The daunting question faced for years now by a small farming valley in Mendocino County is where it will turn to for irrigation water once the Lake County dam that impounds its main source, Lake Pillsbury, comes down.

Owner Pacific Gas & Electric Co. is seeking federal approval to decommission the dam and the connected hydropower project that for more than a century has funneled Eel River flows through a mountain tunnel into canals that feed Potter Valley, and eventually emptying into the Russian River, boosting its supplies for downstream cities and farms.

As expected, once Scott Dam is gone along with its downstream waterworks — a removal project PG&E estimates to cost $500 million — Potter Valley growers, ranchers and residents worry they could be left high and dry.

Officials in Mendocino and Sonoma counties have been working on backup storage options to avoid that scenario and sustain the valley’s $35 million agricultural output, the lifeblood of its rural community.

At a Monday meeting in Ukiah, they unveiled some of the early concepts, little more at this stage than just “cartoon drawings,” as Tom Johnson, engineering consultant with the Mendocino County Inland Water and Power Commission, or IWPC, acknowledged at the meeting.

The federal decommissioning process is not a fast one, and any dam removal project, should it be approved, is likely years away.

But building new water storage in California is not easy or cheap.

“We need to figure out storage before Scott Dam goes away and before we have little water,” said Scott Shapiro, legal counsel with the water and power commission, the joint powers entity that oversees water use and quality in the Eel and Russian River watersheds.

The infrastructure at issue actually consists of two dams — Scott and the smaller Cape Horn Dam at the foot of a holding reservoir downstream — plus the idled 117-year-old powerhouse fed by the diversion tunnel between the two watersheds. The shorthand name for it all is the Potter Valley Project, and PG&E began taking steps in 2019 to abandon it.

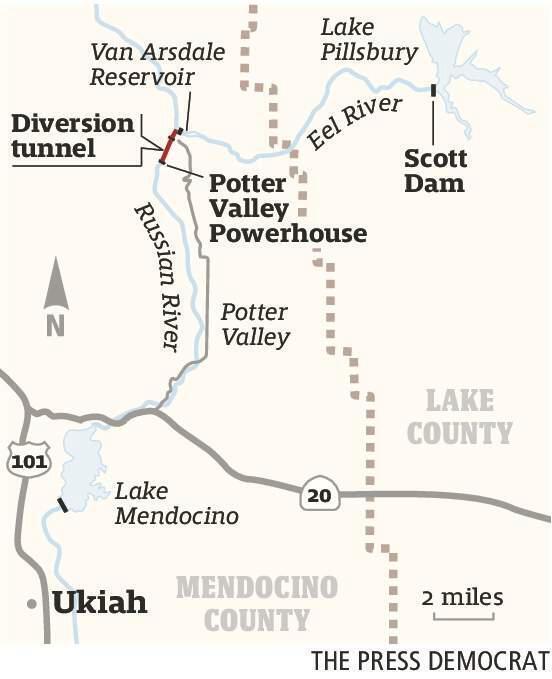

Press Democrat

This diagram shows how water from Lake Pillsbury, through Scott Dam, now flows downstream toward Cape Horn Dam and Van Arsdale Reservoir, through a tunnel to the Potter Valley Powerhouse into the East Fork of the Russian River, then into Lake Mendocino. (Press Democrat)

Under a historic agreement reached early this year involving tribes, local governments, environmental interests and water entities, both dams are set to come down — in what would be the nation’s next big dam removal project, freeing up the headwaters of California’s third longest river to help revive its troubled salmon and steelhead trout runs.

Officials said this week that any demolition date is likely at least six years out.

Some area residents and dam removal opponents, including many Lake Pillsbury property owners, are determined to halt that work and reverse those plans. They continue to press the Trump administration to intervene and are holding a 9 a.m. campaign event Saturday at the high school in Cloverdale.

Todd Lands, the city’s mayor and a candidate for Sonoma County supervisor next year, has emerged as a leading figure in that pressure campaign.

“Let your voice be heard! We will be there to answer questions about how this affects everyone in our region!” Lands said in a Facebook post.

How to comment on PG&E’s application to decommission the Potter Valley project

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC, is accepting public comment on PG&E’s application to decommission the Scott and Cape Horn dams, and cease all operations at the Potter Valley hydroelectric plant in Mendocino County.

Comments are due by 2 p.m. (PST) Monday, Dec. 1 by 2 p.m. Once an individual or stakeholder submits a comment, they will receive updates throughout the decommission application process. Here are the steps to submit a comment:

Use the FERC website to send comments electronically.

First, follow the instructions on the ‘FERC Online’ site, to authorize a comment.

After clicking, ‘authorize,’ FERC will send an email; check your email for your eComment link.

Follow the eComment link.

Search for docket number (P-77-332) and select the blue + symbol

Enter your comments in the text box, and select “Send Comment.”

Comments can also be sent through the mail. Letters must be postmarked by Dec. 1. Address comments to:

Debbie-Anne A. Reese, Secretary

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

888 First Street NE, Room 1A

Washington DC, 20426

Others say they see the writing on the wall and that such efforts are a waste of time and energy.

“We need to support, not prevent the decommissioning … to ensure diversions continue,” Shapiro, the water commission attorney, said during the Monday workshop at the Ukiah Valley Conference Center.

New plumbing to link watersheds

About 100 people attended the meeting, and dozens more followed the discussion online.

Johnson, the water commission engineer, explained some of the work already going into how to capture and sustain the supplemental flows that come from the Eel River into the Russian River system, which provides water to 700,000 residents, plus vineyards, farms and ranches, stretching from Ukiah to northern Marin County.

Over the past two years, officials from the IWPC, Sonoma Water, the region’s dominant water wholesaler, as well as the Eel Russian Project Authority — the joint powers entity that will be responsible for managing future water diversions — have forged ahead with planning for a future without the dams.

Doing so requires two major efforts: ensuring diversions continue as called for under the historic pact once the Cape Horn Dam is gone; and adding enough storage options for that diverted water to make up for the loss of storage once Scott Dam is torn down and Lake Pillsbury is drained.

Eel-Russian Project Authority

Rendering of a proposed pump station facility to permit diversion of Eel River water into the Russian River once PG&E removes the Cape Horn Dam at Van Arsdale Reservoir. (Eel-Russian Project Authority)

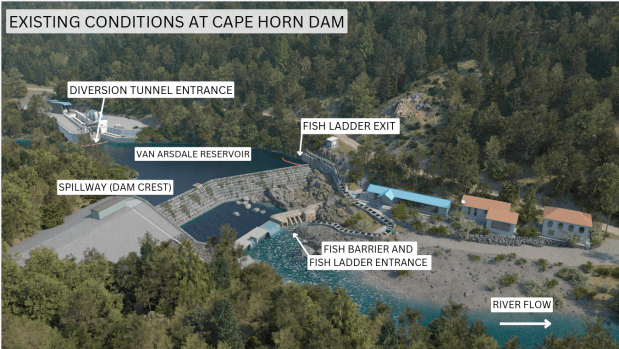

An infographic by Sonoma Water shows the existing conditions at Cape Horn Dam, part of the Potter Valley hydroelectric power plant slated for decommissioning, in Mendocino County. (Sonoma Water)

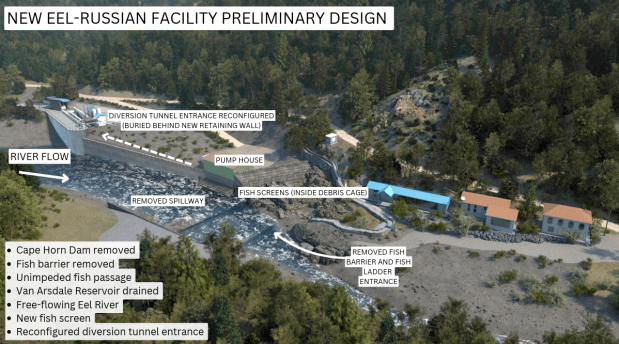

An infographic showing the preliminary design for the New Eel Russian Facility, or NERF, which would divert water from the Eel River to the East Fork of the Russian River once Cape Horn Dam is removed. The dam is part of the Potter Valley hydroelectric power plant slated for decommissioning, in Mendocino County. (Sonoma Water)

Christopher Chung/ The Press Democrat

Water from the Eel River collects at the Van Arsdale Reservoir and flows over the Cape Horn Dam. A percentage of the water is redirected through a diversion tunnel, at the building in the background, to the Potter Valley Powerhouse and east fork of the Russian River.(Christopher Chung/ The Press Democrat)

The Van Arsdale Dam and reservoir on the Eel River.

Show Caption

Eel-Russian Project Authority

1 of 5

Rendering of a proposed pump station facility to permit diversion of Eel River water into the Russian River once PG&E removes the Cape Horn Dam at Van Arsdale Reservoir. (Eel-Russian Project Authority)

The first effort, the new diversion plumbing and framework for when flows can be pulled from the Eel into the Russian River, is further along. Sonoma Water expects to construct a new diversion tunnel as Cape Horn Dam comes down; the current tunnel will be made unusable at that time.

“We are trying to coordinate with PG&E,” said Sonoma Water Environmental Resources Manager David Manning. “We don’t want to have a gap in time where we can’t divert. We are very aware that any gap in time is akin to a ‘no diversion’ scenario. We want to minimize that.”

The diversions would occur only during high-flow periods, and max out at roughly 30,000 acre-feet annually. (An acre-foot is equivalent to the amount of water needed to flood most of a football field one foot deep, and can supply the needs of three water-efficient households for a year.)

“The pumping rules lay out a schedule of how the flow can be diverted seasonally to protect the fish,” Manning said.

That new framework has alarmed farmers and residents along the upper Russian River, who are used to relying on year-round diversions from the Eel, and at historically higher annual average volumes.

Manning, a longtime Sonoma Water official and fisheries biologist who now leads the newly formed Eel-Russian Project Authority, said while he understands concerns about the loss of dry-season diversions, the new waterworks and rules governing how they are used are the best option for a future without PG&E’s equipment in place.

Without the new waterworks, diversions would be “about half of what they currently are,” he said. “Diversions haven’t been that low except in the very depths of the worst droughts.”

Many storage options to replace one

Going forward, because year-round Eel River diversions are set to be phased out, expanded water storage is seen as critical by most interests who rely on those flows in Potter Valley and the upper Russian River watershed.

Engineering teams, including outside experts hired by the IWPC, are in the early stages of exploring a range of options for Potter Valley, where irrigation supports about 2,300 acres of cropland.

The engineers have pinpointed six options so far to replace between 30,000 and 60,000 acre-feet of water typically held in Lake Pillsbury.

While none of the proposed options are a “silver bullet,” said Johnson, some could store more water than Potter Valley Irrigation District customers could use, providing benefits for customers downstream.

Kent Porter / The Press Democrat

The north end of Potter Valley in Mendocino County basks in sunlight on May 14, 2025. (Kent Porter / The Press Democrat)

One concept — an enlarged network of storage ponds — is already in place in Potter Valley. Farmers have built 55 water storage ponds, capable of holding 775 acre-feet of water over 125 acres of land.

Johnson estimates the valley needs at least 5,000 acre-feet of additional storage capacity. To get there, storage ponds would need to cover another 500 acres, eventually accounting for 10% of valley floor space.

The estimated cost for additional storage ponds ranges from $15 million to $28 million, which does not account for the cost of the distribution systems eventually needed to fill and drain the ponds.

Another potential project for the valley would rely on storing more water underground in a method known as groundwater recharge. The number of wells in the valley would grow about five-fold to tap into the 3,500 acre feet of groundwater made available each year.

That project could cost between $19 million and $22 million, plus the expense of more pipes to expand what’s already in place, Johnson said.

While grants and federal funding are available for both projects, much of the cost would likely go back to Potter Valley Irrigation District ratepayers. Potter Valley irrigators pay $35 (general delivery) per acre foot per year for water or $125 to $175 for so-called garden rate users, according to district documents.

New dams to offset lost ones?

Another option floated Monday is adding new storage — in the form of dams — along tributaries.

Two streams within Potter Valley, Busch and Boyes creeks, could be candidates, according to Johnson, who said they would add storage equivalent to up to 25,000 acre feet.

Another idea would involve carving a small reservoir, impounded by a new dam in the lower portion of Potter Valley, Johnson said. The reservoir could span about 60 to 640 acres, he said.

Still, both options involving dams would be costly — running between $115 and $250 million — and highly difficult to permit, he added.

Banking on Lake Mendocino

Another option, Johnson said, would be to build a pump station and 10-mile pipeline extending north from Lake Mendocino to Potter Valley. The pipe project could be designed to divert 10,000 acre feet of water from Lake Mendocino to Potter Valley each year.

Such projects are fairly straightforward from an engineering standpoint — Shapiro pointed to recycled water pipelines built in cities like Eureka and Healdsburg — but water rights could prove a sticking point.

“All the current storage is fully subscribed,” Johnson said of the supplies captured by Lake Mendocino. “That’s a big problem.”

Beth Schlanker/The Press Democrat

Visitors walk across the top of Coyote Valley Dam as water is released down the spillway at Lake Mendocino near Ukiah, Calif., Monday, January 16, 2023. (Beth Schlanker/The Press Democrat)

That hurdle could be addressed by another concept already under federal study: raising the height of Coyote Dam, which impounds Lake Mendocino. That would allow the reservoir to store more supplies, possibly equivalent to the amount needed and controlled by Potter Valley irrigators.

Key questions and concerns

Monday’s workshop prompted several overriding questions: How do such concepts move from the drawing board to execution? Who pays for them? And who stands to lose land, should that come to pass?

Those unknowns spurred some in the audience to speak out, pressing key officials with their concerns.

Johnson acknowledged the uncertainties still dominating the discussion. But, he added, now is the time to “prioritize what is needed.”

Amie Windsor is the Community Journalism Team Lead with The Press Democrat. She can be reached at amie.windsor@pressdemocrat.com or 707-521-5218.