Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

When Robert F. Kennedy Jr. convened a panel on Monday to discuss “chronic Lyme,” many leading researchers of the disease were genuinely excited. Kennedy’s Department of Health and Human Services promised to allocate more resources to understanding the disease. There was hope, among experts, that this would mean an important new chapter for Lyme research.

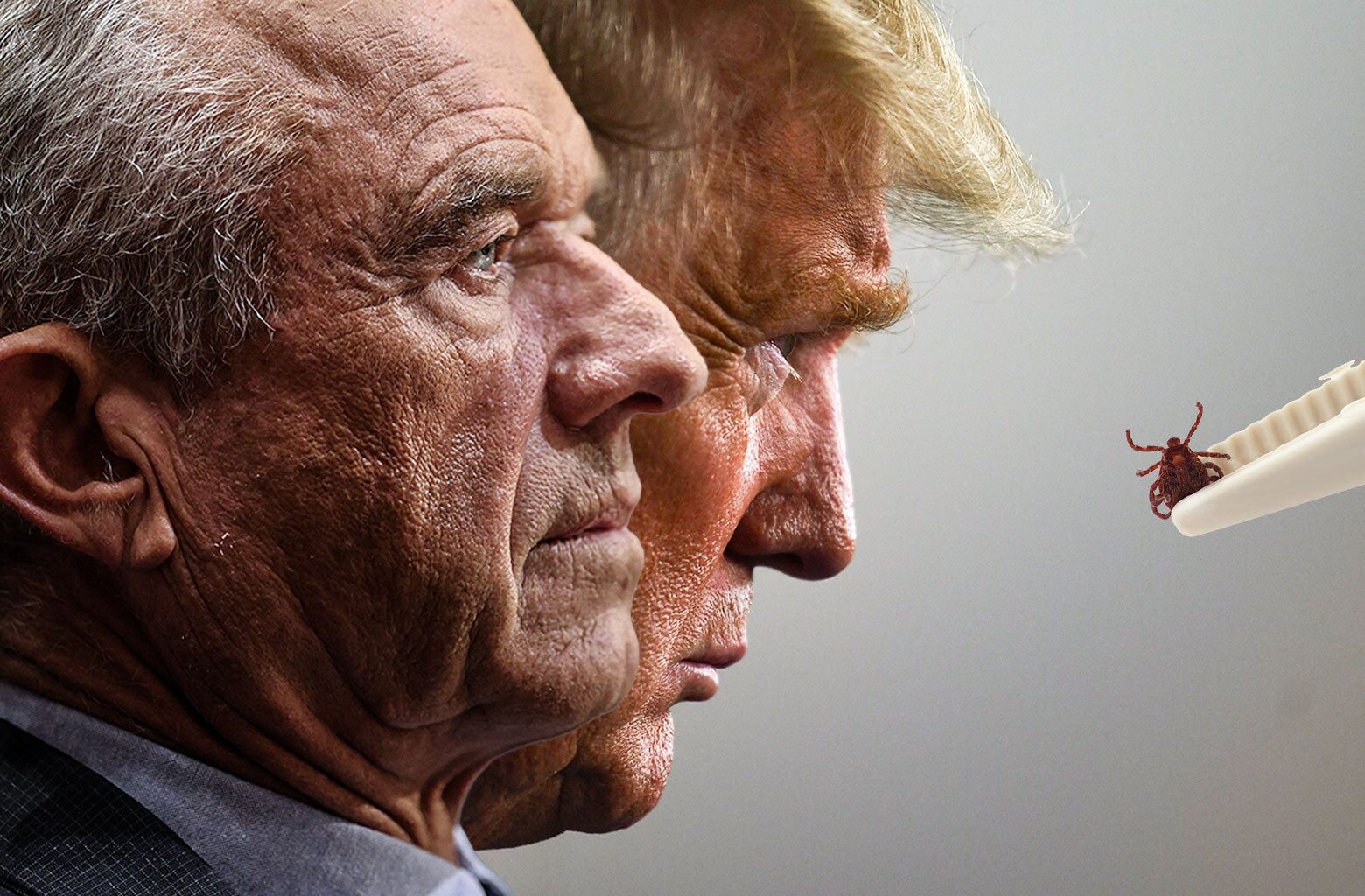

But there’s a problem: Kennedy is a conspiracy theorist with seemingly little understanding of how modern science works. It didn’t emerge in Monday’s roundtable, but Kennedy, for example, once claimed Lyme disease was developed by the U.S. military as a bioweapon in the ’70s. He still maintains that the medical community has “gaslit” the public over Lyme and even asserted, without evidence, that during the Biden years, there were top officials within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services who, due to political motivations, were “saying Lyme disease did not exist.”

This is not an ideal mindset to bring to any medical topic, but it’s particularly troubling for Lyme, given that it is already one of the most controversial diseases.

Active Lyme disease, identified in the 1970s, is not a particularly mysterious illness. The tick bite that transfers the bacteria typically causes an easily identifiable bullseye rash; once spotted, symptoms, which can include fever, headaches, stiffness, and fatigue, can be resolved with a round of antibiotics. The treatment of active Lyme is fairly straightforward. But the aftermath of active Lyme remains a deeply unsettled area of science. A subset of Lyme patients go on to complain of arthritis-like joint pain, fatigue, and neurological issues for years afterward. For a smaller population, the symptoms become debilitating. Some patients grow desperate and even suicidal.

Until recently, many mainstream medical professionals disputed the idea of “chronic Lyme” altogether, insisting that Lyme was done once it was treated with antibiotics. Any complaints the patients had afterward, they argued, likely resulted from other conditions or from psychiatric disorders, which can indeed cause severe physical symptoms. But patients don’t like being told something is all in their head, particularly when their lives are falling apart over a maddeningly persistent illness. As a result, a “Lyme community” began to form of patients who felt forced to become their own champions and validate one another’s suffering. Many looked for answers outside conventional medicine.

The rush of pseudoscientists, grifters, wellness influencers, and celebrity advocates into the space only made the chronic Lyme debate more fraught. Even the term “chronic Lyme” was, and is, highly charged: In medical literature, doctors call it Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome, in part to clarify that they are not referring to a continuous, chronic infection with the bacteria but only to a constellation of symptoms that develop and linger after confirmed bouts of Lyme disease. The people this term doesn’t include are those—often self-diagnosed laypeople or the patients of anti-scientific practitioners—who believe that they have insidious Lyme infections missed by blood tests and persistent beyond any normal antibiotic treatment. (The research does not show any evidence for a chronic Lyme infection, experts said.) These patients never developed the rash or had any other concrete evidence of Lyme infection. These are the cases that caused many in the mainstream medical community to dismiss “chronic Lyme” as nonsense.

But mainstream scientists weren’t entirely ignoring the possibility of both undetectable and chronic Lyme, as much as Kennedy may insist otherwise. Many researchers agreed there was a need for better testing and that it was possible that real Lyme sufferers were going undiagnosed. And even in the earliest Lyme studies, experts said, the National Institutes of Health had attempted to suss out longer-term damage. The problem, said Dr. Brian Fallon, the director of the Lyme and Tick-Borne Diseases Research Center at Columbia University, was that most Lyme research dealt primarily with “well-defined” patients—those with telltale rashes and active infection that showed on blood tests—in order to have clean, careful studies. Those patients were those with the easiest cases, with easy diagnostics and prompt treatment. The potentially messier cases, without rashes, or with long periods of infection without treatment, were not taken into account. The pace of the research moved relatively slowly, given that Lyme was never such an urgent problem. It is not deadly or contagious like Ebola or AIDS. For many patients, it’s more like a temporary inconvenience.

But two things changed. First, climate change has made Lyme an increasingly visible and pressing issue. As the tick population explodes across North America, Lyme has become a virtually inescapable threat in the Northeast and parts of the Midwest. Second, a global pandemic struck. In its aftermath, research institutions turned their resources to questions about COVID’s long-term effects. As they did, they began to bring those same questions to other infectious diseases that might result in chronic conditions.

“It shouldn’t come as any surprise to the world right now that infections can cause chronic problems, because of what we have learned from long COVID,” Fallon said. “I think it’s helped tremendously in changing the conversation. … There’s a great deal of interest in looking at something that’s been ignored.”

It is now a potent moment for Lyme research. If scientists can get the funding and resources they need to develop better diagnostics and unlock the mechanism that explains what is making chronic Lyme patients sick, it could bring profound relief to hundreds of thousands of Americans, allowing them to get the care they need. But a large part of pursuing a major medical breakthrough is separating science from pseudoscience in order to allow the scientific process to proceed with its dispassionate methods. And Kennedy has shown that he is incapable of that—and is steering his HHS accordingly.

There are urgent reasons, beyond the success of future research, for the leading medical institutions in the country to try to purge the lingering anti-scientific elements in the Lyme conversation: They may actually put patients’ health at risk. When confusion meets desperation, as it does when the Centers for Disease Control and the National Institutes of Health cannot provide any clarity, patients and doctors may seek out unconventional answers.

“A lot of these patients undergo bizarre, unapproved therapies, like extended intravenous antibiotic therapies, for months or even years,” Dr. Durland Fish, the chief executive officer of the American Lyme Disease Foundation, told Slate. “A lot of them are bogus.”

These treatments, Fish said, can be expensive, as they usually aren’t covered by insurance. And they can be deeply dispiriting when they don’t work. Some patients, he said, can become depressed and even suicidal.

And perhaps even more worryingly, if a patient becomes convinced they have chronic Lyme based on an influencer’s videos, they may be diverted from identifying something else. Part of the reason chronic Lyme has always been controversial is that its symptoms are so nonspecific. Fatigue, brain fog, headaches, and joint pain can be caused by anemia, sleep disorders, mental illnesses, arthritis, multiple sclerosis, lupus, ALS, fibromyalgia, cancer, and many other conditions.

“From my perspective, I think the misdiagnosis and mistreatment is a bigger problem than the actual Lyme disease,” he said.

Now, as chronic Lyme emerges from its era of hazy theories and pseudoscience, it continues to be tainted with its previous associations. As an example, New Jersey Rep. Chris Smith, who attended Monday’s hearing, slipped a provision in the National Defense Authorization Act, which passed Wednesday, requiring the Government Accountability Office to investigate whether Lyme disease was bioengineered by the U.S. military. (Lyme disease, it should be noted, predates the United States itself by millennia.) During Monday’s hearing, he complained that mainstream news media, including the Washington Post, had portrayed him and his allies “like we have a tinfoil hat on our heads.” Smith is a Republican, but conspiratorial thinking on Lyme is a bipartisan problem.

And few are as damaging to chronic Lyme’s reputation among skeptics as Kennedy himself. As head of HHS, Kennedy has baselessly attributed deaths to the COVID vaccine, connected both Tylenol and circumcision to autism, and linked SSRIs to mass shootings. In one throwaway comment in the hearing, he claimed that the antiretroviral drug developed during the AIDS epidemic under Anthony Fauci’s NIH killed more people than AIDS itself.

The panel he convened was similarly questionable. Participants were largely not the leading experts in Lyme research but instead patients, medical technology business owners, politicians, and people with out-there theories about the disease. One person claimed there was a connection between Lyme disease and autism—something no mainstream researcher seems to find credible. Another person, who is a patient and an HHS official, asserted that had she followed standard medical Lyme treatments, “I would be dead today.” Lyme disease is not a fatal disease.

Still, Fish, like the other experts, said that Kennedy’s NIH putting more resources into understanding chronic Lyme could be extremely helpful for the thousands of Americans struggling with mysterious symptoms. These patients, he said, need answers and better diagnostic tools.

“These patients have serious illnesses, and I don’t blame them for raising hell about the situation,” he said.

Lyme is a disease that makes sense as a target for Kennedy, as obsessing over chronic illnesses is a core tenet of the “Make America Healthy Again” movement. Kennedy has said one of his sons developed Bell’s palsy from Lyme and that one son developed severe, debilitating chronic Lyme. Kennedy is also, fittingly for his family’s reputation for being full of robust outdoorsmen, a big proponent of getting outside into the woods—advice being made dangerous by the ticks. He noted the “spiritual” value of the outdoors in his address Monday.

Lyme also makes some sense as a target for the moment, when there is no epidemiological crisis such as SARS or COVID or AIDS consuming all the oxygen in the conversation. Leading experts in Lyme say people are beginning to understand the “insidious epidemic” of Lyme, as Dr. John Aucott, the director of the Johns Hopkins Lyme Disease Clinical Research Center, put it. He and Fallon expressed the need not just for studies and testing but an entire built-out academic infrastructure around it. Right now, most academic programs are struggling under federal budget cuts; Lyme research is one area where Kennedy’s personal interest may be of use.

Marianne Lavelle

The Real Reason Trump Is Dismantling the Research Center That Helps Keeps You Safe From Extreme Weather

Read More

For countless Americans, this could be great news. Aucott noted that he watched AIDS go from a death sentence to a manageable condition—proof that painstaking, rigorous research can revolutionize the understanding and treatment of a new disease. Today, he said, some of his Lyme patients are sicker than the AIDS patients were at the end of his time treating them.

This Content is Available for Slate Plus members only

The Kash Patel Girlfriend Controversy Couldn’t Get Any Dumber, Except It Just Did

This Newspaper Editorial Should Be Making Pentagon Leaders Sweat

Hopefully, Kennedy’s anti-science approach will not impede the evidence-based Lyme research that comes. His sloppiness, as when he repeatedly during panel discussions conflated Lyme disease and Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome, may not carry through to actual policy. And in at least one way, experts gave Kennedy credit on something else: He’s right, they said, that most people are not just sick from psychosomatic causes. “These are complex illnesses we’re just starting to understand,” Aucott said. “They’ve got a hard-to-explain illness. That doesn’t mean it’s just in their heads.”

But when diseases are particularly complex, and when the medical understanding of a topic shifts rapidly, it’s particularly damaging to have a man who consistently undermines the mainstream scientific community as the face of its public health response. The public needs clarity from its government, not just disruption. In this case, clarity doesn’t just mean validating suffering patients’ frustrations. It means acknowledging the limits of our knowledge while having an open mind—and focusing not on heated feelings but on the scientific process.

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.