Title: The z=7.08 quasar ULAS J1120+0641 May Never Reach a “Normal” Black Hole to Stellar Mass Ratio

Authors: Meredith A. Stone, George H. Rieke, Jianwei Lyu, Michael K. Florian, Kevin N. Hainline, Yang Sun, Yongda Zhu

First Author’s Institution: University of Arizona

Status: Published in The Astrophysical Journal [open access]

The first galaxies in the universe emerged out of an archaic age of darkness. Like luminous factories, they started rapidly churning out stars, spilling light into the cosmos. This process of star formation continues to the present day. In some galaxies, it occurred at astonishing rates, with the equivalent of thousands of Suns being assembled in a single year. At other times, it came to a slow crawl, with all fresh reserves of star-building gas seemingly exhausted. Yet when the gears of star formation ground to a halt, certain events were able to send them spinning again.

One of the most spectacular of these is a merger, a train-wreck collision between two galaxies. Images of these events are often breathtaking, showing arms of light twisting together and vast stellar streams being violently cast away. Mergers directly increase the stellar mass (the mass of all stars) of galaxies by combining two into one. The intense gravitational interactions between the galaxies involved can also disrupt stagnant pools of gas, igniting a new burst of star formation. Thus, interactions between galaxies can be a significant driver of their growth.

Sometimes, a reservoir of matter is driven towards the center of a galaxy due to a “secular” process (one that occurs without external intervention) or from a merger. At the galactic nucleus, the infalling streams of matter encounter a supermassive black hole (SMBH). The matter falls into a swirling accretion disk, heating to extreme temperatures and furiously glowing. If the black hole is massive enough and the gas falls in quickly enough, the accretion disk can outshine all of the stars in the galaxy, and we call such a source a quasar. The intense radiation produced by a quasar can impact the entire rest of the galaxy, either suppressing the formation of new stars or sometimes igniting it.

Thus, a galaxy has an important role in the growth of its central SMBH, and vice versa. This connection manifests in complicated ways. Most strikingly, it is thought to be the cause of the correlation between a galaxy’s stellar mass and its SMBH mass. In the nearby universe, galaxies have stellar masses around a thousand times more than their black hole masses. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), our most powerful tool for investigating early galaxies, has given us unprecedented insight into whether this holds up in the distant universe. Though the jury is still out, many researchers are convinced that the answer is a resounding no. We’ve found distant black holes that appear to be nearly equal in mass to their host galaxies, something that’s unfathomable in the local universe.

However, this raises a key question. Black holes and their galaxies grow together, and they started on nearly equal footing. So why do all of the galaxies in the nearby universe appear so much more massive than their black holes? Today’s paper underscores this puzzle, pushing it to the breaking point. The authors examine a well-studied quasar, ULAS J1120+0641 (hereafter J1120), which we see as it appeared just 750 million years after the Big Bang. This source has a SMBH with an astounding 20% the mass of its host galaxy. The shocking part is that, carefully accounting for all of the ways this galaxy could grow in the future, there appears to be no way for J1120 ever to reach “normal” proportions.

First, the authors analyze the key observations of J1120 obtained to date. In addition to observations from JWST, this source has been targeted by some of the most powerful astronomical facilities, including the Hubble Space Telescope (optical and near UV), the Chandra and XMM-Newton Observatories (X-rays), the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (radio/millimeter), and numerous other ground-based telescopes. This incredible dataset provides a detailed picture of J1120 across the electromagnetic spectrum, spanning X-rays to radio emission.

The authors compare various measurements of the black hole’s mass and find that multiple methods yield a similar result of about a billion and a half times the mass of the Sun. Turning to the host galaxy, they estimate the mass of the visible stars, which is more complicated than it sounds – you can’t exactly count them, since the enormous distance between us and J1120 causes it to appear as just a fuzzy blob. They combine this mass with the mass of newly-forming stars that are buried in dust and obscured from our view. The mass of a nearby galaxy that’s actively merging with J1120 is added to this sum. Finally, the authors compute how many stars could form in the future from all of the gas left in the galaxy, and throw this into the total.

Even with all of these components, the host galaxy would only be ten times more massive than the black hole at the center. This ratio is a far cry from the factor of a thousand we expect for normal galaxies in the local universe!

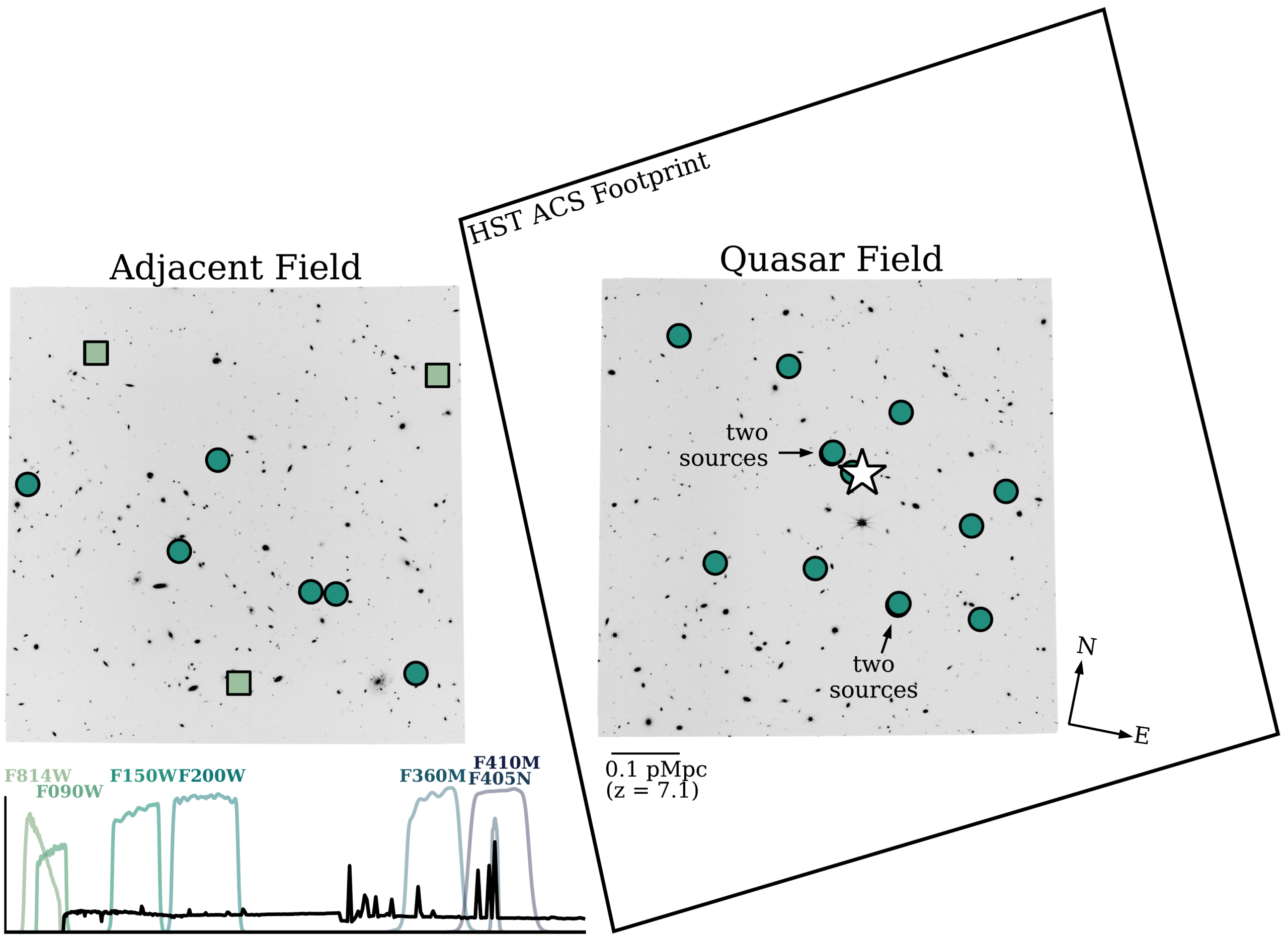

Well, if one merging galaxy won’t do it, what if J1120 merges with literally every single other nearby galaxy? The authors use new JWST data to count all sources near the quasar (Figure 1) and measure their stellar masses. Going further, they estimate how many galaxies their technique may have missed and add all of these to the pile. Not done yet, they finally conclude by making a rough approximation of how much loose gas is in these nearby galaxies, and compute how much extra mass could exist in stars born from this fresh material. Assuming that J1120 survives the full-frontal assault, being battered by mergers from each of its neighbors in turn, its total stellar mass would grow by quite a large factor.

Figure 1: All of the galaxies found by JWST that are close enough to J1120 to potentially merge with it in the future. The circles mark confident detections, whereas the squares represent galaxies for which the exact distances couldn’t be confidently measured. What would happen if all of these crashed into J1120? Figure 2 in today’s paper (Stone+2025).

Figure 1: All of the galaxies found by JWST that are close enough to J1120 to potentially merge with it in the future. The circles mark confident detections, whereas the squares represent galaxies for which the exact distances couldn’t be confidently measured. What would happen if all of these crashed into J1120? Figure 2 in today’s paper (Stone+2025).

What’s the final result? Shockingly, even after all of this growth, the stellar mass of J1120 would still only be about 40 times that of the central black hole. That’s 25 times less than we’d expect from a nearby galaxy! Even if the black hole never grows again, it appears that this galaxy will never reach “normal” proportions. So why is it that, when we look around at the local universe, there’s nothing like J1120? The authors point out that galaxies near J1120 would be missed by their methods if they are obscured by thick shrouds of gas and dust. Such sources would increase the estimated mass that could be contributed by mergers. On the other hand, maybe J1120 will adopt the strategy of the blue whale, filter feeding on the extremely sparse matter between galaxies, yet growing to enormous proportions.

A fascinating final possibility is that galaxies like this one do exist in the nearby universe. With their black hole switched off, all we would be able to see is a relatively small package of stars. Place such an object far enough away, and we might miss it entirely! Whether galaxies like J1120 achieved normal proportions through unknown mechanisms or are lurking in the far fringes of the local universe, studies like this one shine light on the amazing connection between black holes and their host galaxies. In the future, they will be one key piece in the puzzle of the endlessly complicated past of our own galaxy and the universe at large.

Astrobite edited by Will Golay

Featured image credit: NASA’ Goddard Space Flight Center’s Conceptual Image Lab

I’m an Astronomy graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin working with Steven Finkelstein. I use data from the James Webb Space Telescope to study the formation and growth of the first galaxies and black holes in the universe. In my spare time, I enjoy playing piano, reading, and making YouTube videos.