Most Americans would consider losing hard-earned assets—their homes, savings, or family heirlooms—an intolerable outrage. Imagine, then, the government quietly brokering backroom deals to dispose of our collective inheritance: historic buildings, public art, and national landmarks. These are the worries of preservationists concerned about the new “accelerated disposals” process, which mandates the rapid sale of our public assets without much public awareness and clarity about how the prospective sales will impact historic resources, such as important buildings and art. In this climate, America’s historic architecture, public lands, and priceless artworks now seem at greater risk of being sold off for little public benefit.

The Wilbur J. Cohen Building in Washington, D.C.—previously the Social Security Building, later renamed in honor of a key figure in the development of Social Security policy—is managed like most federal office buildings by the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA), the agency overseeing the government’s new “accelerated disposals” process. The building is architecturally important and notably includes some of the most important New Deal–era murals.

Architecturally, the Cohen building stands apart in Washington, D.C. It was designed by early 20th-century architect Charles Z. Klauder. (Carol M. Highsmith/ Library of Congress)

Architecturally, the Cohen building stands apart in Washington, D.C. It was designed by early 20th-century architect Charles Z. Klauder. (Carol M. Highsmith/ Library of Congress)

Architectural Legacy

Architecturally, the Cohen building stands apart in Washington, D.C. Designed by early 20th-century architect Charles Z. Klauder. Visually the building’s commanding limestone facade combines prewar art moderne and stripped classicism with a subtle Egyptian flair. Details like Prairie Brown granite panels, cavetto cornices, and windows framed by slightly slanted pilasters, echoing the pylons of Luxor or Edfu, demonstrate Klauder’s ability to merge traditions and develop something clever, unique, and refreshing. The result is a building that fits comfortably among the Greco-Roman iconography more commonly found across the capital.

A series of central yellow-bronze Westinghouse escalators aid in functional vertical transportation. (Carol M. Highsmith/ Library of Congress)

A series of central yellow-bronze Westinghouse escalators aid in functional vertical transportation. (Carol M. Highsmith/ Library of Congress)

Inside, the materials and craftsmanship are quintessential art deco: bronze doors, Vermont verde marble paneling, green-gray terrazzo flooring, and Granox marble. Thin bronze crown moldings and lamps enhance that ambiance. A series of central yellow-bronze Westinghouse escalators aid in functional vertical transportation and speak to Klauder’s adeptness in transitional-period design.

The “Sistine Chapel of the New Deal”

The building’s murals arose from the New Deal belief that public art could inspire civic pride and a sense of common purpose. They were commissioned by the Treasury Department’s Section of Painting and Sculpture, which oversaw art for new federal buildings. They celebrate the Social Security Act of 1935, the landmark legislation guaranteeing benefits to retirees, the unemployed, and the disabled.

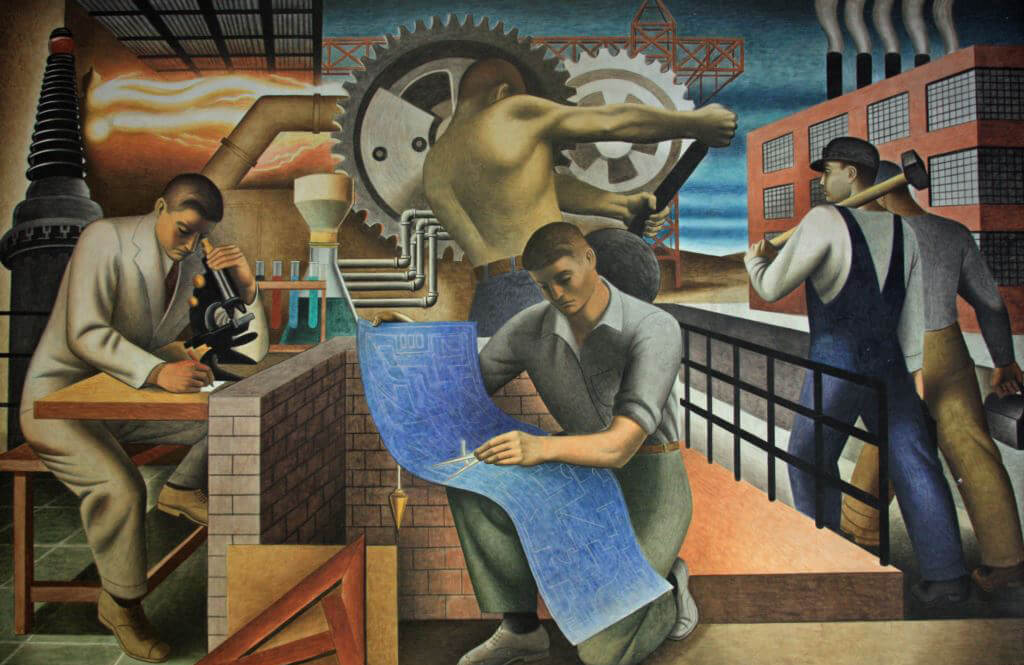

The murals came from some of the preeminent American artists of the 20th century. Ben Shahn, the subject of a recent critically acclaimed retrospective at the Jewish Museum in New York, painted a suite of murals contrasting social insecurity (child labor, old age, and unemployment) with the benefits of public works and secure jobs. Philip Guston, the subject of a major 2023 retrospective at the National Gallery of Art (located blocks away from the Cohen building), painted a scene of a family picnic on prosperous farmland. Seymour Fogel’s Wealth of the Nation crystallizes New Deal faith in the mutually reinforcing power of expert planning, scientific research, and manual labor. In each mural, the volumetric figures and dynamic compositions recall the artists’ close study of Mexican muralists and Renaissance masters.

The Security of the People by Seymour Fogel is among the murals inside the Cohen Building that speaks to the New Deal era and Social Security. (Carol M. Highsmith/ Library of Congress)

The Security of the People by Seymour Fogel is among the murals inside the Cohen Building that speaks to the New Deal era and Social Security. (Carol M. Highsmith/ Library of Congress)

Wealth of the Nation crystallizes New Deal faith in the mutually reinforcing power of expert planning, scientific research, and manual labor. (Voice of America/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain)

Wealth of the Nation crystallizes New Deal faith in the mutually reinforcing power of expert planning, scientific research, and manual labor. (Voice of America/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain)

The Cohen building has been justly called the “Sistine Chapel of the New Deal” for the aesthetic power and deeply felt humanism of its murals. Living New Deal founder and historian Gray Brechin coined the term. The murals are part of the building—the paint is bonded chemically to the walls—and cannot be removed except at significant cost and risk. The murals, like the building, embody what Roosevelt called the “cornerstone” of his administration—the Social Security Act, which worked to ensure cradle-to-grave safeguards for all Americans, regardless of wealth or status.

Preservation Acts

Americans have never consented to selling the Cohen Building—or any historic federal assets—to private interests. Laws and standards were enacted to protect such properties and their cultural resources. These include:

1949 — Creation of the GSA: The General Services Administration (GSA) was established and tasked with stewarding the nation’s federal buildings and public art, including the Wilbur J. Cohen Building.

1966 — National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA): Under this landmark legislation, and its longstanding enabling regulations established the Section 106 process, historically significant federal properties cannot be sold, altered, or demolished without consultation, public input, and development of formal agreements that either protect the resource or mitigate its loss.

1969 — National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA): NEPA reinforced the participatory public processes established by NHPA requiring federal agencies to consider actions holistically, weighing the public benefit of a proposed action against project impacts to both the human and natural environment. This process includes seeking both expert and public review of any project or sale affecting historic properties and to evaluate potential effects to historic buildings along with other potential related harms.

1978 — D.C. Historic Landmark and Historic District Protection Act: This local law protects designated historic properties through the D.C. permitting process. The Wilbur J. Cohen Building has been designated a D.C. landmark, granting it additional legal protections if it ever transfers from the federal ownership to the private sector.

2007 — National Register of Historic Places and D.C. Inventory of Historic Sites: The building’s inclusion on both registries formally recognized its architectural and cultural significance. While these listings do not guarantee protection, they affirm the need for a robust public process and our moral-civic duty to consider the highest standards of preservation and holding the building in public trust.

A Building in Peril

Sadly, the agencies that have occupied the Cohen Building have not had adequate resources for maintenance, and today it stands beside the National Mall practically empty and in disrepair. For this reason, and in recognition of its historic significance, the GSA had spent time completing a multi-year feasibility study for rehabilitating the building as a state of the art, and energy-efficient federal building. That plan was quietly shelved in January of 2025 and has not been released publicly. Instead of embracing expert recommendations and moving forward in restoring the Cohen Building this spring, the property has instead been included on the GSA’s newly invented “accelerated disposals” list.

At the same time, many of the GSA’s Fine Art and Historic Preservation subject matter experts were placed on administrative leave, leaving few staff to oversee its stewardship. This fall, news broke in coverage by Timothy Noah that the Cohen building’s destruction is a likely fait accompli due to a last-minute, unannounced provision inserted into an unrelated 2024 water bill.

A mural by Ben Shahn located in the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building (Carol M. Highsmith/ Library of Congress)

A mural by Ben Shahn located in the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building (Carol M. Highsmith/ Library of Congress)

Viable Alternatives

There are, however, viable alternatives. A public-private partnership, managed transparently by the GSA, could rehabilitate the Cohen Building while restoring public access to its artworks. Preservation covenants could ensure long-term protection, while adaptive reuse could revitalize the site as a museum, education center, or civic workspace. These solutions have been discussed and seriously considered in the recent past.

To prevent the destruction and loss of the Cohen Building and its irreplaceable murals, The Living New Deal Project (LND) is leading a public campaign and petition calling for transparency, preservation, and renewed public access. As a nonprofit that documents and advocates for New Deal–era art and public works, LND has been monitoring the situation with the GSA closely, sharing resources and advocacy materials, and submitted a formal request last month to participate in the GSA-led Section 106 consultation process, which will determine the fate of the Cohen Building and its art. LND was formally invited to participate once this process begins, but at this juncture, the accelerated timeline and level of transparency for how the disposal process will unfold is uncertain.

The Wilbur J. Cohen Building symbolizes creativity, resilience, and optimism—values as essential now as they were during the New Deal. Protecting this landmark honors the generation who built it and those who survived one of the most challenging periods in our history and thrived. In preserving the Cohen Building, we preserve that seed of hope in coming together and investing in shared culture and public space for generations yet to come.

Mary Okin is an art historian and the assistant director of the Living New Deal Project (LND). She heads LND’s Advocating for New Deal Art and New Deal Data Literacy initiatives and the campaign to save the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building.

John P. Murphy is the Philip and Lynn Straus curator of prints and drawings at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College. His survey, New Deal Art: Culture and Crisis in the Great Depression, was recently published by Thames & Hudson through its World of Art series.