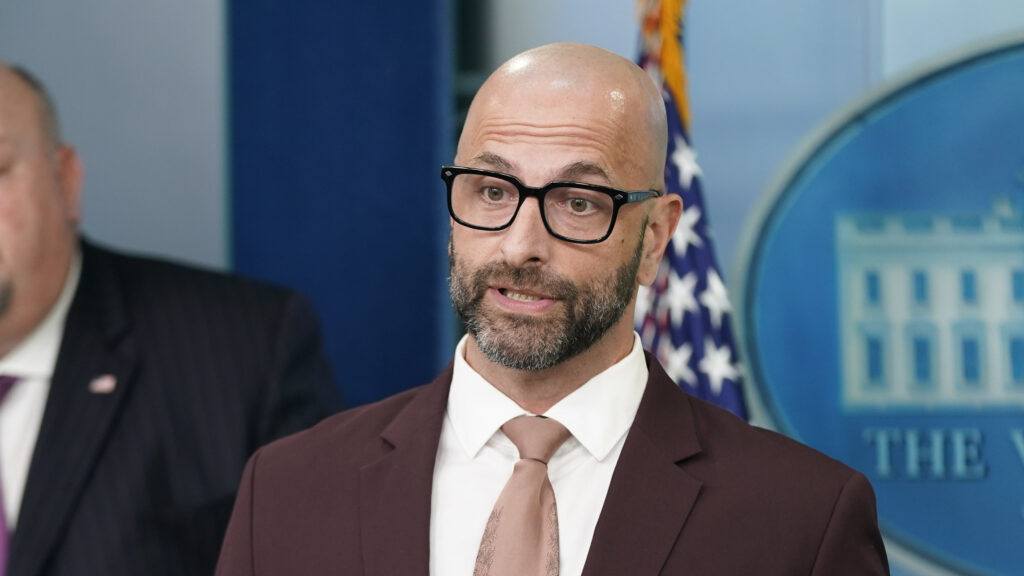

Demetre Daskalakis likens his former colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to “hostages.”

“They’re sitting there doing their work — they’re creating presentations, they’re analyzing data, they’re doing the surveillance,” said Daskalakis, a former top official at the CDC who resigned this summer along with two other leaders. “But then you have someone above who is making sweeping decisions without process and putting them on the CDC website as if they were gospel truth.”

That was a reference to the agency, at the direction of health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., recently reversing its stance that vaccines don’t cause autism, a move that Daskalakis said would have caused him to quit if he hadn’t already. He was with the agency for more than four years, beginning in the last days of the first Trump administration as the director of the Division of HIV Prevention. In 2022, he helped lead the White House’s mpox response. By the second Trump administration, he was serving as the director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

Despite Kennedy’s long record of anti-vaccine rhetoric, Daskalakis was initially optimistic about the potential for good public health policy. The feeling didn’t last. As Kennedy led mass layoffs and began making unilateral decisions — firing an entire vaccine advisory panel, handpicking the new members, changing Covid-19 shot recommendations — Daskalakis grew to believe science was being superseded by ideology. He began compiling a list of reasons that made it hard to stay in the job. The final straw wasn’t the shooting on CDC campus in early August, which sent bullets directly through his own unoccupied office windows. It was later that month, after the ousting of then-Director Susan Monarez.

“Enough is enough,” he wrote in his resignation letter, citing Kennedy’s undermining of the agency and vaccine policy.

Now Daskalakis, an infectious disease physician, is taking his skills back to the city where they were honed working in HIV clinics and as deputy commissioner of the New York City health department. Starting in February, he’ll serve as the chief medical officer of the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, the LGBTQ+ clinic announced Wednesday. He’ll also serve on the transition team for incoming New York Mayor Zohran Mamdani.

“As long as there’s a will to destroy public health, it’s going to be really hard to fix it,” Daskalakis said in an interview about his decision to move on from the CDC. “I feel more confident that my ability to help the community is best served closer to the ground.”

Daskalakis spoke to STAT about the importance of local health, how he decided to leave the federal government, and what he thinks about Kennedy’s latest moves.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You’re taking on the role of CMO at Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, and you’re also one of a couple dozen people on the health committee within Zohran Mamdani’s transition team. I’m struck by how locally focused both these positions are. What made you interested in these roles after leaving your position at the CDC?

My career has taken me from local to federal. I started really doing clinical work in New York City, and learned to do public health as an attending physician at Bellevue Hospital. Then I moved to the Department of Health in New York City and then over to CDC. As I learned more from the local, it became important for me to go to the place [CDC] where that local experience would influence the direction that public health went nationally and, frankly, globally.

In an environment where I really don’t think that federal public health is able to actually execute on its mission, this is when it’s time to go back to local. For me, the opportunity to go back to New York City and back to the grassroots front line is extremely appealing. It becomes a local charge to have to execute on the public health mission. And I believe in the work that Callen-Lorde does — LGBTQ work has been at the core of my career in so many different things that I do. And New York City — though I was born in D.C. — is where I grew up from the perspective of my own social awareness as well as public health. And so all of it made sense to go back to my roots.

Can you talk about what your work will look like in each of these roles?

We haven’t had our first health subcommittee meeting [for Mamdani], so I will know more when we go. … We’re going to give him the advice that he needs to be able to move forward with a very strong health agenda.

Chief medical officer at Callen-Lorde, that’s literally going back to my clinical roots, but also my community roots, so it sort of blends the two. I’ve always seen patients, no matter where I’ve been. When I was running parts of the [New York] Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, I was seeing patients at Mount Sinai. When I was working at CDC, I was seeing patients at Grady Hospital, at the Ponce clinic. So I will be seeing patients at Callen-Lorde, which is exciting. And then as the chief medical officer, I think my job is going to be making sure that the science and the operations are working together in a way that really provides the highest level of care and services to the LGBTQ+ population in New York City.

One of the things that’s great about not being at the federal government anymore, is that I’m able to comment on mis- and disinformation. Rather than misinformation, it’s really a lot of distortion. As a physician, as a clinician, and as someone who’s been a public health expert, I feel like my role is to continue to differentiate signal from noise. That’s part of what I’m going to be doing at Callen-Lorde for the community. It’s important for physicians to speak out, and medical providers to speak out, especially when they’re seeing things that are potentially bad for their patients.

Many children’s hospitals have stopped providing gender-affirming care to young people as the Trump administration threatens federal funding — even community health systems similar to Callen-Lorde, like Fenway Health in Boston. What’s the impact for young patients when that care is removed? And are you worried that Callen-Lorde may make a similar decision at some point?

At the base, medical decisions should really be between patients, their families, and medical providers, and should be based on science and free of partisan politics. New York is the right place to be to make sure that we can continue to deliver on that mission. And so that’s why I’m excited to go. Is it going to be simple? No, it’s going to be really complicated. But I’ve never shied away from complexity.

Where there’s risk — that’s a place that I really like to work. And so, do I think that the answer is going to be straightforward for Callen-Lorde? No. But what I do know is that they have a legacy of delivering on the mission to serve their community, and so I’m going to be a part of that legacy. I do have all of the appropriate concerns that I think everyone should have in health care right now, because the current regime over health in America is making bad decisions based on ideology. But I also have faith in the leaders of Callen-Lorde, faith in New York City, and then, frankly, the experience to be able to navigate some potentially turbulent waters.

You left the CDC in late August when Susan Monarez was ousted from her role as director. Can you walk me through how you made that decision? What factors were you weighing, and was there anything that gave you pause?

My doctor gene is really strong with this one. My main acid test … was if I felt that I was somehow going to do more harm than good. My oath to first do no harm is something that I took very seriously. And as I saw science being sidelined, and ideology not based in science becoming the communication strategy of CDC, I really couldn’t stay there and have my powers be used for evil instead of good, right? Being there as sort of a leader and allowing things like the autism website to go up — I would have quit then as well.

Now, my resignation letter was not something I wrote in 10 minutes. I’d been compiling a list of the things that were making it hard for me to stay. But each of the things that I listed before the last one were things that we were able to mitigate. When [Kennedy] announced that there was going to be a change to the Covid vaccine schedule for kids and pregnant women, we mitigated the harm of that by working to create the shared clinical decision-making. And frankly, [the administration] is sloppy. So seemingly, they said a [Covid] vaccine shouldn’t be given to a pregnant woman, but then they also said that pregnancy was a risk factor. So that allowed some wiggle where that wasn’t the end of the world. But when it was clear that they were just going to put up conspiracy theories, have presentations that had nothing to do with data that was at all reviewed, that was the end for me, because I couldn’t just sit there and watch.

I’m sure eventually I would have been fired. But I took the perspective … that my voice is really important in making sure that people know what’s happening. And so I elected to resign without a job, without a prospect for what was next, which really let me share what the inside was like.

Have there been any moments since leaving the agency that you regretted it, or where you felt like, if you were still there, you could have stopped something that wasn’t based on sound science from happening?

That’s why I left, because I found that there was no way to mitigate, because they were circumventing all of it. Let’s go over what happened with the website for autism and vaccines. The scientists were not involved with putting that up. They went around the scientists and they went to the web team and said post it. And so that would have been under my watch. And so rather than regret or going, “Oh, I could have helped fix it,” unfortunately, more than anything, I go into the “I told you so” zone. Because I do feel like as long as there’s a will to destroy public health, it’s going to be really hard to fix it. There’s this ongoing will to try to destabilize it.

I really feel badly for the folks who are still there and they’re heroes for hanging in, but I’m sure all of them are thinking, “where’s my line?” And I think that’s a decision that you have to make for yourself.