Scientists had a rough year in 2025. As always, experts from all disciplines arrived at some groundbreaking conclusions, a small but critical portion of which we’ve highlighted in our annual Gizmodo Science Fair. But the industry also faced an onslaught of challenges to its credibility and economic worth around the world—especially in the U.S., where administrative decisions cast doubt on the future of key science projects and organizations.

We carry these mixed feelings into 2026, which is slated to be another great—yet perhaps troubled—year for science. No list can fully capture the vast range of the scientific enterprise, but here are some things Gizmodo’s Science Desk is keeping an eye on.

(You’ll notice that we’re missing a ton of spaceflight and astrophysics items on this list, but don’t worry. We’re cooking up an entire list wholly dedicated to that, so stay tuned!)

Giant physics machines go on collective hiatus

Let’s start with the biggest items—literally, in a physical sense. In 2026, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, Switzerland, will officially go on a 4-year break in July. The hiatus is to install major upgrades to the already gigantic detector, which has been instrumental to a sizable chunk of the best discoveries in particle physics. If things go as planned, the LHC will return as the High-Luminosity LHC in 2030.

A look inside the construction of the High Luminosity LHC. Credit: Samuel Joseph Hertzog (CERN)

A look inside the construction of the High Luminosity LHC. Credit: Samuel Joseph Hertzog (CERN)

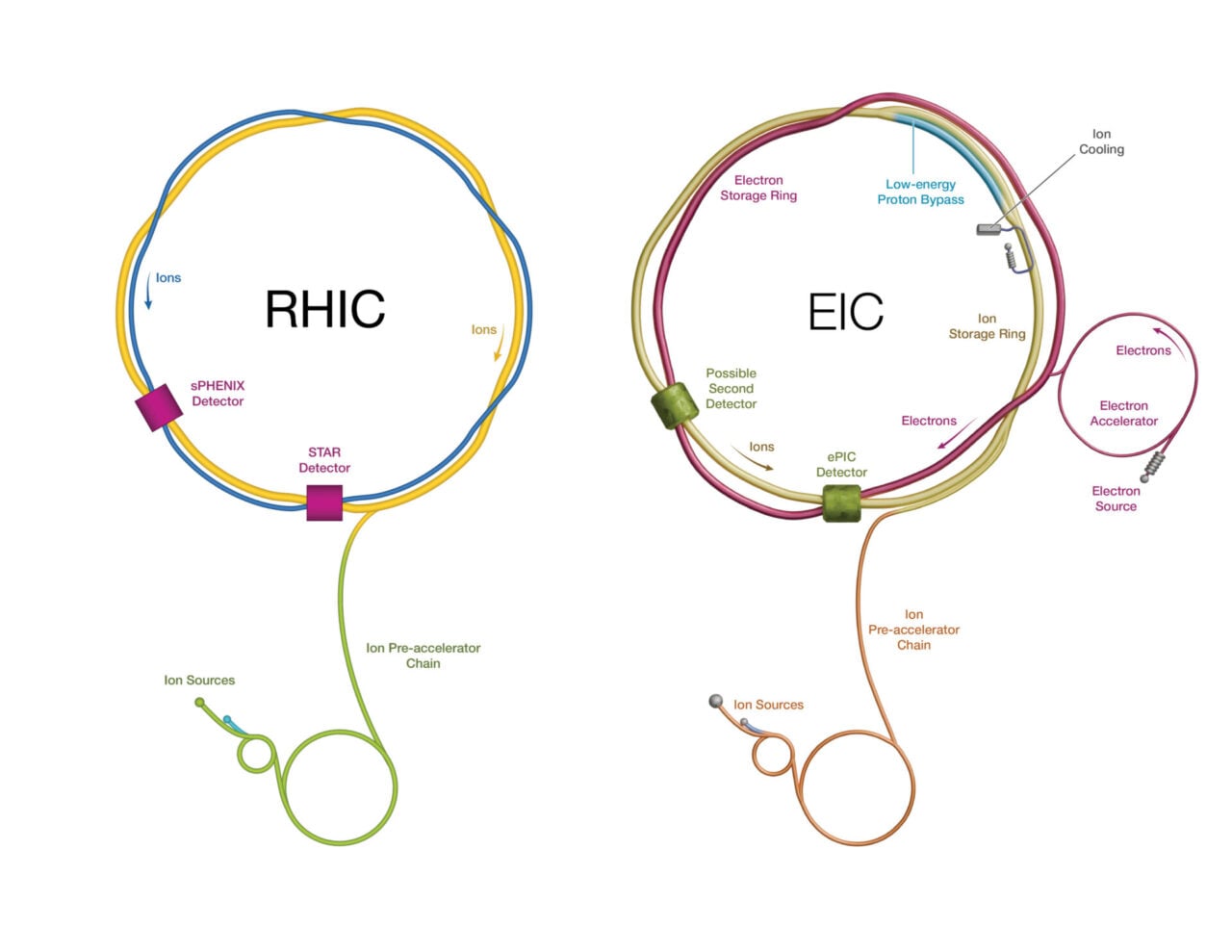

Meanwhile, Brookhaven National Laboratory will bid goodbye to the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), leaving it without a major particle accelerator for the first time in 25 years. This shutdown is also to prepare for upgrades, in this case the Electron-Ion Collider. But Brookhaven hasn’t provided detailed updates on its progress, although it announced one construction milestone in 2024 and successfully secured funding for 2026.

An artist’s renderings of the RHIC (left) and the next-generation EIC (right). Illustration: Valerie A. Lentz/Brookhaven National Laboratory

An artist’s renderings of the RHIC (left) and the next-generation EIC (right). Illustration: Valerie A. Lentz/Brookhaven National Laboratory

Speaking of ambiguity, Fermilab’s muon detector is supposed to be completed by spring 2026, but the Illinois laboratory has yet to share whether that will truly happen.

In quantum computing news…

2025 was a markedly rewarding year for quantum computing. Major stakeholders—AWS, Google, IBM, and Quantinuum, to name a few—ramped up their hardware efforts. Improvements in the physical machines gave scientists room to explore a wide range of theoretical ideas.

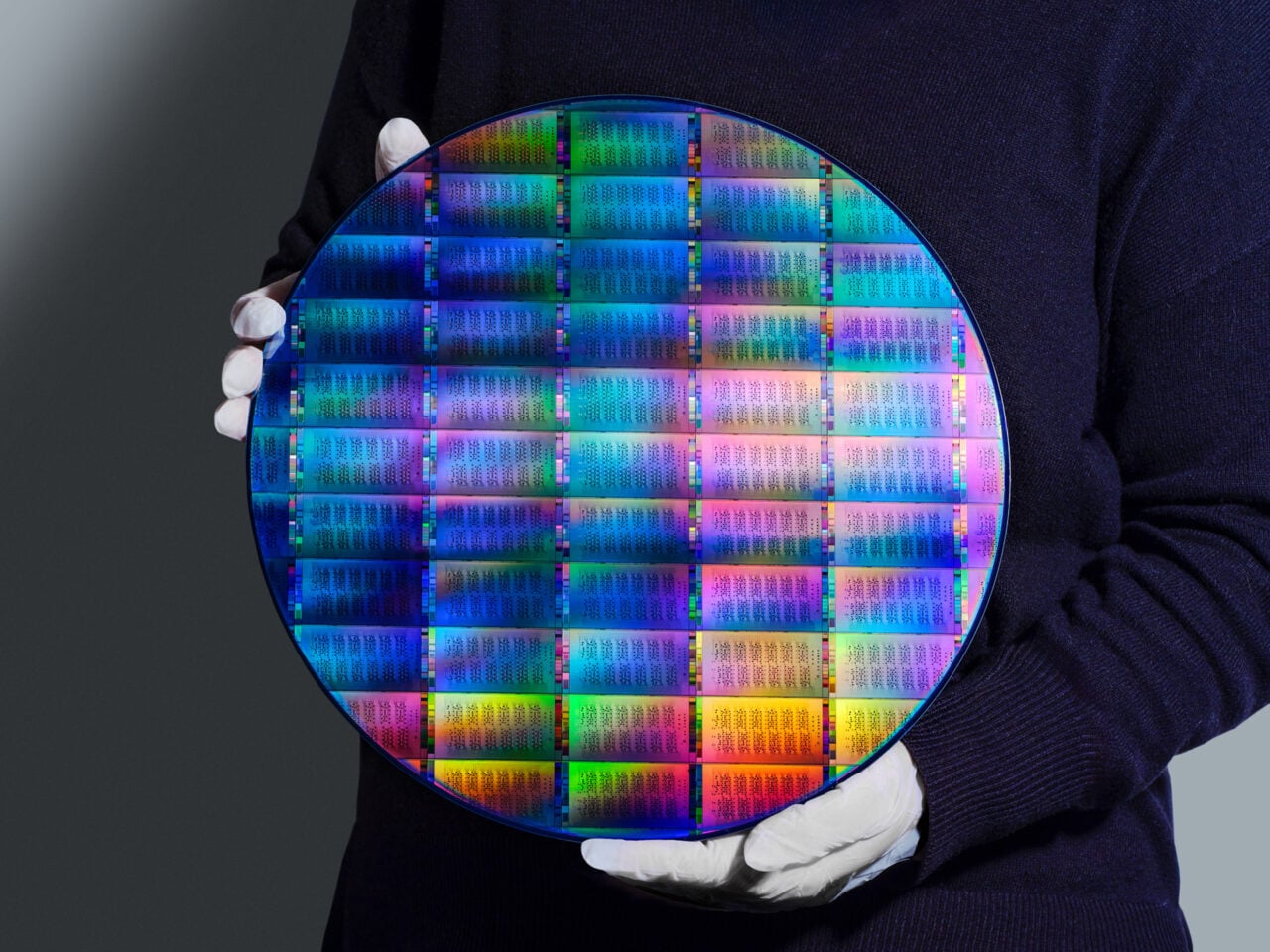

That trend will certainly continue next year—if not intensify—as smaller startups enter the race and larger companies actively look to implement quantum computers in the workplace. Just in the last quarter of 2025, Quantinuum and IBM each unveiled their latest models, Helios and Nighthawk. Once researchers get their hands on these fancy gadgets, who knows what we’ll see?

A close-up of the wafer for IBM’s Nighthawk quantum computer. © IBM

A close-up of the wafer for IBM’s Nighthawk quantum computer. © IBM

In fact, you can take a gander at an open-source list IBM has compiled for quantum advantage, the Quantum Advantage Tracker. “We encourage the entire computing community to contribute to the tracker and test candidates with the best classical methods,” IBM told Gizmodo.

New vaccines, medications

Longer-term trials for new vaccines and medications are expected to arrive in 2026. For example, data from a Phase III trial of a new tuberculosis vaccine might arrive in early 2026, being almost a year ahead of schedule as of mid-2025. We should also hear more about the first clinical trial of pig-to-human organ transplantation, which began late this year, as well as whether the FDA will approve Takeda Pharmaceuticals’ oveporexton, a first-of-its-kind treatment for narcolepsy.

Parade of weight-loss drugs to continue

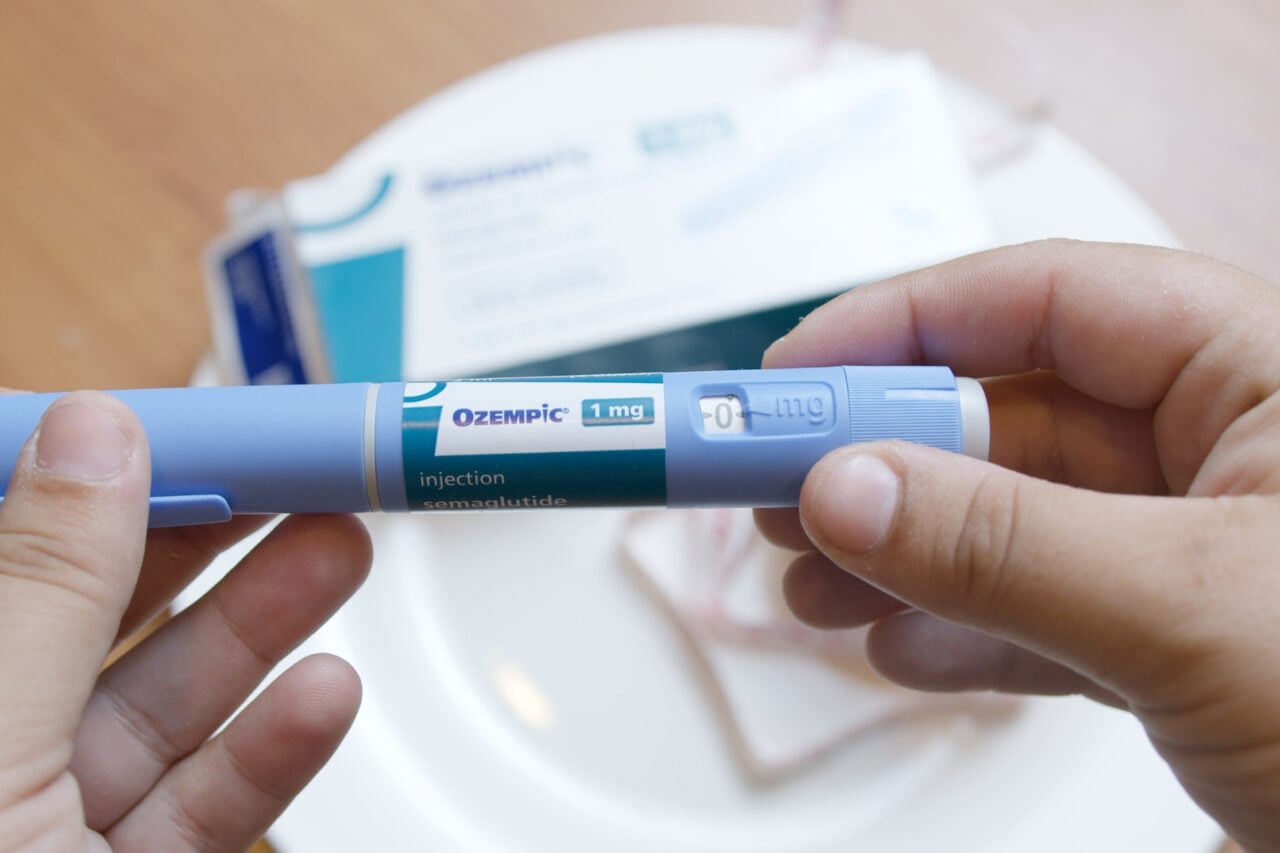

This year was also big for various weight-loss drugs, and the trend should continue into 2026. Eli Lilly, the pharmaceutical company behind recent trials of a wildly successful alternative to Ozempic and Wegovy, will submit a different GLP-1 pill for obesity, orforglipron, for FDA approval sometime next year.

© Starmarpro via Shutterstock

© Starmarpro via Shutterstock

Novo Nordisk’s high-dose semaglutide pill—the active GLP-1 ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy—will likely be approved by the end of 2025 and available next year as well. The company will also seek FDA approval of their next-gen obesity drug CargiSema (a mix of cagrilintide and semaglutide) early next year, with possible approval by late 2026.

That said, don’t be surprised if increased competition and government subsidies lead to significant price drops for weight-loss drugs, which would be good news for consumers.

Rollbacks of protective regulations

Earlier this year, NOAA and the Fish and Wildlife Service proposed rescinding the regulatory definition of “harm” in the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Essentially, the change would limit ESA protections to fish and wildlife themselves—not necessarily their habitats. If the proposal goes through, it could make human construction easier on land occupied by endangered species.

In a similar vein, the Trump administration has been keen to disparage the role of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), rolling back reforms put in place following Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The current administration has also scrubbed climate reports, and the final ruling on repealing the EPA’s “endangered finding” will come next year. These developments may leave the U.S. underequipped for climate disasters to come in 2026.

New year, new plans

2026 marks the first year of China’s next Five-Year Plan, the country’s sweeping blueprint for short-term economic growth. Some highlights include the start of commercial operations for small modular nuclear reactors. These mini reactors, as the name suggests, are smaller in capacity but mobile enough to supply remote regions with electricity.

Drone photo showing the Meng Xiang. Credit: Xinhua

Drone photo showing the Meng Xiang. Credit: Xinhua

In addition, Meng Xiang, China’s drilling ship, will conduct its first scientific mission to drill about 4.35 miles (7 kilometers) into Earth’s crust—deep enough to potentially approach the mantle—and collect valuable samples.

Gene editing may go mainstream

November saw the first-in-human clinical trial results for a gene-editing technique to lower cholesterol and triglycerides in people with lipid disorders, or excess fat levels in the blood. KJ Muldoon, the first known person—a baby—to receive customized CRISPR-based therapy, was selected as one of Nature’s top 10 people who shaped science in 2025. (We are happy to report that the therapy saved his life).

Given these strides, we may actually soon see CRISPR therapies break into mainstream markets. Several CRISPR therapies are entering clinical trials next year, with major pharmaceutical companies investing up to billions of dollars to get ahead of the competition.