On-again, off-again plans to protect habitat used by about 5,000 pronghorn that migrate through the Red Desert and the Golden Triangle region east of Farson are once again off-again.

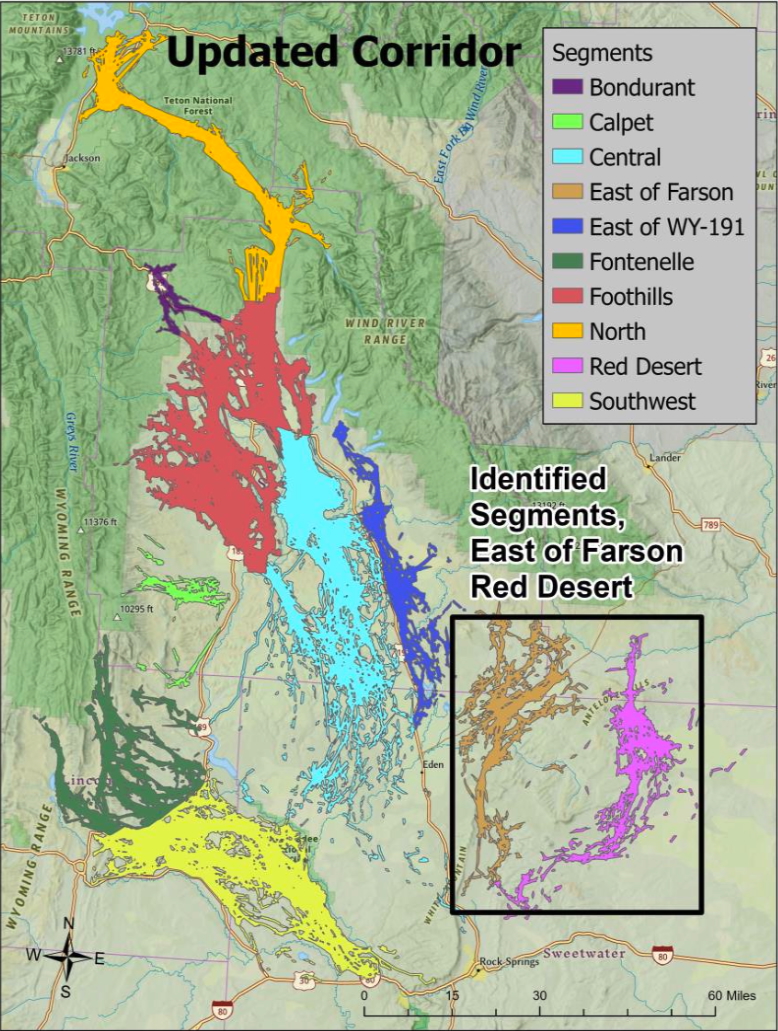

On Thursday, Gov. Mark Gordon announced that he was moving forward with the next step of the labyrinthine process for designating western Wyoming’s Sublette Pronghorn Migration Corridor, which began six years ago. But the governor explained that he sought to only protect eight of 10 segments that have been mapped, leaving out the two easternmost areas.

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department proposed the same plan in September, trimming off 270,000-plus acres, but that proved unpopular largely because it emanated from the livestock industry. Later that month, the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission reversed course, adding the two segments back.

Now Gordon, who’s appointed all the sitting Game and Fish commissioners, has trumped their proposal to designate the corridor in full. Under Wyoming’s migration policy, it’s ultimately the governor who decides whether a route gets designated.

This is the first test of the state’s migration policy, and it’s been a bumpy road that illustrates the difficulty of protecting energy-rich landscapes for wildlife’s sake.

Gordon was not available for an interview on Thursday afternoon.

Game and Fish Commissioner Ken Roberts discusses pronghorn during a September 2025 meeting in Lander. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

Game and Fish Commissioner Ken Roberts discusses pronghorn during a September 2025 meeting in Lander. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

Game and Fish Commissioner Ken Roberts said it was a “tough” issue, but that he respected the decision.

“I can’t take it personally,” Roberts told WyoFile. “We’re just part of the equation. I’m happy we got the eight [segments].”

Meanwhile, Wyoming Stock Growers Association Executive Vice President Jim Magagna, whose ranch is adjacent to the off-again segments, said that he was pleased. Although he first pushed the idea of trimming the pronghorn herd’s “East of Farson” and Red Desert segments, the plan was later adopted by the Game and Fish Department as its own. At the time, wildlife managers explained their support for leaving off the two segments because there were no “migration bottlenecks” there and threats to the habitat were relatively limited.

“I don’t buy that they did it just because I asked for it,” Magagna told WyoFile. “I think they did it because they did the review, and said that the science justified taking that approach.”

Notably, threats to habitat within the dropped segments may soon change. The Bureau of Land Management currently has a protective “area of critical environmental concern” in place overlapping much of the “East of Farson” segment, but the resource management plan there is being revised on a tight timeline. Concurrently, the oil and gas industry has shown significant interest in leasing ground in the area, including an especially ecologically valuable swath of the sagebrush-steppe biome known as the Golden Triangle.

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s plan to not designate two southeast segments of the Sublette Pronghorn Herd’s migration corridor, illustrated in this map, was denied by its commission at a September 2025 meeting in Lander. (WGFD)

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s plan to not designate two southeast segments of the Sublette Pronghorn Herd’s migration corridor, illustrated in this map, was denied by its commission at a September 2025 meeting in Lander. (WGFD)

Wildlife advocacy groups in Wyoming had mixed reactions to Gordon’s announcement. Craig Benjamin, who directs the Wyoming Wildlife Federation, said that he appreciated the governor’s decision to pursue the next step in the migration designation process.

“With pronghorn populations down roughly 40% and facing growing pressures on the landscape, it’s important that we work together to designate as much of the corridor as feasible to keep this migration intact,” Benjamin said in a text message.

The Wyoming Outdoor Council’s Meghan Riley struck a starkly different tone: “This decision subverts the will of the people and direction from the [Wyoming Game and Fish Commission] to the detriment of thousands of pronghorn in the Sublette Herd that will now be excluded from this process.”

“We are deeply disappointed with this decision,” she added, “but remain committed to seeing designation advance for the remaining segments of the migration corridor.”

Retired Game and Fish biologist Rich Guenzel was also disheartened by the news, calling it a “political decision” that ignores the herd’s biological needs.

“I would respectfully disagree with the governor on his assessment,” said Guenzel, who personally endowed a pronghorn-specific conservation fund. “I don’t know his rationale, other than they’re not biological.”

Efforts to protect the remaining eight segments of the Sublette Pronghorn Herd’s migration paths still face some hurdles.

Gordon will soon appoint a “local working group” consisting of two representatives of the agriculture industry, two “industrial users” (oil, gas, mining and renewable), two representatives for wildlife, conservation and hunting and a single rep for motorized recreation. Applications to the group are being accepted through Dec. 31.

“The local working group is ultimately charged with reviewing the Game and Fish’s risk assessment, corridor components, potential impacts to socio-economic conditions of the region, conservation opportunities, highway projects, and other factors appropriate to the potential designation,” a press release from Gordon stated.

Doug Brimeyer, left, converses with Hall Sawyer during a 1998 pronghorn capture operation in Grand Teton National Park. The migratory animals are part of the broader Sublette Herd. (Mark Gocke/Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

Doug Brimeyer, left, converses with Hall Sawyer during a 1998 pronghorn capture operation in Grand Teton National Park. The migratory animals are part of the broader Sublette Herd. (Mark Gocke/Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

After the working group’s deliberations, the decision will swing back to Gordon. If he designates the corridor, it’d be the first since Wyoming’s migration policy was revamped in 2019, but he can also kick it back to Game and Fish for refinement or reject it.

On the federal level, there have been efforts to protect the Sublette Pronghorn Herd’s migration paths for a quarter century. In 2008, the Bridger-Teton National Forest amended its forest plan, protecting that portion, and the route earned publicity and was given the moniker “the Path of the Pronghorn.” But its southernmost stretches, which cut through mostly Bureau of Land Management property, ran into political pressure and have remained unprotected ever since.