PART 1: Where Did My Peace and Quiet Go?

As I walk outside of my house and sit on the back porch, I settle in to listen to the peaceful sounds of local wildlife in the early dusk. But instead, I hear the roaring of an 18-wheeler or modified muffler coming down Highway 167.

As towns grow, they can grow louder. Brighter. Harsher. Due to a series of developments that can create a negative cumulative effect.

This series explores two intrusions that can diminish a community’s shared quality of life: light and noise pollution.

Noise pollution is unwanted or harmful sound that interferes with normal activities like sleeping, relaxing, working or even thinking. It can come from sudden bursts, like a slammed trailer gate on pavement from a yard cleaning crew getting started at 7am, or persistent sources like traffic, trains, or a dog barking constantly that somehow only the owner is deaf to…

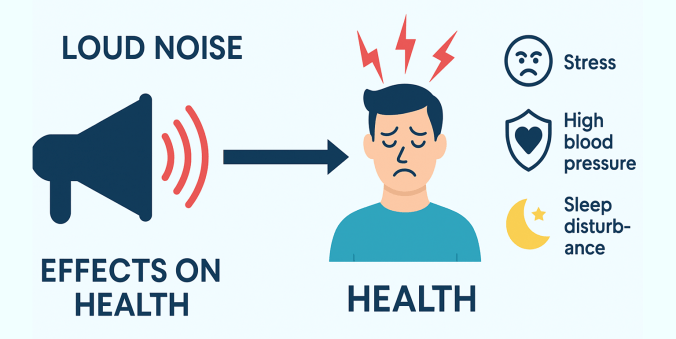

Our bodies respond to disruptive and excessive noise as a form of stress, even when we’re not consciously aware of it. Multiple research resources, from the College of London to Boston University, have shown that prolonged exposure to loud noises can increase cortisol levels, raise blood pressure and disturb sleep, all which contribute to a lower quality of life.

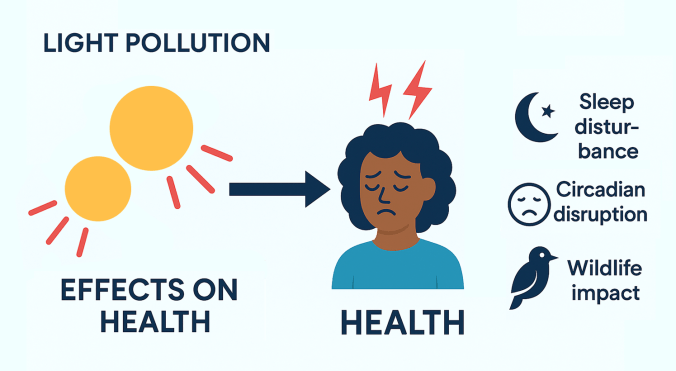

Light pollution on the other hand is excessive, misdirected, or artificial light that disrupts natural darkness. It includes everything from constant parking lots lighting, high-intensity street lights that spill into homes, skyglow that erases the stars, or LED signs that burn through the night.

Light pollution interferes with our sleep by suppressing our natural melatonin production and disrupting our circadian rhythm, and negatively affects wildlife by confusing animals that rely on daylight patterns to tell them when to eat, sleep and migrate.

Let’s take a closer look at these two nuisances, and the ways they affect our community, starting with sound pollution.

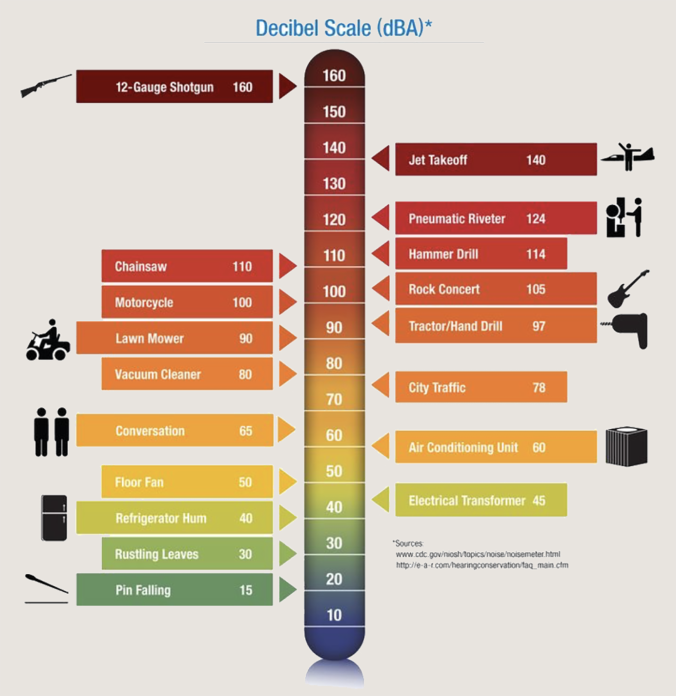

Reference dBA Scale.

Reference dBA Scale.

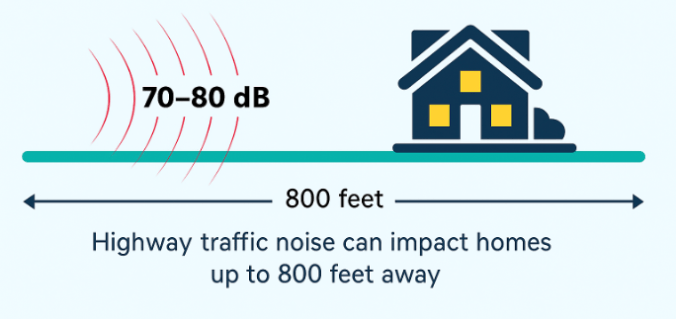

According to the World Health Organization, the 90-plus decibel volume of traffic that can be heard at any time of the day in our backyard falls well within sound pollution parameters. The constant hum and rumble of traffic is unavoidable, and we live over three and a half football fields off the highway with a good number of mature trees in our neighborhood. But the land is flat.

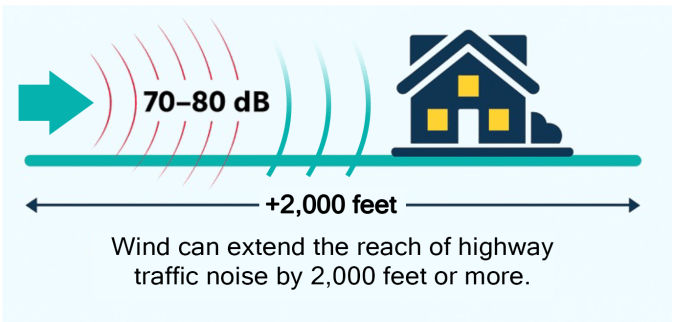

Noise travels horizontally outward from its source. Think of a traffic lane as the mouth of a megaphone, radiating out horizontally in all directions. Over flat land, especially with hard surfaces like pavement or bare ground, there is little natural absorption. Noise stays low and travels farther, rather than dissipating.

Over flat ground with few sound barriers, sound travels closer to 1,000 ft.

And if there is a strong wind? It carries sound waves even further as sound waves are pushed along the ground. In highly variable or gusty conditions, sound is scattered in multiple directions, causing sound to fluctuate, briefly getting louder or quieter as it spreads.

Without significant elevation changes or natural barriers to block noise, diverting it is a big challenge. According to the Federal Highway Administration, achieving a 50% reduction in noise requires a combination of elevated earth berms, dense evergreen buffers, and sound-dampening surfaces, none of which currently exist in Ruston at scale.

Let’s consider this impact alone to our area.

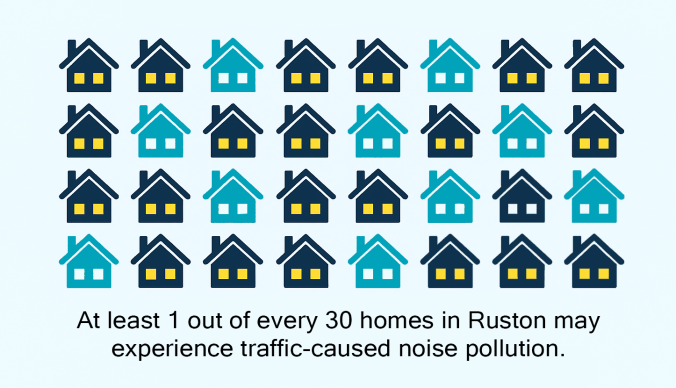

Local census data says we have about 8,500 homes in our community. Of those homes, 30% of them are as close as our house is to a major noise source like Hwy 167. That is over 2,500 homes that have negatively impacted quality of life due to a lack of effective sound pollution prevention.

And unlike water or trash, noise isn’t routinely measured or planned for by city governments. Without putting intentional strategies in place, the loudest parts of a town typically only get louder.

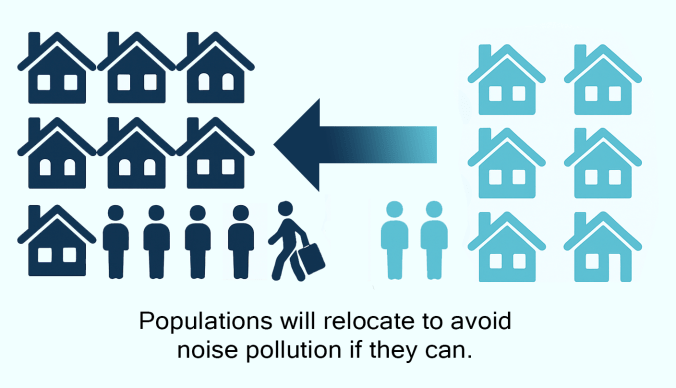

As intrusive noise levels rise, residents with the resources to relocate often move farther out of town, eroding the local tax base and shifting neighborhood dynamics. This leads to more transitional renters who, though not inherently disengaged, tend to have fewer reasons or opportunities to invest long-term in the area.

In the next installation of this article, we will take a closer look at light pollution and how it affects our community as well.