Image credit: © Sam Navarro-Imagn Images

In the top of the first inning on July 3, 2024, Mitchell Parker struck out Francisco Lindor on four pitches: a four-seam out of the zone followed by three straight whiffs on the splitter. He faced Lindor again in the top of the third, and this time it took him six pitches to induce an easy groundout. He mixed in one curveball, but otherwise stuck with the four-seam and split. In the top of the fifth he faced Lindor a third time. Parker started him off again with the splitter, getting another whiff—Lindor’s fourth against it that day. On the next pitch he went back to it but missed the zone, then missed again with the four-seam before dropping in his second curveball of the game against Lindor for strike two. The fifth pitch of the at bat was another splitter, which the All-Star was able to lay off of once more, drawing the count full. Lindor had now seen each of Parker’s offerings multiple times. The splitter was no longer fooling him, and his lineup mates Tyrone Taylor and Mark Vientos had each taken the four-seam deep earlier in the game. That left only the curveball. Parker didn’t quite hang the pitch, but it stayed up just enough for Lindor to pick it up out of hand, track it, and launch it 107 mph into the Mets’ bullpen for a two-run home run.

This was a somewhat familiar sequence for Lindor, who in 2024 saw the most improvement of any batter in baseball, the batter equivalent of the Times Through the Order Penalty (TTOP). It’s a skill that not only exists, but is as sticky year to year as a hitter’s BABIP and is positively correlated both to one’s overall skill as a hitter and specifically to one’s plate discipline. This discovery was prompted by a message from Davy Andrews of FanGraphs in response to a piece I wrote in February. In that research I found the Times Through the Order Penalty for pitchers was primarily due to familiarity rather than to fatigue, and that familiarity came both through a batter’s familiarity with a specific offering from the pitcher and from the pitcher as a whole. After it was published Davy reached out to me with an interesting question: If TTOP is primarily due to familiarity, then shouldn’t we see some variance among hitters in their ability to “learn” a pitcher? And if we do, then what other skills might this “TTOP skill” be associated with?

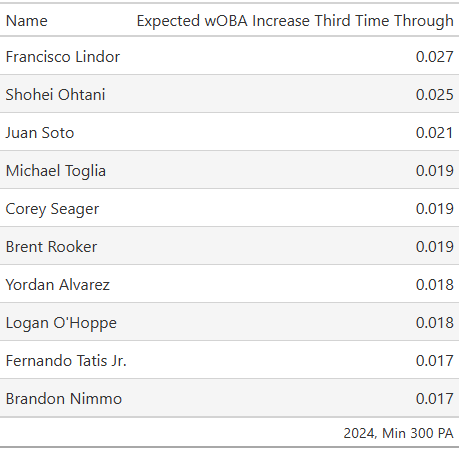

It’s one of those questions that seems obvious in hindsight and yet didn’t occur to me at all in the course of the research. Luckily, answering that question required only a small tweak to the model I used for the previous work. As a refresher, that model predicted the outcome of a plate appearance based on the batter, pitcher, ballpark, team defense, pitch quality during the at bat, and the number of times through the order it’s been. This time I would use PitchPro specifically to capture pitch quality, and I would add a batter-specific TTOP adjustment. This adjustment would look for this batter TTOP skill while controlling for the other factors and the noise inherent in a random sample of at bat outcomes.[1] Running the model for the 2024 season produced the following names at the top of the leaderboard (min 300 PA).

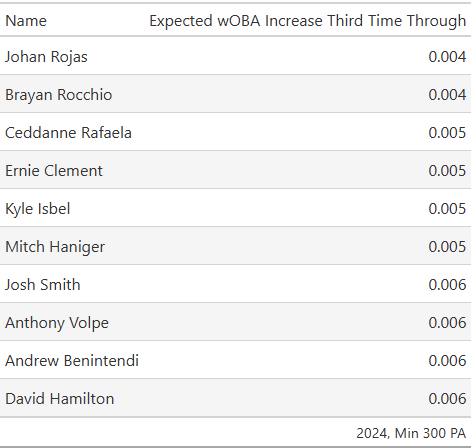

As mentioned, Lindor leads the way, with a 0.027 expected wOBA improvement the third time through relative to his first time facing that pitcher. Followed closely behind was Shohei Ohtani, with Juan Soto, Michael Toglia, and Corey Seager coming right after. If you scanned this list you’d notice not only some of the best hitters in baseball, but also guys who are known for having exceptional eyes and approaches. Juan Soto and Corey Seager in particular are known for these qualities, with the latter even getting his own stat named after him. Additionally, a scan of the guys at the bottom reveals the opposite: below average hitters and those with below-average approaches.

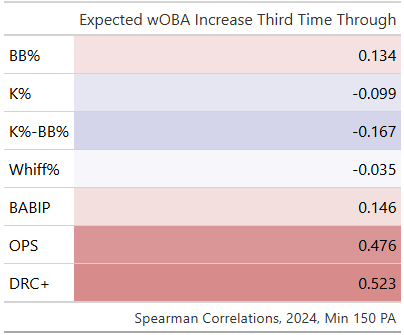

Looking at the full sample this is a familiar pattern. Below is a correlation matrix between this TTOP skill and some familiar hitting metrics. The positive correlations between the plate-discipline-related metrics and TTOP skill are what I would have expected, as both represent the ability to quickly absorb visual information.

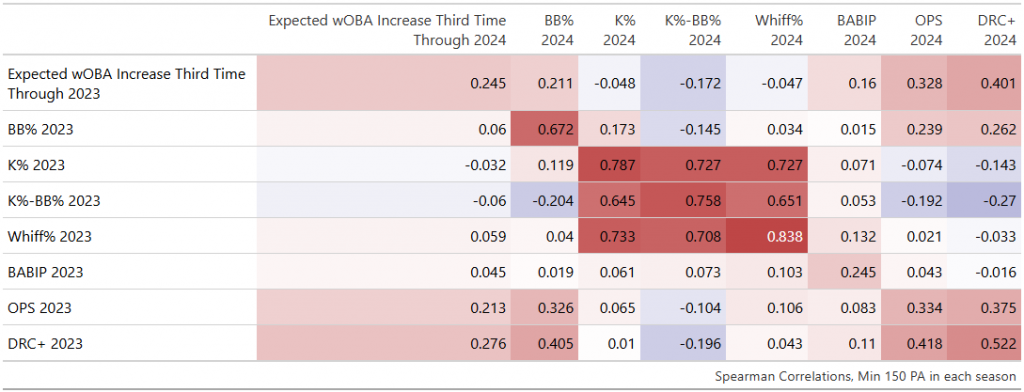

We also see extremely strong correlation between TTOP skill and OPS and DRC+. Some of the correlation between overall outcomes and TTOP skill is tautological: if you improve a lot the third time through the order then of course it’s going to increase your OPS, and thus of course it’s going to result in a positive correlation. However, when we look at how well a stat in one season predicts TTOP skill in the next we again see OPS and DRC+ near the top, and the plate-discipline numbers losing some explanatory power.

This correlation between one’s overall skill as a hitter and one’s ability to adapt to a pitcher within a game speaks to something more general about hitting. Namely, that it’s hard to condense what makes the great hitters great into a set of individual skills. Strength, coordination, and sharp vision are important, but TTOP skill reveals something beyond a good set of eyes and intuition. To improve with familiarity a batter must, in a fraction of a second, not only absorb the new information and integrate it with what he’s already seen that day, but also organize his body to adjust to that information mid-swing. No matter how much better we get at measuring a hitter’s tools, we may never be able to capture their value as strongly as something like StuffPro does for pitchers. Pitches are nice and visible; so much of the hitter’s process is locked away inside their head.

Note finally that while TTOP skill’s correlation to itself isn’t as strong as walk rate or OBP, it does exhibit similar year to year correlation as BABIP, which we know batters have moderately strong influence over based on how hard and at what angles they hit the ball. Similarly, the year-to-year correlation of TTOP for pitchers after controlling for PitchPro is nearly zero. This was the one thing that somewhat surprised me during this study. As mentioned in the previous piece, we know that some of the familiarity penalty is due to a batter’s familiarity with a specific offering from that pitcher, and as such we’d expect those with more pitches to consistently have a smaller TTOP than those with fewer. Additionally, our Arsenal Metric research pointed to more cohesive arsenals better resisting batter familiarity, so we would have expected the year to year stability of these two factors to lead to some year to year stability in TTOP. However, no matter what sort of innings filters weights or limits I applied, I simply could not find a strong signal associated with a specific pitcher.

That sequence of at-bats against Mitchell Parker was one of six times in 2024 that Lindor took a pitcher deep after striking out in his first at bat against them. Charlie Morton, Tyler Glasnow, Ryne Nelson, Kutter Crawford, and even Garrett Crochet fell victim to that old saying in Tennessee: “Fool me—you can’t get fooled again.”

[1] exp_woba ~ 1 + PitchPro + (1|tto) + (1+tto|batter) + (1+tto|pitcher) + (1|home_team) + (1|pitching_team) with exp_woba replacing actual wOBA weights for balls in play with the expected wOBA value of each ball in play based on its launch angle, exit velocity, and estimated spray angle.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.