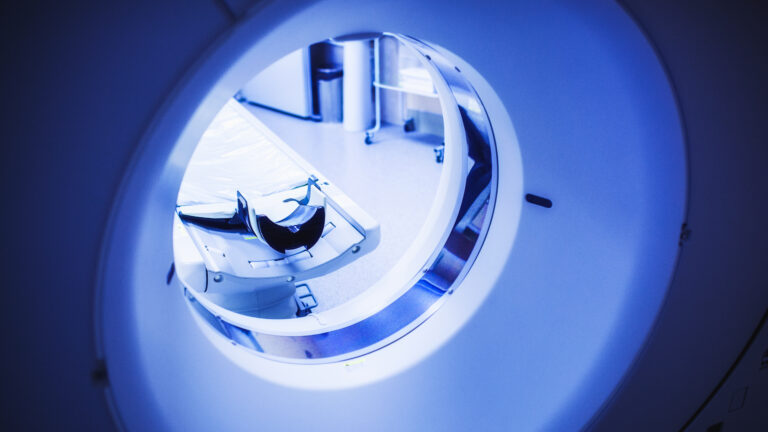

Only one approach captures nearly all of them: age-based screening. The test itself is straightforward: a low-dose CT scan that takes about 10 minutes and exposes patients to minimal radiation. Screen everyone ages 40 to 85, regardless of smoking history, and you detect 94% of cancers and prevent more than 26,000 deaths every year. The cost is lower than what we routinely pay for breast or colorectal cancer screening. The number needed to screen to prevent one lung cancer death is 320. For comparison, mammography requires screening about 1,339 women to prevent one breast cancer death, and colonoscopy requires screening about 455 people to prevent one colorectal cancer death. Yes, broader screening means more false positives and follow-up imaging, but these trade-offs are manageable — and far less burdensome than the status quo, which misses two-thirds of cases entirely.

You would think this evidence would be enough to prompt immediate policy change. But there’s a deeper problem that policymakers fail to acknowledge.

Age-based screening would eliminate smoking history as an eligibility requirement. But even that fix will fail if clinicians continue to interrogate patients about tobacco use during the encounter, or if public messaging keeps framing lung cancer as a “smoker’s disease.” The stigma is baked into the culture of lung cancer care, not just the eligibility criteria.

Today, lung cancer is the only major cancer that requires patients to recount their past behavior to determine whether they deserve early detection. No other screening program requires a behavioral confession. No other cancer demands a precise accounting of past conduct as a gateway to lifesaving care.

This is not a risk assessment. It is a judgment system designed as one. And it is a policy choice that suppresses exactly the participation we need.

In my research studies on lung cancer stigma, participants have shared stories that still stay with me. One man in his early 60s, a former construction worker who had quit smoking more than a decade earlier, told me he postponed his screening appointments repeatedly because he felt embarrassed to talk about his past tobacco use. Even after years of being smoke-free, he worried preventive care would turn into a judgment of the years when cigarettes were a coping mechanism for demanding work and family strain.

Another participant, a woman in her 50s who met the eligibility criteria, explained that she avoided screening because she believed she had “brought this on herself” by smoking in her teens and 20s. She told me she did not feel entitled to use health care resources for something she associated with personal failure.

‘But I never smoked’: A growing share of lung cancer cases is turning up in an unexpected population

Their experiences reflect patterns I see across my research: self-blame, anticipated judgment, and internalized stigma routinely suppress participation in lung cancer screening. Their stories are not just anecdotes; they are data points that reveal how stigma shapes real-world behavior long before a person arrives at a clinic.

Fewer than 1 in 5 eligible Americans undergoes lung cancer screening — the lowest uptake of any major cancer screening in the country. Breast and colorectal screening rates are more than triple that number. Stigma is not a secondary factor here. It is the central explanation.

Decades of behavioral science show that stigma reduces disclosure, undermines trust, and discourages engagement with health systems. These are not abstract effects. They shape whether someone shows up for screening at all.

Yet the USPSTF continues to treat smoking history as a kind of eligibility exam, ignoring radon exposure (the second leading cause of lung cancer), air pollution, occupational hazards, and genetic predisposition.

Meanwhile, clinicians must rely on pack-year calculations that studies show are missing or inaccurate in over 80% of medical records — errors that disproportionately harm women and Black Americans, who develop lung cancer at lower pack-year exposures than the guidelines assume.

The new study reveals something else policymakers should take seriously. Patients who were ineligible for screening had better survival than those who met the criteria: a median of 9.5 versus 4.4 years. The authors attribute part of this to tumor biology. But there is another possibility worth considering: These patients’ cancers were caught incidentally, during imaging for unrelated issues. They bypassed the stigma-laden screening pathway altogether.

When the system meant to save people is one they avoid, something is broken — not at the individual level, but at the policy level.

This demands a different kind of response.

The USPSTF should move toward age-based screening criteria, or at least a hybrid model, that no longer hinges on a detailed smoking history. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services should stop tying reimbursement to burdensome pack-year documentation that blocks access. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health should fund stigma-reduction interventions with the same vigor they apply to “awareness” — because awareness cannot overcome shame.

Health systems have their own work to do. Clinicians need stigma-informed communication training. Electronic medical records need prompts that do not require perfect recall from patients. And public messaging must reflect the complex etiology of lung cancer rather than reducing it to tobacco use alone.

Age-based screening is good science. But science alone is not enough. If stigma continues to shape how we design, communicate, and deliver lung cancer screening, participation will remain low, disparities will deepen, and thousands of preventable deaths will continue every year.

The deadliest cancer in America does not need more incrementalism. It needs policymakers willing to confront the barrier they built into the system from the beginning.

Lisa Carter-Bawa, Ph.D., M.P.H., N.P., is a behavioral scientist and director of the Cancer Prevention Precision Control Institute at the Hackensack Meridian Center for Discovery & Innovation.