Will artificial intelligence solve art history’s many mysteries and disputes? Earlier this week it was reported that a Swiss art verification company had used AI software to determine that Johannes Vermeer’s long disputed Girl with a Flute was indeed the work of the 17th-century master from Delft. The computer said yes — even though the painting’s authenticity is questioned by the museum that owns it, the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

I have spent much of the past several years thinking and writing about Vermeer, and left Girl with a Flute out of my recent book precisely because it is of questionable quality. But on balance I agree with AI. Girl with a Flute was borrowed by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam for its 2023 Vermeer exhibition and in that context looked every inch the real deal, albeit not one of his masterpieces. The infelicities in its execution can be explained by the fact that it appears never to have been entirely finished. The more eye-catchingly clumsy elements, such as its botched chiaroscuro, were probably the work of a later restorer trying to make it look more resolved than it was. Old pictures often bear such messy traces of their own past.

Making allowance for that, a great deal else in Girl with a Flute seems inimitably Vermeer: the pointillist highlights on the sitter’s costume, especially the ruffs of the sleeves; the soft focus in which the lion’s head finial and the studs of the leather-backed chair have been painted. It is hard to think of anyone else who could have painted such beguiling details. None of Vermeer’s contemporaries — not Carel Fabritius or Gerard ter Borch, who occasionally came close — created anything like it.

• Whatever happened to art on TV? Today we get bum jokes

AI will have made its verdict after comparing a large fixed data set of Vermeer’s work and that of other Dutch 17th-century artists. Analysing data with dispassion is what it does best. In that respect it can be helpful, especially when presumed experts get so bound up in the subtleties of their own ideas that they can no longer see the wood for the trees.

This seems to be exactly what happened at the National Gallery of Art, where researchers in the conservation department analysed the picture during the Covid pandemic and cast doubt on its authorship. They became so troubled by the parts of it that seemed “awkward” or “heavy-handed” that they felt compelled to find an alternative explanation — that it was painted not by Vermeer but by an artist close to him, someone who had seen the master at work and was familiar with his methods but had not quite mastered them. In the blink of an eye Vermeer had acquired a studio assistant, one among several perhaps, helping him to fulfil the many commissions that came his way.

It is a neat enough theory but one that is starkly contradicted by the many facts about Vermeer that have been recovered from the archives of 17th-century Holland. We know, for example, that Vermeer painted very few pictures, probably fewer than 40, and that nearly all were done for a single family in Delft. We know that he was almost completely unknown outside a small circle of people in Delft, Rotterdam and Amsterdam and that the demand for his work was therefore extremely limited. All the evidence suggests that he worked alone and slowly, taking such great pains over the creation of major pictures such as the View of Delft that each one may have occupied him for six months at a time.

My own research has revealed that most of Vermeer’s work is animated by deep religious belief and he seems to have painted with the meditative intensity of one praying. The idea that he might have run a busy studio, painting for gain and fame, and employing assistants in the manner of Rubens, is pure fantasy.

• The Upside-Down World by Benjamin Moser review — a golden age? Not for the poor old artists

And here you have both the strengths and the weaknesses of AI as a tool for art historical research. While I believe AI is right to attribute Girl with a Flute to Vermeer, its conclusions will carry little weight with researchers in Washington. They know perfectly well that statistical analysis will inevitably give the picture to Vermeer and they have already built that into their contrarian reasoning — that here is the work of someone who knew how to mimic all his visual tricks.

AI can ask humans to think again. It can remind them just how strongly the visual data argues for Vermeer’s authorship. But it cannot prove beyond reasonable doubt that the researchers are wrong. In other words its conclusions are helpful but not decisive. Other kinds of data — in this case our archival knowledge of Vermeer and his milieu — are necessary to clinch the case.

Vermeer was so obscure in his own time, and for two centuries after his death, that barely any copies of his work have survived, let alone studio versions. If his mythical assistant did exist, where on earth are all the other pictures he (or she) must have painted? This is not a question AI would think to ask, and one that it would be unable to answer.

The fact is that Vermeer was unvenerated, unemulated and hardly ever copied. The only earlyish copy of a Vermeer I can think of is the truly dreadful Philadelphia version of The Guitar Player recently lent to Kenwood House, which was clearly daubed by some anonymous fifth-rater between 50 and 150 years after the painter’s death.

The “truly dreadful“ Philadelphia version of Vermeer’s The Guitar Player

ENGLISH HERITAGE

Openness, creative common sense and an element of imagination not possessed by present incarnations of AI are fundamental to understanding and correctly attributing works of art. AI is good at analysing artists’ signatures, although not strikingly better than human experts. It is particularly good at discovering an artist’s tics or mannerisms across a wide range of work, then looking for evidence of the same in a disputed picture. The results are rarely conclusive, expressed as they mostly are in a percentage of probability that such and such a painting is or is not by such and such an artist, but they can play a part in helping art historians decide if they are on the right track.

AI’s judgments appear to be more questionable when it comes to more linear artists such as Dürer, and more sound when applied to so-called “painterly” artists such as Titian, perhaps because it has more data to work with. In 2023 the same AI company that verified Vermeer’s Girl with a Flute determined that the Flaget Madonna, discovered in an English antiques shop 30 years ago, was by the Renaissance master Raphael. It can struggle with work that that has been badly damaged, or an artist who was very varied in their style or even quality: even masters had off days.

Titian’s Portrait of a Young Man (c 1515-1520)

ALAMY

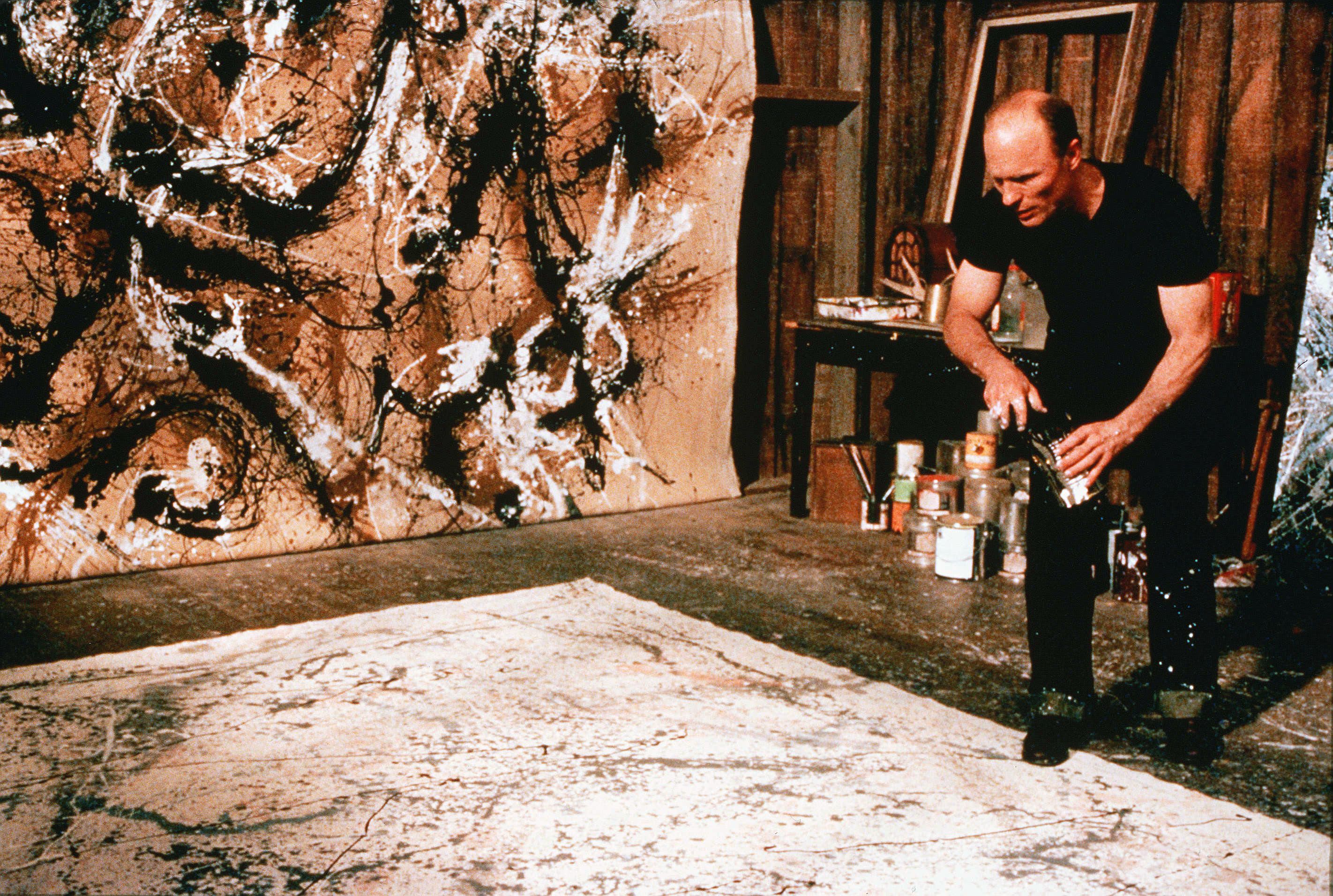

Ed Harris creates his own Jackson Pollock in the 2000 biopic

SHUTTERSTOCK

Last year a professor at the University of Oregon trained AI to tell the difference between real and fake Jackson Pollocks with 99 per cent accuracy: because there were so many copies — including by the actor Ed Harris, as part of his process for playing him in Pollock (2000) — they had a large dataset of fakes to measure the real drip art against. I am thinking of using AI myself to test an exciting new discovery — a possible sketch for the Mona Lisa by Leonardo’s own hand. I am not a convert but willing to learn from it what I can.

Computers work most effectively within closed systems — for example a game of chess — within which they can exercise their vast capacities for mathematical projection. But works of art and those who create them exist within the most open of all imaginable systems, namely the history of the world. This is not something AI can begin to navigate, with its millions of competing perspectives and subplots.

• Thunderclap by Laura Cumming review — the mystery of Carel Fabritius, artistic genius

The keys to understanding a particular picture often have to be intuited. All the bits and pieces of the past need be considered. You might find a clue in Leonardo’s notebooks or Vincent van Gogh’s letters — or even something as dry as a 17th-century marriage certificate related to someone related to the artist.

My own transformative realisation, that Vermeer was first and foremost a religious artist, came to me while poring over the name of his father’s preacher, as recorded in just such a document. Art and artists are part of time, life and the world, just as we are, and can only be truly experienced in the hearts and souls of other human beings. Seeing them as datasets teaches us something — but that something will only ever be a tiny part of the whole.

Vermeer: A Life Lost and Found by Andrew Graham-Dixon (Allen Lane £30 pp416). To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members