To call the Immaculate Reception “immortal” would be to call the view from Mt. Washington “pretty.”

In terms of Pittsburgh permanency, the Duquesne and Mon have nothing on the fateful play that took place on Dec. 23, 1972.

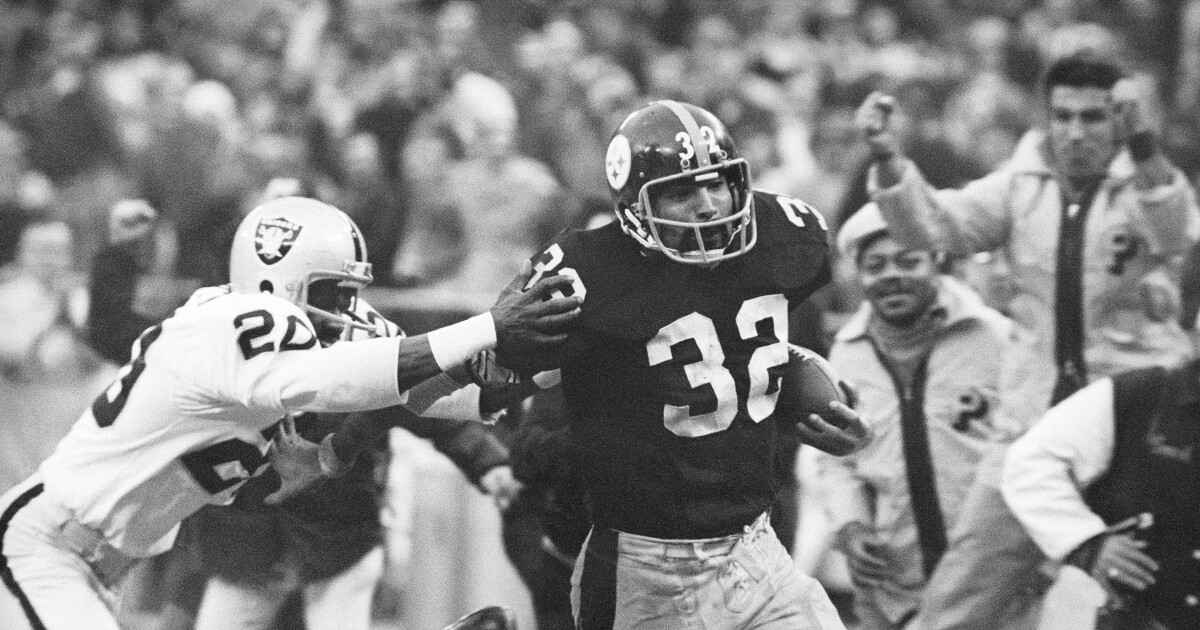

With seconds left in the 1972 AFC Divisional Playoff against the Raiders, Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw threw a desperate pass that was deflected into the air. Running back Franco Harris famously caught it just before it hit the ground and ran it in for the game-winning score.

Its story got its own NFL Films presentation. The Harris statue at Pittsburgh International Airport and Heinz History Center depicts the Steelers running back gathering the ball off the Three Rivers Stadium artificial turf enroute to glory.

As recently as 2019, a panel of 80 football aficionados voted the play the greatest of all-time on NFL Network.

But before all the national acclaim, myriad recounts, and before it was even dubbed “The Immaculate Reception,” the first person ever to tell the story was just a kid from East Liberty.

Friendship with Franco

“I used to go to Vento’s Pizza after class at Peabody High School,” said Mike Silverstein, whose stomping grounds were just off Stanton Ave.

Vento’s is Pittsburgh-famous for its Sicilian slices oozing with inch-thick provolone cheese.

Vento’s is world-famous for being the homebase of “Franco’s Italian Army,” the fan club of Harris, started in 1972 by Al Vento and business partner Tony Stagno.

One may assume a man with his own army would commute to work in his own armored vehicle.

Sherman tank? Surely not.

“He would take the 71 Negley bus unless somebody drove him,” Silverstein said.

”Franco had a friend from Penn State whose brother was a fraternity brother of mine.

“So I said, ‘Hey, do you know Howie’s brother?’ And he said ‘Yeah, sure,’ and we talked in the locker room, and I heard that Franco was taking the 71 bus to work.

“And I lived at the time in the East End and I heard that he lived in Friendship and I said, ‘Hey, you want a ride to work?’ And he said, ‘When do you go?’

“It turned out on Tuesdays I went to work the same time he did, because that was when they had film study. So I went and picked him up a couple times and we drove into work.”

That arrangement came to an end, Silverstein said, after the Steelers public relations department set up a series of public appearances for Harris at a local Chrysler-Plymouth dealership or two, which resulted in the then-rookie’s use of a car.

But somewhere in those 15-minute commutes between Harris’ apartment on Harriet St. and the Steelers’ team facility at Three Rivers Stadium, seeds of a casual friendship were planted that would sprout into opportunity for young upstart journalist Silverstein on an unseasonably humid December day later that year.

Stringing along

“I was a 24-year-old kid trying to survive in radio, trying basically to find some way to get a career out of this thing,” Silverstein said.

Silverstein had been working as a freelance journalist in the nation’s capital when a station he’d been covering was Pittsburgh’s NBC-owned WJAS. NBC in 1972 was in the process of selling WJAS to Heftel Broadcasting, which planned to flip the station’s format from news-talk to top 40.

“So people were quitting left and right and I figured, ‘Hey, I can get a job there even if it’s for a couple months — it’ll look great on my resume that I work for NBC.’

“So I get a job there knowing I’m going to be fired in a couple of months when the sale goes through. Radio is a crazy business.”

The station stayed true to its news-talk identity until the format flip in March ‘73, and the powers-that-were-soon-not-to-be allowed Silverstein to work a side hustle as a stringer for ABC Radio, namely a weekend sports program called “World of Sport.”

“ This was before ESPN. And you would go around at six minutes past the hour to the various baseball or football games, and they would talk to [stringers] at the games, and they’d give you an update on what was going on with the Browns versus the Bengals or the Bears versus the Packers, or whatever,” Silverstein explained.

“And whoever was the stringer there would get $25 to do a 25-second on-scene report.”

Silverstein became a mainstay of the Three Rivers Stadium press box during the 1972 regular season, covering every home game, from the Steelers 27-7 season-opening shellacking of the Oakland Raiders to the week 12 shutout of the rival Cleveland Browns, 30-0.

The Black and Gold finished the season 11-3, good enough to qualify for their first postseason appearance since 1947, and only their second playoff participation in franchise history.

Prior to 1975, the NFL determined which teams would host playoff games based on a rotation of divisional winners. 1972 happened to be a year that the winner of the AFC Central division would get a home game, which meant the Steelers would be playing at the Confluence for their divisional round game against the Raiders, who won the AFC West division.

But while the local football team wasn’t going to be displaced, the same could not be said for the local media outlets covering said team.

As national attention descended upon the Steel City, television crews were placed in the preferred vantage points so that cameras could have a symmetrical, panoramic view of the field.

“Networks were in the football press box, which was on the 50-yard line,” recalled Silverstein.

“I was put in the baseball press box because I was a radio guy.”

And so it was from the space usually reserved for Pirates games that Silverstein would be filing his live football reports to the national ABC studio in New York.

With the game set to kick off at 1 p.m., Silverstein would be responsible for a pregame report at 12:06, and live game reports at 1:06, 2:06, and 3:06.

“And then here comes the really difficult one – 4:06. Because the game’s gonna be over and I have to go get tape in the locker room and yet still have to be available for 4:06.”

The launch of a dynasty and a career

It was appropriate that the game took place over a half-year before the Fourth of July because, for the first 59 minutes, there was an absence of fireworks.

No points were scored until the Steelers finally broke the ice with a field goal in the third quarter.

With 1:13 left to play in the fourth quarter, Raiders QB Ken Stabler ran 30 yards to the end zone, giving the Steelers the ball back, down by a 7-6 score.

Following the ensuing kickoff, the Steelers managed to get the ball to their own 40-yard line.

Futility on two straight plays meant a third down-and-10, with 26 seconds left on the clock.

“It’s about 3:30 in the afternoon. And I’m like, ‘I’ve gotta get some tape and be back to do a live shot at 4:06,’” Silverstein said.

“How can I be – like Firesign Theater said — in two places at once when you’re not anywhere at all? So at 3:30, it’s third-and-10, and the pass falls incomplete, and I go run to the elevator.

“I’m gonna miss the fourth down play. The elevator opens.

“There’s Phil, the elevator operator, there’s a group of people on the elevator including [Steelers owner Art] Rooney, but the elevator is pointing up. And so I go back to the baseball press box, which is 10 seconds away… and watched the Immaculate Reception.”

The race was then on, Silverstein said, to gather the sound he needed for his 4:06 deadline.

“I went immediately to the elevator, which was now coming back down from the fifth level. Mr. Rooney was on the elevator and had this quizzical look on his face.

“ I realized that he’d been on the elevator when [the Immaculate Reception] happened because I saw him going up and then I caught him going back down. And I told him that Terry [Bradshaw] was flushed out of the pocket and scrambled.

“The one thing I remember that I said was he threw the ball to [Steelers fullback] Frenchie [Fuqua] and it ricocheted — I remember using the word ‘ricochet’– and Franco caught it and ran it in for a touchdown.

“I don’t remember exactly what he was wearing, but I do remember he had an unlit cigar in his mouth. And he kinda looked at me with this puzzled look, and he just said, ‘Well, I’ll be. Hah baht that?’ in the perfect Yinzer accent.”

By the time the elevator hit field level, Silverstein figured the game was over and expected to see players walking through the tunnel to the locker room. When that did not materialize, and with the minutes ticking towards his 4:06 live radio hit, Silverstein improvised.

“I had a field pass around my neck, but that was only good before the game. There is no such thing as a field pass after the game, but I showed it to a guy there and I walked onto the field — not the playing surface, but the sideline, down the end line beyond the end zone, and then over onto the Steelers side of the field, and there was this 15-minute argument [about whether or not the play should stand as a touchdown], which was why nobody came off the field.

“The game wasn’t over.”

With five seconds still left on the game clock just moments after a play whose legend would launch a professional sports dynasty, those car rides from Friendship to the North Shore and back culminated in a moment that would launch Silverstein’s career.

“I see Franco and I’m holding my Sony tape recorder in my left hand, and I raised my right hand. ‘Frank, Frank, Frank.’

“And he looks over and he comes over and I said, ‘can we do a quick interview?’ And he says ‘sure.’”

Silverstein: Franco, was it the luckiest play you ever had?

Harris: Yeah, I think it is. I was damn lucky.

Silverstein: Were you supposed to be out there on that play or did you just go out there to be so open?

Harris: No, I wasn’t supposed to be out there at all.

Silverstein: What happened?

Harris: I just went on out there. I thought Terry was being trapped. I went out there and maybe he’d throw it to me. But he threw it out there, it bounced up, and right place at the right time.

Mike Silverstein and Franco Harris, moments after the Immaculate Reception

A big cheer can be heard at the end of the interview. That was the moment the referee, Fred Swearingen, confirmed the play as a touchdown.

“At that point, I said ‘I better get outta Dodge. The game is on and I have no business being down here.

“God knows what they’ll do to me because I shouldn’t be on the field.”

After one last-second pass by the Raiders that fell incomplete, handing Pittsburgh the win, Silverstein made a mad dash back to the elevator and up to the press box.

When he got there, which he estimated was at 3:47 p.m., he immediately phoned ABC, where producer John Chanin was standing by, awaiting Silverstein’s phone call for the 4:06 broadcast.

“I said ‘I’ve got an interview with Franco Harris.’

“He turned to Lou Boda, who was the anchor, and said, holy [expletive] Lou, Mike’s got Franco Harris.’

”And they used the tape. They actually had it on the 4:00 network news as the lead.”

Parlaying a moment into a life’s work

Having helped ABC beat other national outlets with the story of Harris’ catch, complete with the interview, Chanin invited Silverstein to meet with him and other higher-ups at the ABC corporate offices.

Silverstein was hired by ABC as a news writer, later sliding into the editor’s desk and running ABC’s Washington, D.C. bureau, retiring after 31 years.

But in reflecting upon all professional successes, such as his seven Writers Guild of America awards and the Columbia-duPont Award he and his D.C. team would win for overall coverage of the September 11 events as well as for the corresponding TV special, “Answering Children’s Questions,” Silverstein attributes it all to the Immaculate Reception.

Much like the man who made the play said about his own luck, Silverstein believes he, too, was in the right place at the right time.

“We didn’t know at the time, but [then-Steelers’ director of communications] Joe Gordon did me this incredible favor, to put me in the baseball press box, which was not on the 50-yard line, but it was right next to the elevator to take you down to the basement, the playing field, the locker rooms and all that.

“And that turned out to be one of the best things that ever happened in my life.”

Epilogue

“To a large extent, I owe my career to this man,” Silverstein said of Harris. ”Walking away from his teammates and coming up and doing an interview with me was the springboard to all of these things.

“He used his platform to make everyone feel better.”

That statement came to life during an event at Heinz History Center surrounding the 40th anniversary celebration of the Immaculate Reception.

”I had my press pass for the locker room [from the day of the Immaculate Reception], and I wanted to do something positive. So I took the press pass to the event,” Silverstein said.

“Franco was there, [former Steeler] Joe Greene was there, Frenchie was there, all kinds of folks.

“And I asked Franco, Frenchie, and Joe Greene if they would sign it. And we auctioned it off for Transitional Services Incorporated, which is a nonprofit in Pittsburgh that provides dignified housing and sheltered homes for people with intellectual disabilities.”

Silverstein said that signed pass resulted in $1,800 for the nonprofit, where Silverstein’s brother, Lewis Silverstein, who was born with Down’s Syndrome, lived for 25 years.

“ People used to jokingly refer to Franco as ‘Free Meal O’ because if you had an event in Pittsburgh that was doing good, he used his platform to help you.”

It’s for this reason Silverstein hopes he can affect change in Harris’ name, posthumously as it may be.

Silverstein has suggested adding Harris’ name to the Fort Duquesne Bridge.

“ Pittsburgh is a city of Bridges. Bridges unite us and bring us together over the divisions, whether it’s a river or whatever, that would tend to keep us apart,” Silverstein said.

“And no one in my lifetime did more to bring us together as a city than Franco Harris, and I honestly believe that it would be fitting in proper that we rename the Fort Duquesne Bridge, the Franco Harris Fort Duquesne Bridge, and that we do so in April when the NFL Draft comes to town.”

He said he thinks he can make it come to fruition.

“ I’m gonna make a few phone calls,” he said.

“I don’t know if they’ll remember me. But I’m sure they’ll remember Mr. Harris.”