While extensive studies have found Covid-19 vaccines to be safe, effective, and to have saved millions of lives during the pandemic, these shots come with a rare but real risk of inflamed heart muscle, or myocarditis. Scientists on Wednesday reported that they have identified a pair of immune signals they believe drive these cases — and offered early evidence that these signals can be blocked.

Researchers sifted through previous Covid vaccine studies and identified a pair of immune signaling molecules, or cytokines, present at higher levels in the blood of vaccine recipients with myocarditis: CXCL10 and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). The authors found that these signals could also be triggered in the lab when immune cells were exposed to the Pfizer and Moderna Covid vaccines, or when mice were inoculated.

Scientists found that using antibodies to block CXCL10 and IFN-γ reduced signs of cardiac stress in vaccinated mice and in cardiac spheroids, three-dimensional growths of human cells meant to mimic some aspects of the heart’s structure and function. The authors also found they could block the cytokines’ effects with genistein, a compound found in soybeans and other legumes that has been linked to reduced inflammation.

The findings, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, come as messenger RNA vaccines face scrutiny from the Trump administration and some lawmakers. That has forced researchers studying these shots to strike a tricky balancing act between reporting new insights on adverse events while making clear that the shots are safe overall.

“I want to emphasize this is very, very rare. This study is purely to understand why. In those rare cases, what’s going on? People talk about it, and here we provide a mechanism,” said Joe Wu, director of Stanford Cardiovascular Institute and the study’s senior author.

Experts say top FDA official’s claim that Covid vaccines caused kids’ deaths requires more evidence

Kathyrn Edwards, a professor emerita at Vanderbilt University and a veteran vaccine researcher who was not involved in the new study, noted that the mouse findings come with caveats, as animals in the study received higher vaccine doses relative to their body size than vaccinated people. Wu acknowledged the point, adding that the research team used a higher vaccine dose to ensure that the animals would develop myocarditis. Otherwise, he estimates, it might have taken a whopping 20,000 mice to see the rare adverse event.

Billions of doses of mRNA vaccine have been administered worldwide against the SARS-CoV-2 virus, including in countries with large, centralized health systems, such as Canada, England, South Korea, and Israel. Data from those countries and the U.S. allowed researchers to spot cases of chest pain, shortness of breath, and palpitations in some recently vaccinated people. These symptoms, which were mostly mild, appear after about 7 out of every million first vaccine doses. The frequency rises to 31 cases out of every million second doses, and 60 out of every million doses among men under 30.

SARS-CoV-2 infection causes myocarditis at much higher rates than immunization, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting 1,500 cases per million Covid-19 patients. Cases caused by infection also tend to be more severe than those induced by immunization.

While researchers initially hypothesized that vaccine-induced myocarditis might be caused by an allergic response to the shots or autoimmunity, more recent research has pointed to inflammatory proteins. To better understand which of these signals are most important, a team led by Stanford scientists analyzed data from a pair of previous studies that collected blood from vaccinated individuals. Researchers found that CXCL10 and IFN-γ were more abundant in patients with myocarditis than in vaccinated people who didn’t develop the condition. They also saw that these cytokines ramped up within the first couple days after immunization — around the time myocarditis symptoms appear. Previous research has shown that levels of these cytokines drop a few weeks after vaccination.

Further experiments with lab-grown immune cells suggested that CXCL10 was mainly made by macrophages, cells that act as sentries in scouring for signs of infection and sounding the alarm. The CXCL10 they produce acts like breadcrumbs for immune cells, guiding them toward an infection site. IFN-γ, which plays a range of roles in beefing up antiviral defenses, was mainly made by T cells, which like generals shape the size and strategy of an immune response. When heart muscle cells were exposed to these cytokines in the lab, they struggled to contract rhythmically — suggesting that the immune messengers may impair the heart’s ability to supply the body with oxygenated blood.

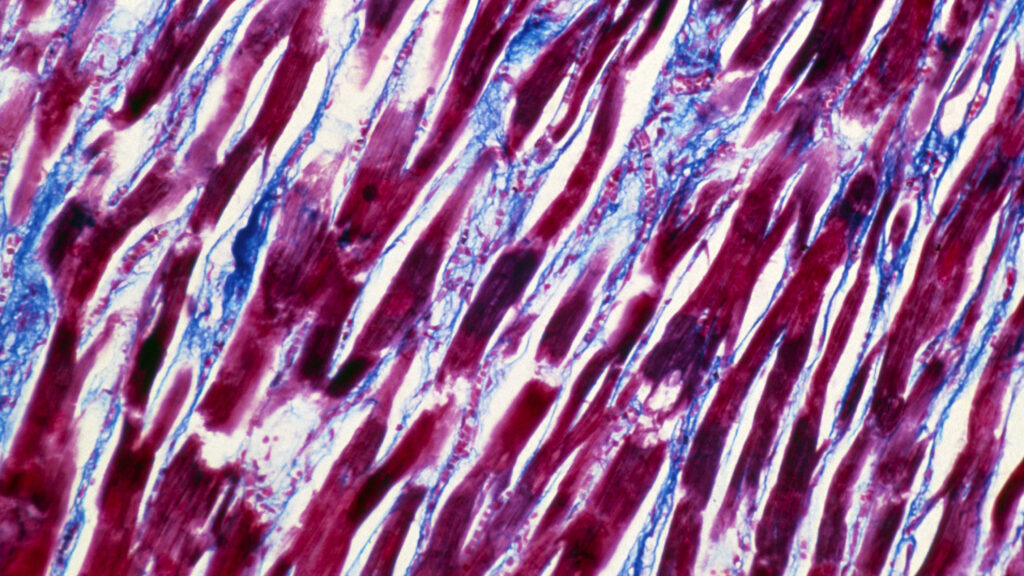

The authors then tested whether blocking these cytokines could prevent myocarditis. They gave mice two shots of Pfizer and BioNTech’s vaccine, with some of the animals also receiving antibodies that block CXCL10 and IFN-γ. Immunized animals given the antibodies had lower circulating levels of cardiac troponin, a protein that’s a telltale sign of heart damage when found in the blood. These mice also had fewer immune cells wending their way through heart tissue than animals only given the vaccine.

Researchers found that genistein had the same effect as using these blocking antibodies, blunting myocarditis in inoculated mice and in cells grown in the lab. The authors tested the molecule in part because they suspected sex hormones might help explain why males are more likely to experience myocarditis (genistein mimics the effects of estrogen).

Eric Topol, a cardiologist and geneticist who directs Scripps Research Translational Institute, said the study offers some of the best evidence yet to explain what triggers myocarditis in some vaccinated people. But he added that some questions linger.

“I was convinced by what they presented,” said Topol, who was not part of the study. “What I’m still left with is, why? Why does the mRNA lead to these cytokine disruptions?”

Wu’s group is now exploring whether genistein could one day be used to prevent or treat myocarditis. The compound is sold as a dietary supplement and found in foods such as tofu, but the preparation used in the recent study was more concentrated than what you’d find at the store. Wu and colleagues are looking to see if they can tweak genistein so that more of it ends up in the bloodstream.

This work comes at a fraught time for mRNA vaccines. Some state legislatures have looked to ban mRNA vaccines, and the Trump administration has cancelled $500 million in contracts for research into shots based on the technology. Earlier this year, a Senate subcommittee held a hearing on, as it put it, “The Corruption of Science and Federal Health Agencies: How Health Officials Downplayed and Hid Myocarditis and Other Adverse Events Associated with the COVID-19 Vaccines.” More recently, the Food and Drug Administration’s top vaccine regulator claimed Covid-19 vaccines caused the deaths of at least 10 children, though it’s unclear if those cases involved myocarditis and experts are skeptical of the agency’s assertion.

Edwards worries these moves aren’t backed by sound science and could undermine public health. But she noted that there is value in studies such as this latest paper that rigorously study vaccine side effects, even rare ones.

“We really shouldn’t throw the baby out with the bath water when the vaccines were highly effective,” she said. “If we could figure out why [myocarditis] happens, if we can mitigate it so that we could use the vaccine so that nobody gets it, that would be great as well.”