(Credits: Far Out / Harry Chase / UCLA Library)

Tue 30 December 2025 8:28, UK

Some of the best pieces of the music industry have been about competition. Although music isn’t generally known as a sport, the best times artists push themselves tend to come from moments where they think they can outdo whatever has come before them. While Pete Townshend had his own distinct lane as part of The Who, he believed one band had better communication with their audience than he ever could.

Since the group’s inception, Townshend has always looked to push the boundaries of what a traditional rock band should do. First kicking up the volume to unheard-of levels, songs like ‘My Generation’ would end up defining the sounds of punk rock to come, with Townshend penning lyrics about hoping that he died before he got old.

Once he started directing his music outward, Townshend saw the potential for what music could do outside of just three chords. Across the band’s next albums, the guitarist would habitually put different song fragments together, making for mini-operatic moments on songs like ‘A Quick One While He’s Away’ and ‘Rael’.

Everything would be building towards the band’s first major concept album, Tommy, which saw Townshend using every musical bone in his body to tell the story of a deaf, dumb, and blind kid that gets millions of people interested in the power of rock and roll and his affinity for playing pinball.

What Townshend recognised was that the connection went beyond the songs themselves. The Grateful Dead treated each performance as a shared experience rather than a presentation, allowing the audience to feel like participants instead of spectators. That sense of openness stood in contrast to the carefully structured worlds Townshend was building, where meaning was delivered rather than discovered collectively.

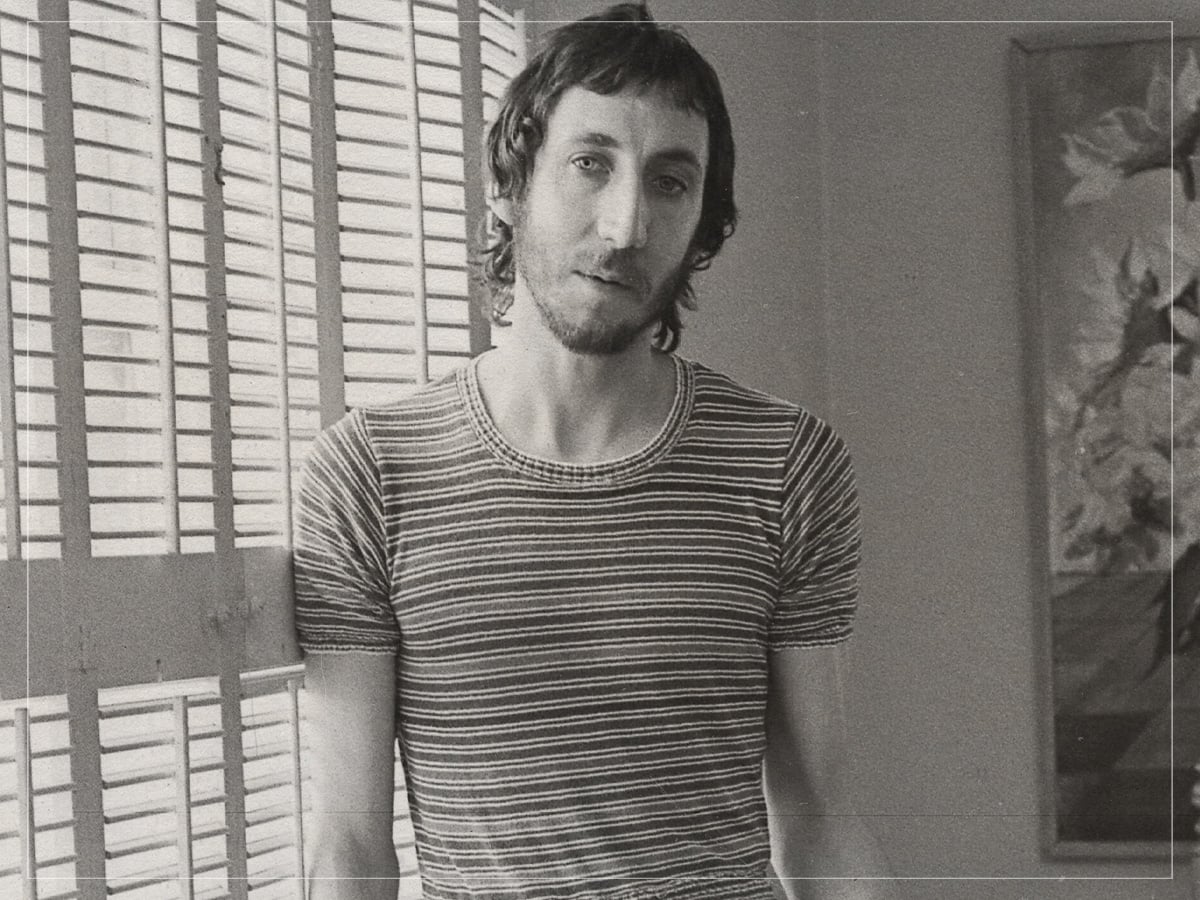

Pete Townshend thrashing in his younger years. (Credits: Bent Rej)

Pete Townshend thrashing in his younger years. (Credits: Bent Rej)

The difference was philosophical as much as musical. Where Townshend focused on narrative and intention, The Dead thrived on spontaneity and trust, letting moments unfold without a fixed destination. It was a reminder that communication in rock music did not always require explanation or structure, sometimes it only needed space for the audience to step inside.

While Townshend celebrated the album as a watershed moment in his songwriting career, not every audience member was on board for the stage production. Instead of being able to tell the story from start to finish live, most of the shows involved the band doing a punctuated version of the album, covering all of the melodic themes before bringing it to the stirring finish on ‘We’re Not Gonna Take It’.

As much as Townshend may have wanted to connect with the audience on a deeper level, the Grateful Dead were already relating to their audience through their relentless jamming. Rather than cater to the pop crowd, The Dead often stretched out their songs live, working in communion with each other and letting every audience member feel part of the communal experience when they played.

Recalling the 1960s rock scene later on, Townshend would talk about how jealous he was of the rapport that The Grateful Dead had set up with their audience, saying, “The commitment of their fans was something that was interesting. They were real contemporaries of the band, and they were a challenge in a sense because they had a connection with their audience that I was envious of”.

While Townshend may have relished what Jerry Garcia was able to communicate with his audience, he did eventually find ways to twist his narrative to serve his audience better, including the massive movies that went along with Tommy and its twin rock opera, Quadrophenia. Townshend didn’t want his audience at arm’s length, but by looking at the way the Grateful Dead worked, he saw what a rock band could be outside of looking like musical gods onstage.

Related Topics