Romantasy is in the air—and on TikTok, book blogs and booksellers near you. While the portmanteau—combining the words romance and fantasy—might be new, this genre mash-up has been beloved since the early 20th century. Worldbuilding is as important as the couple’s happy ending, and some publishers have invested making the book itself as its own work of art.

Reviewers define romantasy as a fantasy where the plot falls apart if you remove the romance. This eliminates a classic like “The Lord of Rings”: Despite the extra sparkle in the film adaptation, the love story of Aragorn and Arwen can be deleted as easily as trimming out Tom Bombadil. Fans might not like it but the plot works without either one. In a Bookstr February 2024 post “The History of the Wonderful Romantasy Genre,” author Danielle Tomilson argues that dressing up a standard romance with elves does not a romantasy make. Instead, fantasy worldbuilding is as central to the plot as the love story.

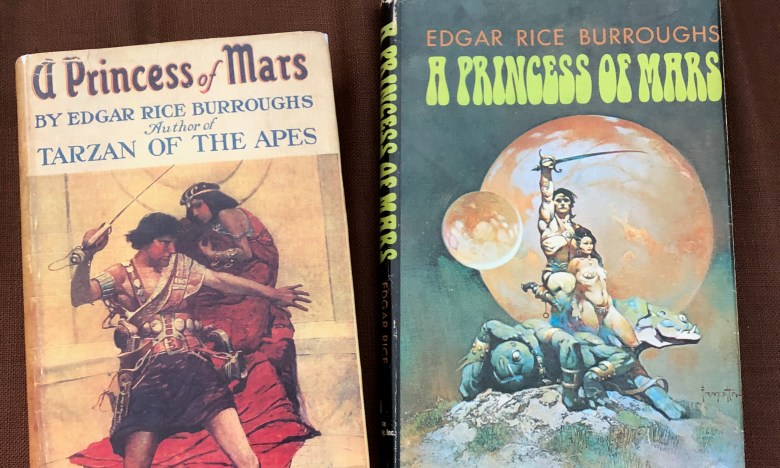

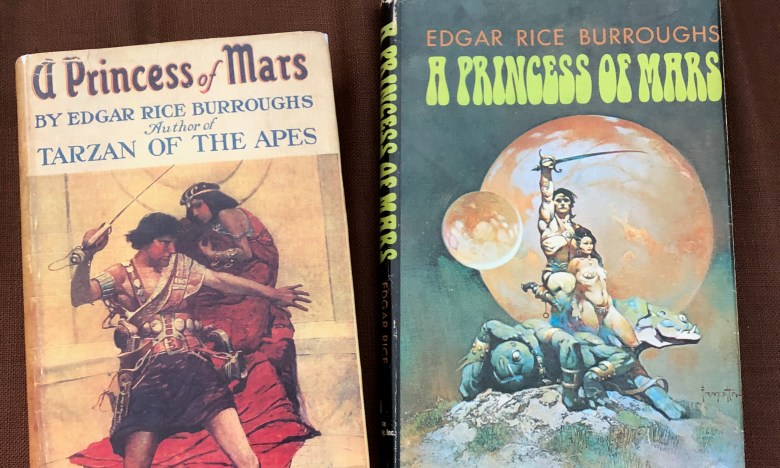

L-R, “A Princess of Mars” by Edgar Rice Burroughs is pictured in a 1917 edition with cover art by Frank Schoonover and a circa 1970 book with artwork by Frank Frazetta. (Rosemary Jones/Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association via Bay City News)

L-R, “A Princess of Mars” by Edgar Rice Burroughs is pictured in a 1917 edition with cover art by Frank Schoonover and a circa 1970 book with artwork by Frank Frazetta. (Rosemary Jones/Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association via Bay City News)

Based on this criteria, Bookstra’s Tomilson starts the genre’s history with author Emma Bull’s “War for the Oaks” (1987). Pamela Patrick’s artwork for the Ace first edition looked more romantic than later printings, which played up the urban gritty part of the plot. The novel fits the idea of trying to lure romance readers and fantasy readers with an appropriate cover. But does “War for the Oaks” really mark the first appearance of the romantasy genre?

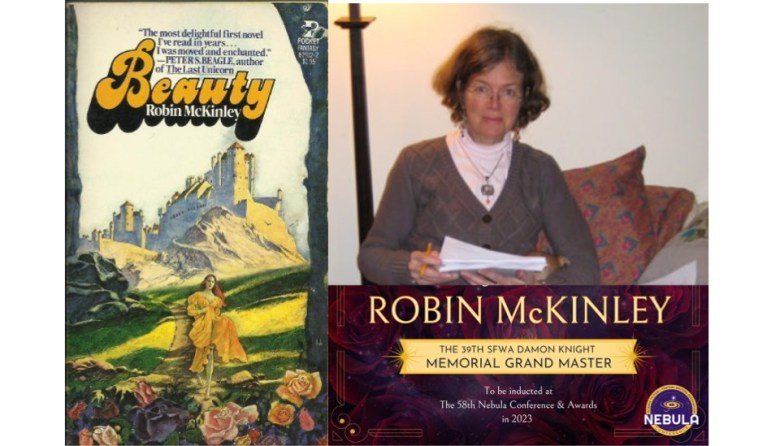

“Beauty” is a 1978 title by Robin McKinley, who served as the 2022 Science Fiction Writers Assocation Grand Master. (Rosemary Jones/Science Fiction Writers Assocation via Bay City News) Credit: SFWA

“Beauty” is a 1978 title by Robin McKinley, who served as the 2022 Science Fiction Writers Assocation Grand Master. (Rosemary Jones/Science Fiction Writers Assocation via Bay City News) Credit: SFWA

Author and 2022 Science Fiction Writers Assocation Grand Master Robin McKinley’s first novel, “Beauty” (1978), also fits Tomilson’s definition. A fantasy with an indispensable love story at its core, the novel contains all the vibes of today’s cozy romantasy, with likable side characters, a horse pal and a hero who owns a gorgeous library. “Beauty” is often cited as the inspiration for other authors’ fairytale retellings, a popular trope in romantasy. For the 1979 paperback cover, Pocket Books’ uncredited wraparound artwork featured a young woman running away from a castle in much the style of paperback gothic romances where ladies fled mansions with a single lighted window.

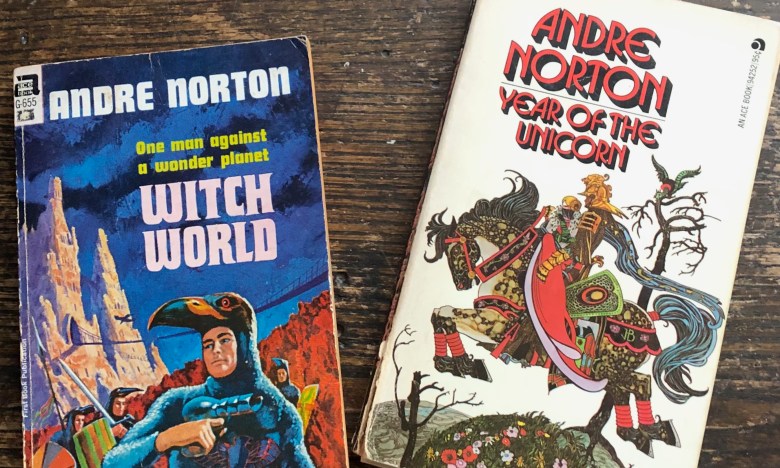

Andre Norton’s 1963 “Witch World” and 1974 “Year of the Unicorn” are romantasy titles.

Andre Norton’s 1963 “Witch World” and 1974 “Year of the Unicorn” are romantasy titles.

So did the 1970s publishers guess there was a market for romantasy even if there wasn’t a word for it? The paperback publishers of the decade certainly put out covers that we would now identify as romantasy in style. Andre Norton’s “Witch World” series started out as science fiction where “the magic is real!” (as blurbed on her early books) and often had a romantic subplot. “The Year of the Unicorn” (1965) reads like today’s romantasy, with exiled shapeshifters claiming brides as payment for their support in battles. While the original paperback featured the Jack Gaughan science fiction art used for the series, Ace’s 1974 reissue went with a gorgeous fairytale illustration by J. H. Breslow of the bride and her knight riding through a flowery field.

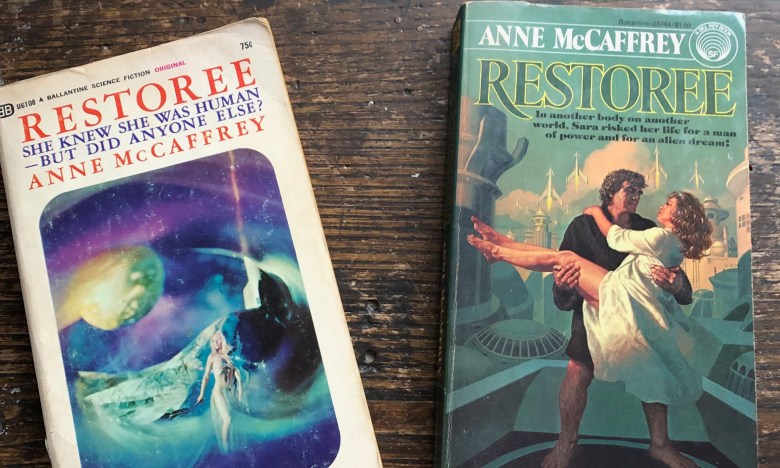

L-R, the 1967 cover of “Restoree” has an uncredited artist, while the 1977 edition features an illustration by the Brothers Hildebrandt. (Rosemary Jones/Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association via Bay City News)

L-R, the 1967 cover of “Restoree” has an uncredited artist, while the 1977 edition features an illustration by the Brothers Hildebrandt. (Rosemary Jones/Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association via Bay City News)

Ballantine’s reissue of “Restoree” (1967) by Anne McCaffrey also played up the romance. McCaffrey’s first novel is filled with space battles but romance is as central to the plot as the alien world. Ballantine’s 1977 paperback cover by the Brothers Hildebrant shows the heroine being swept off her feet (literally) by the alien soldier hero. These reprints got lush cover art treatment as far back as the 1970s, even if they lacked the fancy sprayed edges of today’s romantasy novels. But was anything older marketed as much as romance as fantasy?

L-R, “A Princess of Mars” by Edgar Rice Burroughs is pictured in a 1917 edition with cover art by Frank Schoonover and a circa 1970 book with artwork by Frank Frazetta. (Rosemary Jones/Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association via Bay City News)

L-R, “A Princess of Mars” by Edgar Rice Burroughs is pictured in a 1917 edition with cover art by Frank Schoonover and a circa 1970 book with artwork by Frank Frazetta. (Rosemary Jones/Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association via Bay City News)

The creator behind the legendary Tarzan may have been a godfather of romantasy. Desperately poor, constantly switching jobs and pawning goods to feed his family of five, Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote of other worlds for “mental relaxation.” He made his pulp debut in 1912 with “The Princess of Mars” featuring hero John Carter.

In his first adventure, Carter is transported to a marvelous world full of four-armed green monsters, where he meets an “incomparable” and mostly naked beauty named Dejah Thoris. Burroughs not only wrote a swashbuckling adventure but also kept readers coming back for more love stories with lightly clad Martians! Like “Fourth Wing” by Rebecca Yarros, Burroughs gave his central couple several romantic setbacks to overcome over multiple books. Carter may marry his Dejah Thoris at the end of “Princess,” but he is then whisked back to Earth. After two more books of adventures, they settle happily in their palace and enjoy the romantic adventures of their offspring and friends. Long before the Bridgertons, Burroughs perfected the formula of writing a new romance for each member of an extended family. After bringing together John Carter and Dejah Thoris, Burroughs focused on the couple’s children and friends.

Note how the first hardcover edition of “A Princess of Mars” (1917) featured both John and Dejah in the dust jacket art by Frank E. Schoonover. Schoonover gave readers a much more clothed John Carter and Dejah Thoris than the 1970s dust jacket featuring art by Frank Frazetta. But no matter which Frank you like best, both covers made the couple as obvious as the swashbuckling.

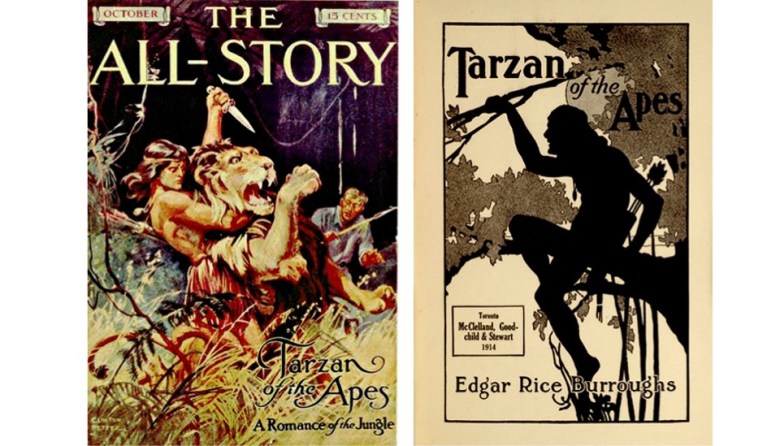

Burroughs also used the same formula with his most famous couple, Tarzan and Jane, who take two books to reach their “fated mates” wedding. Then he wrote a romance for their child in “Son of Tarzan.” At the outset, publishers sold the love story as hard as the adventure: The famous first appearance of “Tarzan of the Apes” (1912) in All-Story magazine is subtitled “A Romance of the Jungle” on the cover. However, his publishers never gave the Tarzan books the romantic covers of the Mars series.

In “Thuvia, Maid of Mars” (1916), their son Carthoris finds his own princess. Never mind the four-armed green giant in the background; the foreground of the pulp magazine cover and subsequent-book dust jacket features Thuvia running through a bank of red flowers. P. J. Monahan’s lovely artwork definitely makes this look like a romantic adventure.

“Romantasy” might be a 21st-century word but luckily for fans, these books go back decades. You’ll find many interesting novels out there, past and present, and of course that gorgeous cover art to add to your romantasy bookshelf!

Rosemary Jones, a member of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association, is a collector who finds romantasy publications with splayed edges and illustrated endpapers a lovely return to the illustrated fiction of an earlier age. Find the original version of this article on SFWA, follow her collecting adventures at lost_loves_books on Instagram and her writing at rosemaryjones.com.

Credit:

Credit: