MARQUETTE, Mich. — Suppose, at a time we’re so divided, that you’re interested in understanding split allegiances. And that one day you’re in a barber’s chair. And the barber is from Michigan. And the two of you are chatting about the Detroit Lions when he tells you, in fact, he doesn’t care about the Detroit Lions, because he’s a Green Bay Packers fan. Your head flinches, despite the hovering clippers, to look back at him.

But there’s an explanation. The barber hails from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, a place perpetually waiting for winter, where Yoopers, as locals are known, are fiercely proud, and protective, of their identities. When it comes to football, he explains, the U.P. is the ultimate house divided.

Lions fans. Packers fans.

They’re all up there, dotting a swath of land sometimes left off U.S. maps. It sits atop lower Michigan, for which it’s told to identify with, but where little is alike. Everyone in the U.P., or from the U.P., can and will recite to you the same stat: They account for 30 percent of the land mass of Michigan, but less than 3 percent of the population. When they’re omitted from a map, be it in print or a TV graphic or a refrigerator magnet, it’s not intentional. It’s worse than that. It’s an afterthought.

How many Yoopers are there? About 301,000, as of 2022. Lions and Packers fans, living together in the hinterlands. With a smattering of Vikings fans. And one or two Bears fans. (But no one likes them.)

How fun is that? Enough for an idea. And a trip. And a different view. As the Lions and Packers line up across from one another at Ford Field this Thanksgiving, it’s worth knowing where the rivalry really resides. You should know who’s up there.

First, like in any football story, you need a scouting report.

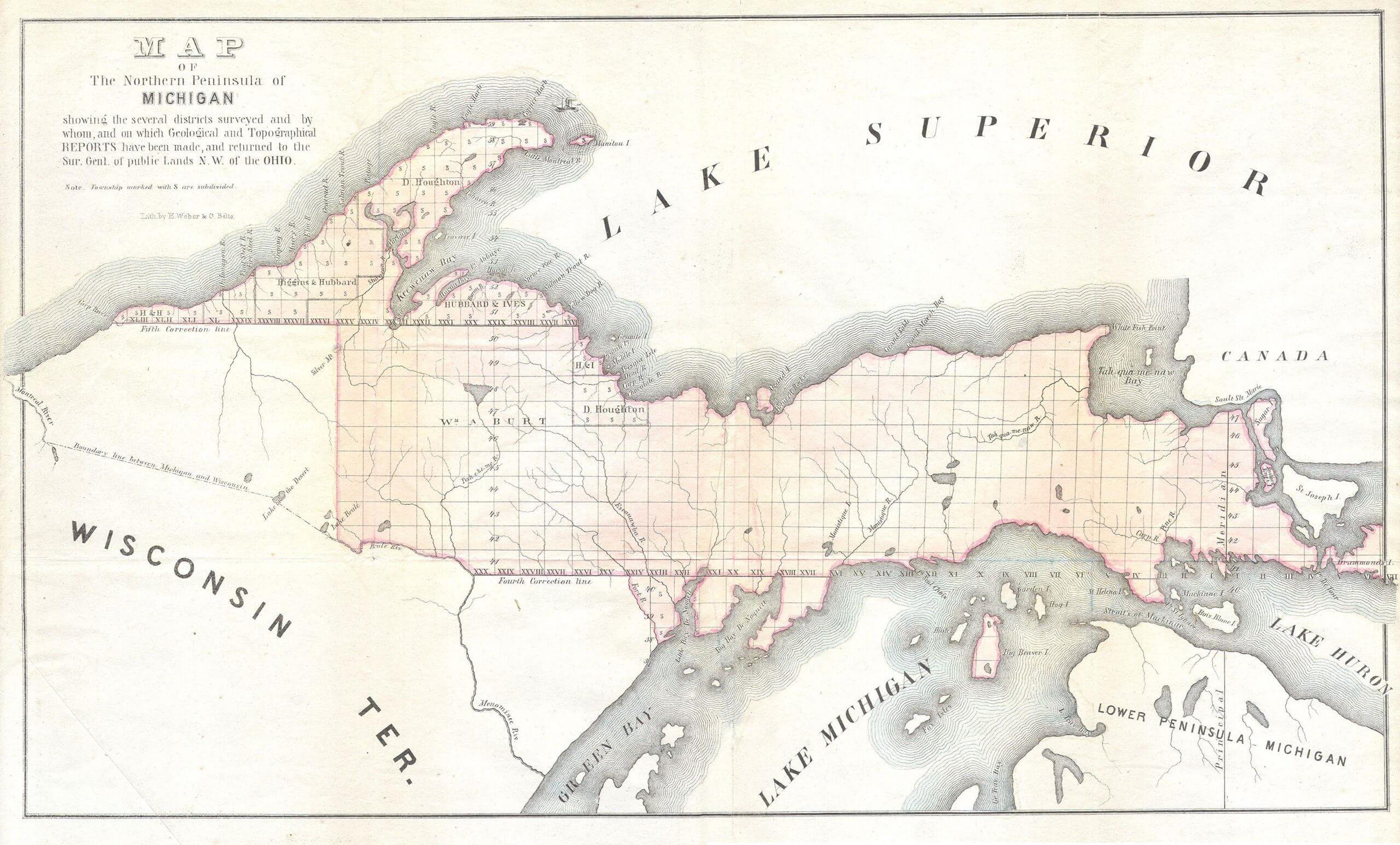

If a football coach were to break down the U.P., he’d do so first by wiping a chalkboard and drawing what looks like a rabbit in midflight, vaulting from right to left, across parts of three Great Lakes, its chin landing in Wisconsin, its ears jutting out into Lake Superior, and its hind legs stretching over Lake Michigan, over the lower peninsula and into Lake Huron.

Hand moving on the board, he’d diagram it. The western part? You have 200 miles of border with Wisconsin, cities like Ironwood, Iron River and Iron Mountain. The Keweenaw Peninsula juts upwards (that’s the ears). The middle part? That’s your economic and population hubs, cities like Marquette and Escanaba. Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore is where all the tourists go. Eastern side? That’s where the Mackinac Bridge connects lower Michigan to the U.P.; and to Tahquamenon Falls, one of the largest waterfalls east of the Mississippi River; and to Sault Ste. Marie, the U.P.’s second-largest city, where one of the world’s busiest lock systems connects Lake Huron and Lake Superior.

All told, the Upper Peninsula spans parts of two time zones (Central and Eastern) and measures about 375 miles from end to end, roughly the length of Kentucky.

“God’s country,” says Steve Mariucci, the former NFL coach, an Iron Mountain native.

All it cost was Toledo. The Upper Peninsula was part of the Wisconsin Territory until the federal government allotted it to Michigan in 1836. The deal was compensation to settle one of the lamest battles in American history. The Toledo War, as it’s called, was a boundary dispute between Michigan and Ohio over a 468-square-mile sliver of what’s now northern Ohio. With both states deploying militias to the Maume River, the conflict resulted in a few shots ringing out and the stabbing of an officer. (He survived.) Congress created a compromise that awarded the disputed land to Ohio, while apportioning Michigan with 16,378 square miles to its north. That’s about what this densely forested tract, and the people who lived on it, amounted to. A consolation prize.

Today, the area is larger than nine states.

“There’s a certain pride that comes with being a Yooper — the competitiveness, the isolation — and that’s something we all share,” Mariucci says. “But when it comes to football, the U.P. is definitely divided.”

An 1849 land survey map of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula

If you should find yourself crossing Lake Michigan, by plane or by bridge or by boat, it’s advised to call Walt Lindala first. For one, he can deliver an Upper Peninsula education in amazing detail. Two, you will likely be invited to drink beer.

Lindala is 58. He’s from Chassell, Mich., a town of 876 out in the western half of the U.P., what’s known as “copper country.” Lindala is a radio man. The realest kind. Big voice, barrel chest, dense gray goatee. He grew up dreaming of one day moving to Chicago to work for powerhouse WGN-AM. Except as years went by, and opportunities came to leave the U.P., he turned such offers down. Lindala has instead hosted morning radio shows across these parts of Michigan since the ’90s and worked as a broadcast news director.

He is also, you should know, a baptized Packers fan, one who will happily offer a history lesson.

“For people of a certain generation, like myself,” he says, “we had one choice, and that was the Green Bay Packers.”

It’s a Saturday afternoon at the U.P. Fall Beer Festival. Michigan’s many world-class brewers are assembled across 22 acres, just outside downtown Marquette, not far from the Lake Superior shoreline, where something out of “Transformers” appears to be climbing up on all fours. The Lower Harbor Ore Dock is a massive thing, concrete and steel with rows of timber pilings. It rose from the water in 1931, built to load iron ore from rail cars onto ore boats, sending shipments to the lower Great Lakes region for smelting and steel production. The dock was decommissioned in 1971.

Lindala grew up in the ’70s watching WLUC-TV Channel 6, the local CBS affiliate. Everyone did. Based in Marquette, WLUC broadcast NFL games from 170 miles away in Green Bay, instead of 450 miles away in Detroit. While the Lions’ glory days of the ’50s were hardly seen in these parts, the Packers’ championship teams of 1961, ’62, ’65, ’66, and ’67 flashed in living rooms. It was Packers players, not Lions, appearing on WLUC’s annual 24-hour marathon raising money for the U.P.’s March of Dimes. It was the Packers holding charity events and training camp games in the U.P., not the Lions. Green Bay, a town founded by fur traders with a football team marketed as meat packers, came to be seen by Yoopers as an extension of the U.P. It was, and is, their closest “big” city. Detroit? It’s closer to Louisville, Ky., and Davenport, Iowa, than it is to Marquette.

The Packers organization always understood its ties to the U.P. Six of the 22 players on the first Packers roster were from the U.P. Early schedules included games against alumni teams from the U.P. high schools. Ray Nitschke went hunting with friends in the U.P. When Packers ownership shares were first sold, representatives traveled outside Wisconsin, into the U.P., looking for any takers. Today, 2.45 percent of Packers shareholders and 2 percent of season ticket holders have Michigan addresses.

Things were made official in 1968. Vince Lombardi and the entire Packers organization were named honorary citizens. An actual state Senate resolution was issued: “The people of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, having solid affinity with the exploits of the Green Bay Packers and of their coach and general manager Vince Lombardi, exceed all bounds of enthusiasm for these cherished friends and their triumphant records.”

“That’s a kindred spirit that Detroit can’t exactly match,” Lindala says.

OK. Except, then why are these Lions fans here?

Like this woman standing in a line that’s crawling around the outside of Beer Fest. She’s wearing Lions-themed Chuck Taylors. You have to ask, why is she a Lions fan? She says her name is Jessica Hanley and she’s from Painesdale, an old mining town of less than 400 people along the coast of Houghton County.

“I live in Michigan, so I cheer for the Lions,” she says, eyebrow cocked, as if asked a dumb question by a very dumb man. “I know there are people up here who say that we’re closer to Green Bay. That has never made any sense to me.”

Hanley’s husband, Adam, is one of those people. He grew up farther west, on the Michigan side of the Michigan-Wisconsin border. Big Packers fan. When the two had a son, Oliver, a push-pull over his allegiance immediately began. Raise him as a Lions fan or a Packers fan? The two agreed that the winner of the teams’ next meeting would, in so many words, inherit their firstborn. Oliver was born in March 2017. On Nov. 6, 2017, the Lions beat the Packers, 30-17.

That’s some serious negotiating. What’s Jessica Hanley’s line of work?

“I’m the mayor.”

As in, she knows everyone? Or?

“Like, the actual mayor.”

Mayor Hanley, the second-term city commissioner of Marquette, has been eating forkfuls of crow all season. The Packers beat the Lions in this year’s season opener. Eight weeks later, she and Adam traveled downstate in early November for the Vikings-Lions game at Ford Field to celebrate her 40th birthday. The Lions lost. They’ll watch this week’s game rivalry rematch at Adam’s sister house in central Wisconsin. Packers Country. “And I will be decked out in my Lions gear,” Hanley says, “as will my child.”

Lions fans in the U.P. mostly stem from the eastern side. Sault Ste. Marie and St. Ignace received the TV feed of early Lions games and, since the 1957 completion of the Mackinac Bridge, have been far more connected to lower Michigan than the rest of the U.P. Then there are the transplants. Most downstaters who move north, whether for work or college (there are four state universities in the U.P.) or to get away from the world, arrive as Lions fans.

Twin brothers Bill and Pat Digneit were kids outside of Detroit when their family moved to the U.P. It was 2003 and Brett Favre and the Packers were stringing together division titles. Two years after the Lions went 0-16 in 2008, Aaron Rodgers and the Pack won Super Bowl XLV.

“It was so Packers-heavy here. Just brutal,” Bill Digneit says. “Those were some dark days. It was legitimately hard to find other Lions fans.”

But the Digneits grew older, came to identify as Yoopers, stayed for college, and opened a bar on the main stretch of downtown Marquette. Every February, the U.P. 200 — a 228-mile qualifying race for the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race — begins directly at their front door. Four years ago, when Iron River’s Nick Baumgartner (a Packers fan) returned from winning gold in the snowboard at the 2022 Beijing Olympics, the after-party was in their bar.

“A little different than metro Detroit, right?” Bill says.

But they haven’t let go of the Lions. Bill and Pat have four Lions season tickets and make “the pilgrimage down” for every game. Little by little, they’ve come to see a shift around them. More Lions fans. A byproduct of modern TV and a team that’s winning. The Lions have noticed, aiming some marketing efforts to the north. The team ships football and cheer equipment to two U.P. high schools and began a youth football camp last summer.

“Thank you, Ford family, for finally getting above the bridge,” Bill says.

Such efforts may not be necessary had things gone differently once upon a time. Many Lions-fan Yoopers theorize that, in an alternate universe, one that does not include former Detroit general manager Matt Millen assembling some truly heinous rosters, a whole generation of Yoopers would be Lions fans.

This is how the movie version would go: Mariucci is raised as a Packers fan. He attends Iron Mountain High School, where he meets a best friend, some kid named Tom Izzo, also a Packers fan. Mariucci is star quarterback for Northern Michigan’s 1975 Division II national championship football team. He grows up, gets into coaching, becomes the offensive guru behind some great Packers teams of the mid-’90s and becomes head coach in San Francisco. When a successful tenure with the 49ers comes undone after five years, Mariucci, the hottest available coaching candidate in football, agrees to return to his native Michigan to save the desperate, dispirited Lions. A successful tenure, cheerleaded by Izzo, would bring glory to the Lions, a first Super Bowl win to Detroit, and paint the U.P. in Honolulu Blue.

Or something like that.

Instead, Mariucci went 15-28 and was fired in 2005. Not only did his tenure not convert the U.P., but Mariucci, himself, remains a Packers fan. His family’s season tickets are in his name.

“Listen, even if things went differently when I was in Detroit, I wasn’t going to change the minds of Packers fans,” says Mariucci, now an NFL Network analyst. “They’re solid as a rock.”

Everyone is used to such truths. No one is willing to budge around here. That’s why, earlier this season, when the Lions and Packers opened the season at Lambeau, you could find everyone at Bill Digneit’s house for a seafood boil. Packers fans. Lions fans. Coming, going. All of them, proud misfits. Walt Lindala stopped by. So did Mayor Hanley.

They all, no matter what, have one thing in common.

When the Mackinac Bridge first opened, many feared the U.P. would cease to maintain its singular identity. “It has, in fact, been the opposite,” says Dan Truckey, director of the U.P. Heritage Center at Northern Michigan University.

Early this semester, Dan Truckey, the director of the U.P. Heritage Center at Northern Michigan University, began his class on the U.P. and popular culture with a visual. The palm of his hand.

The mitten. The most commonly known version of Michigan. How most see the state. How non-Detroiters identify where they’re from — point to the index finger for Alpena, or the middle of the pinky for Ludington, or the crease between the thumb and the palm for Bay City. A perfect rendering of how so many in the U.P. feel. Nonexistent, discarded, forgotten.

“There’s both a physical separation and cultural separation,” Truckey says.

Separation, you learn in the U.P., has a lot in common with isolation, and, to hear Truckey explain things, such sentiment runs in the water.

Fifty years ago, as the United States readied for the 200th anniversary of revolutionary victory, citizens in the U.P. considered a different rebellion. It was early November 1975 and secession was on the ballot.

Voters in Marquette and Iron Mountain, then the U.P.’s two largest cities, weighed a referendum asking if the region should consider a split from Michigan and a pursuit of individual statehood. The proposed 51st state would be known as Superior, a nod to one of the three Great Lakes bordering the peninsula and the citizens’ embrace of their remote station in the world. The whole idea, in all its audacity, was met with eye-rolling by outsiders. In the U.P., though, the vote was part of a common cross-examination of an existential question.

Who are they?

The U.P. was first settled by Paleo-Indians, the first human inhabitants of the New World. Later came French Canadians, and Cornish, and Italians, and Scandinavians. Finnish miners settled en masse in the 1860s, filling jobs and creating what is today the densest population of Finns found anywhere in the U.S.

“Interesting dynamics,” Truckey says. “People in the U.P. identify with the U.P. We don’t really identify with Wisconsin or lower Michigan. If you ask someone in the U.P., what are you? They’re more likely to say ‘Yooper’ than ‘American’ or ‘Michigander.’”

That 1975 vote fell well short of passing: 3,442 against, 1,515 in favor. There are feelings, and then there are realities. Even while often feeling like territorial subjects to downstate interests, the economic impracticalities of going at it alone have always been mostly understood. While, yes, the U.P. is larger than Maryland, there are also fewer people than in Durham, N.C.

Today, U.P. sovereignty is seen only in its version of the map. The outline of the U.P., alone, is everywhere — bumper stickers, wood carvings, bathroom stalls, jewelry, tattoos on forearms.

“When the Mackinac Bridge first opened, many feared the U.P. would cease to maintain its singular identity and start to blend in culturally with the lower peninsula,” Truckey says. “But it has, in fact, been the opposite. If anything, the Yooper identity has strengthened since that time. There’s even more of a sense of identity of place, culture and way of life.”

Such things aren’t free of complications. Political fractures, addiction, racism, economic hardships, climate concerns — such things exist here as they do everywhere. But few things in the world dictate how we see ourselves as much as where we live. And in the U.P., where modern life can feel just a step behind the times, that sense of place is ever-present.

As for Truckey, he’s pulling for Green Bay this week. He was born in lower Michigan to parents both originally from the U.P. They moved back when he was 11. So he’s a Packers fan, but his three brothers are Lions fans.

“We don’t have much in common,” he says.

This winter, at various times, and in varying amounts, the Upper Peninsula will receive between 200 and 300 inches of snow. But today is a gleaming fall afternoon and there, across the Beer Festival, beyond a sea of flannels, shining in the sun, is perhaps the answer to the ultimate question.

The tent reads: 51st State Brewing Company.

Jeff Brickey has been in business for eight years and brews a mean porter. He, personally, appears to have awarded the Upper Peninsula statehood, so maybe he can determine the U.P.’s allegiance.

Before opening his brewery, Brickey worked as a manager at an iron foundry on the Menominee River, where the “twin cities” of Menominee, Mich., and Marinette, Wis., stare across at each other. This is, perhaps, the nexus of the Packers-Lions rivalry. Crossing the bridge from Marinette to Menominee, you’ll find a sign reading, “Where the best of Michigan begins.” Stopping in the small welcome center, you’ll meet a cheery woman who loves her state, but says she’s a diehard Packers fan. Her daughter got married at Lambeau Field.

Brickey and his wife, Victoria, raised their children on the Wisconsin side of the Menominee, in Marinette. Those children grew up to be Packers fans.

Jeff Brickey, however, grew up in Southgate, Mich., downriver from Detroit, taking the bus to Tiger Stadium to watch the Lions play in the ’60s and ’70s.

So when it comes to deciding the U.P.’s official team, there isn’t much question.

“The Lions, of course,” he says.

Does it bother him that he’s outnumbered? That his own children are sickened by his team?

“Doesn’t bother me one bit,” Jeff Brickey says, pushing up his shoulders.

Spoken like a true Yooper. There’s a word you see and hear often in the U.P. — “sisu.” It’s Finnish, and everyone has his or her own translation. It means, essentially, unending determination. As in, it takes sisu to live in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Time has proven as much. The U.P. is dotted with ghost towns, where mining or forestry operations once boomed, where abandoned train tracks now run from nowhere to nowhere.

Today’s primary economic engine in the U.P.? It rings hollow for most who live here. Tourism. Mayor Hanley is concerned that the area’s children will have to look elsewhere for jobs. Walt Lindala is worried what industries will realistically exist in the next 15-20 years. Mariucci, even while living across the country, bemoans the sharply declining populations and dropping birth rates in the U.P.’s rural areas.

But that’s real life, and there’s no room at the Thanksgiving table for that. This week is about the Lions, and the Packers, and gaining another inch in a divided land. That, and bragging rights. And playoff positioning. And, of course, shoveling. The U.P.’s forecast this Thanksgiving? A blizzard.