Photo: Neon/Everett Collection

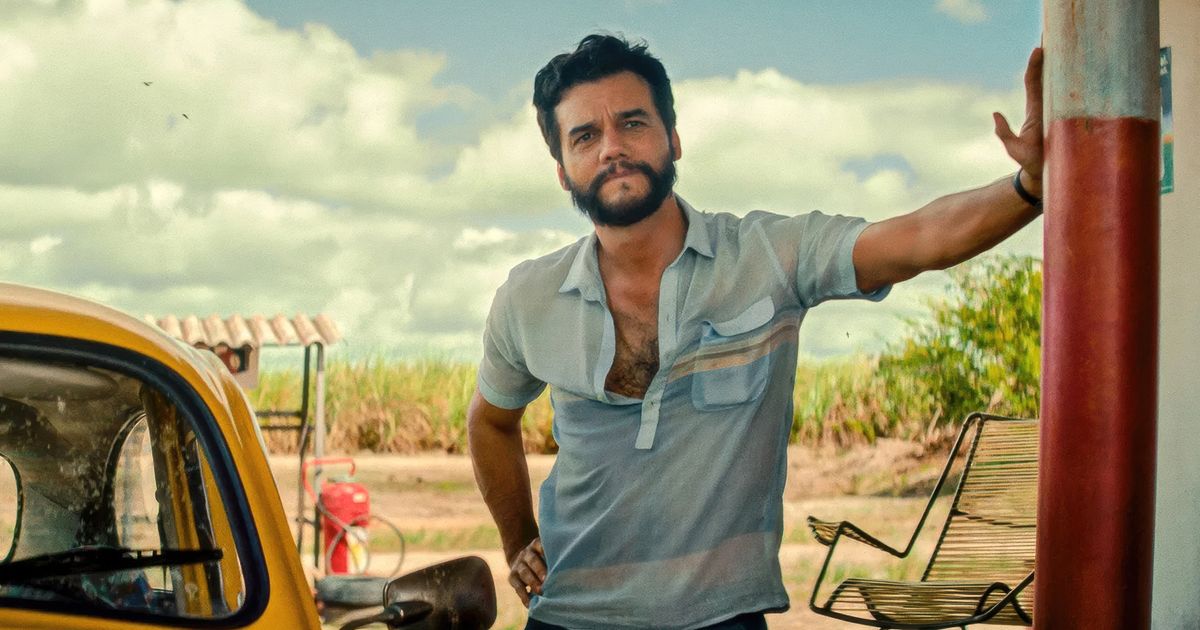

Armando Solimões, the mournful-eyed central character played by Wagner Moura in The Secret Agent, isn’t a government operative, despite the title of the film. He also isn’t undercover, exactly, though for most of the first half of the film, the terrific latest from Kleber Mendonça Filho, he goes by the alias of Marcelo Alves. When Armando first rolls up to a gas station on the outskirts of his hometown of Recife in his yolk-yellow Volkswagen Beetle with days-on-the-road scruff, he has an air of watchfulness that suggests there’s more to him than initially meets the eye. Then again, it’s 1977 in Brazil, and a degree of caution is warranted from everyone, given that the country is over a decade into a military dictatorship whose effects have seeped into many aspects of day-to-day life. We get a sense of that destabilization in the opening scene, when Armando notices a corpse moldering a dozen or so yards from the gas pump — a would-be thief, the attendant tells him, whose death the police were notified about days ago. But when a pair of cops do finally pull up while the men are talking, it’s not to take care of the body but to shake down this passerby, taking the remainder of his pack of cigarettes when he turns out to be out of cash.

The Secret Agent is Moura’s first Portuguese-language role in years, and he infuses Armando with the ragged gravitas of a New Hollywood star while embodying the specifics of his time and place so intensely he could be an old Polaroid come to life. The whole film is shot in the rich tones of an exhumed photo album for reasons that start to become clear only halfway through, when it takes an abrupt jump forward to a present day in which researchers at a university are working through archival material. Armando is not just a man who ran afoul of an oligarch with ties to the regime — he’s a half-forgotten memory himself, someone that, we start to understand, we’re getting a more intimate understanding of than the people he left behind. While the timing is in no way intentional, Armando emerges as a melancholy South American counterpart to Leonardo DiCaprio’s Bob Ferguson in One Battle After Another — another single dad who’s been forced into hiding after taking a stand, who finds sanctuary in a community of outsiders and rebels, and who wants only to connect to his kid, an impish boy named Fernando who’s become obsessed with sharks, thanks to the marketing for Jaws.

The key differences between Bob and Armando, beyond Armando being a lot less of a clown, are the perspective from which they’re seen and the degree to which they chose the fight they’ve found themselves in. If Paul Thomas Anderson’s film comes from the point of view of a regretful Gen-Xer looking ahead to the world and the struggles his teenage daughter is inheriting, The Secret Agent very much looks back, as though aiming to use cinema to open a portal into a past that’s been obscured under scar tissue or paved over and rebuilt. (The film has all sorts of links to Filho’s last one, the personal doc Pictures of Ghosts, including a reference to a movie palace that has been transformed into a blood bank.) Time has a way of leaving those who’ve endured trauma reluctant to unearth the past and afraid to talk about wrongs left unaddressed. The Secret Agent is an act of dual challenge to this erasure. The film itself is presented as a sort of séance for Armando, whose fate is unknown for a long time but who remains in traces on old audio cassettes recorded by a member of an activist group trying to help him flee the country. But Armando himself doesn’t want to leave without securing his own artifact from the past — the file for the identity card his own teen mother applied for years earlier, quite possibly the only trace he’ll find that she ever existed.

Whoever gets to write history gets to define it, while everyone else vanishes alongside living memory. But if The Secret Agent is as complex and rewarding as a taste from a dusty bottle of wine, it’s also part of an ongoing consideration in this year’s releases about what it means to be part of a resistance, one that includes not just Anderson’s action drama but also Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just an Accident and Julia Loktev’s Russian journalist documentary My Undesirable Friends. Some of the characters in the Recife apartment complex where Armando hides out, like the delightfully salty matriarch Doña Sebastiana (Tânia Maria, one of several cast members who also appeared in Bacurau), are former revolutionaries. But others are united by simply being on the run, fleeing bad domestic situations or, in the case of the couple from Angola, danger in their homelands. Armando himself is an inadvertent insurgent, still furious that his life is in danger because he had the gall to stand up to the preening businessman who shut down his university departments. But you don’t have to be an active protester to find yourself on the wrong side of authoritarianism; you need only cross someone favored by those in power. In The Secret Agent, there’s no line between a refugee and being part of a resistance movement — there’s only the state and the people who’ve been designated its enemies.