For example, someone living in an apartment building with a package drop-off area may avoid using mail order because their package could get stolen. Someone who lacks internet access or doesn’t speak English may struggle to order prescriptions. Someone with strep throat can’t wait three days for an antibiotic to arrive.

Get The Gavel

A weekly SCOTUS explainer newsletter by columnist Kimberly Atkins Stohr.

A 2019 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that adults over 50 taking cardiovascular medications were less likely to take their medication consistently after the pharmacy where they previously filled a prescription closed. That drop persisted a year after the closure. A 2024 JAMA study in Colorado similarly found that patients filled fewer prescriptions for anticonvulsant medications — which are prescribed to treat epilepsy, some types of chronic pain, and other illnesses — after their pharmacy closed.

Additionally, amid a shortage of primary care doctors, many people rely on pharmacies for vaccinations. For older residents with Medicare Part D insurance plans, physicians may encourage patients to get vaccinated at a pharmacy because it simplifies billing.

In Massachusetts, pharmacists can also prescribe birth control and order medication-related lab tests.

“They are central health hubs and are arguably one of the most accessible health care providers,” said Kaley Hayes, associate director of Pharmacoepidemiology at Brown University’s Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research. When pharmacies close, Hayes said, “It’s taking another health care provider out of the equation.”

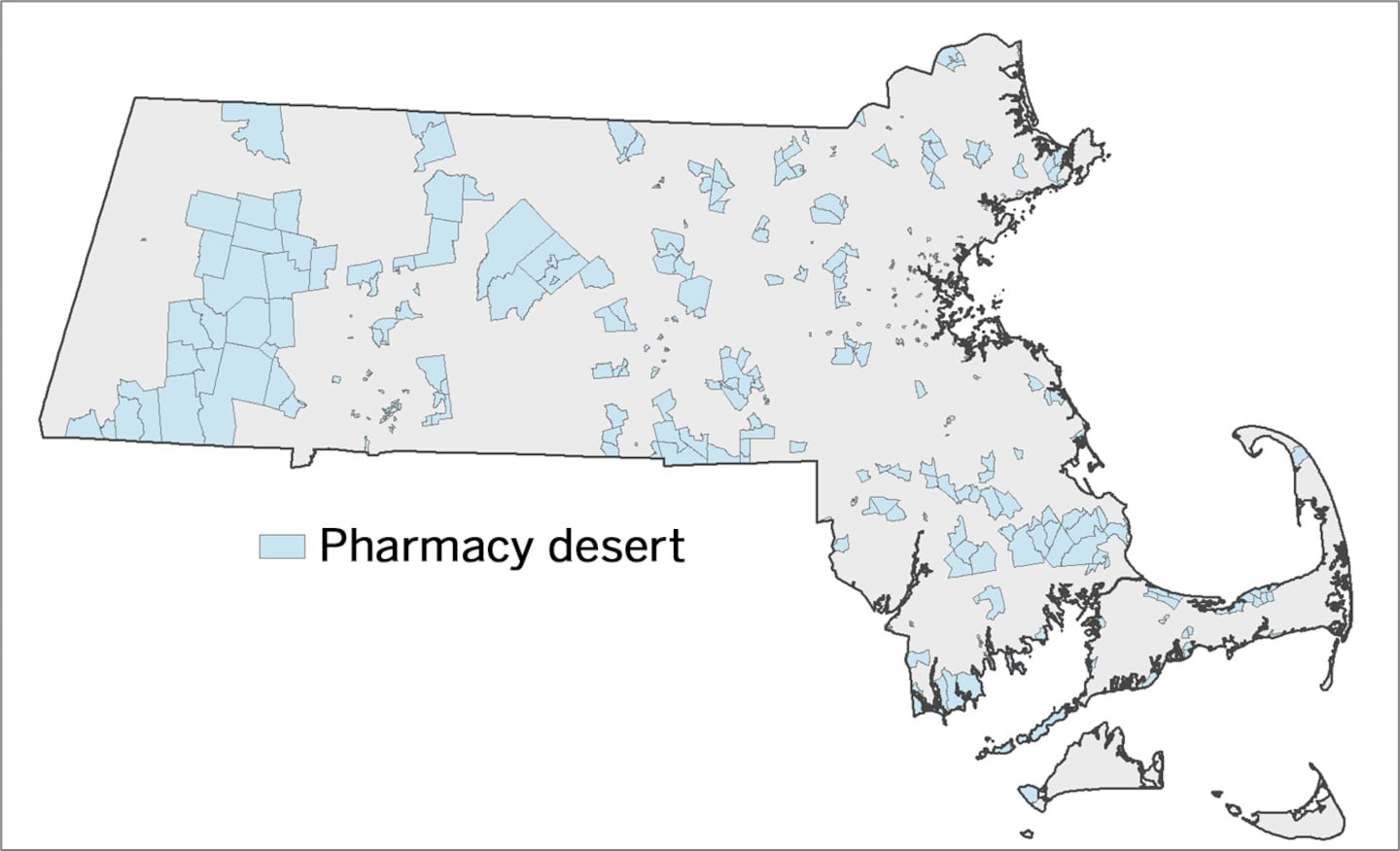

The largest proportion of Massachusetts pharmacy deserts (47 percent) are in urban areas, and deserts created since 2019 include neighborhoods in Boston, Springfield, Worcester, and New Bedford. Generally, urban pharmacy deserts are in areas where people have lower incomes. But pharmacy deserts are spread throughout the state, including in some rural parts of Western Massachusetts, the Health Policy Commission found. The commission defines a pharmacy desert as a census block that’s more than one mile from a pharmacy in an urban area, two miles in a suburban area, or five miles in a rural area, with an adjustment for areas with low vehicle ownership or low-income households.

This map by the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission shows pharmacy deserts in 2025 by census tract.Massachusetts Health Policy Commission

This map by the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission shows pharmacy deserts in 2025 by census tract.Massachusetts Health Policy Commission

One way to prevent closures is through payment reform to ensure that insurers compensate pharmacists — regardless of whether they are independent or part of a chain — a fair amount for dispensing drugs.

The Federal Trade Commission issued a report last year that documented ways in which pharmacy benefit managers (middlemen that negotiate drug prices and formularies with insurers, drugmakers, and pharmacies) negotiated higher prices for the same drug for pharmacies affiliated with the benefit managers than for unaffiliated pharmacies. The companies also use tactics like offering lower copays to steer customers to affiliated pharmacies.

Todd Brown, executive director of the Massachusetts Independent Pharmacists Association, estimated based on anecdotal reports from pharmacists that independent pharmacists lose money on about 70 percent of the drugs they dispense. “They’re left to try to eke out enough money to stay in business with the remaining amount of claims that are over the acquisition cost, but that’s becoming smaller and smaller, and PBMs are steering more claims to their own pharmacies,” Brown said.

Congress has been considering ways to regulate pharmacy benefit managers, including through an outright prohibition on the companies or insurers owning pharmacies. The Massachusetts Independent Pharmacists Association is pushing state legislation that would require insurers and pharmacy benefit managers to pay all pharmacies for drugs at a rate no lower than the rate paid by Medicaid. New York passed legislation prohibiting pharmacy benefit managers from penalizing consumers for not using pharmacies affiliated with the companies. Some states set rules around the rates that pharmacy benefit managers in Medicaid managed care programs can use to reimburse pharmacies.

But payment reform can’t be the only solution, since the decline in pharmacies is not unique to independent pharmacies. There have also been closures of chain pharmacies, retail-based pharmacies, and grocery-based pharmacies.

The Health Policy Commission research didn’t delve into the reasons for closures. Mike Tocco, president of Integrated Pharmacy Solutions, which provides pharmacy management services, said causes can include reimbursement challenges, a switch to mail order, the proliferation of shoplifting in inner cities, and the overwork of pharmacists in chain stores, which causes pharmacists to leave the field and fewer to enter.

Insurers could be part of the solution by expanding “preferred pharmacy” networks so consumers have more options to find a new pharmacy. Insurers could also cover medication for a larger number of days if a prescription is filled at a pharmacy that’s about to close, so that patients have more time to find an alternative. Community Health Centers could contribute by expanding pharmacy services in underserved communities.

One open question is whether there’s a systemic way for an insurer, pharmacist, or medical provider to reach out to customers who have filled prescriptions with a closing pharmacy to help them transition to a new pharmacy or method of ordering medication.

Legislation passed in 2024 established a state Office of Pharmaceutical Policy and Analysis. Its priorities should include figuring out how to support customers when pharmacies close — and how to shore up pharmacies so fewer close in the first place.

Editorials represent the views of the Boston Globe Editorial Board. Follow us @GlobeOpinion.