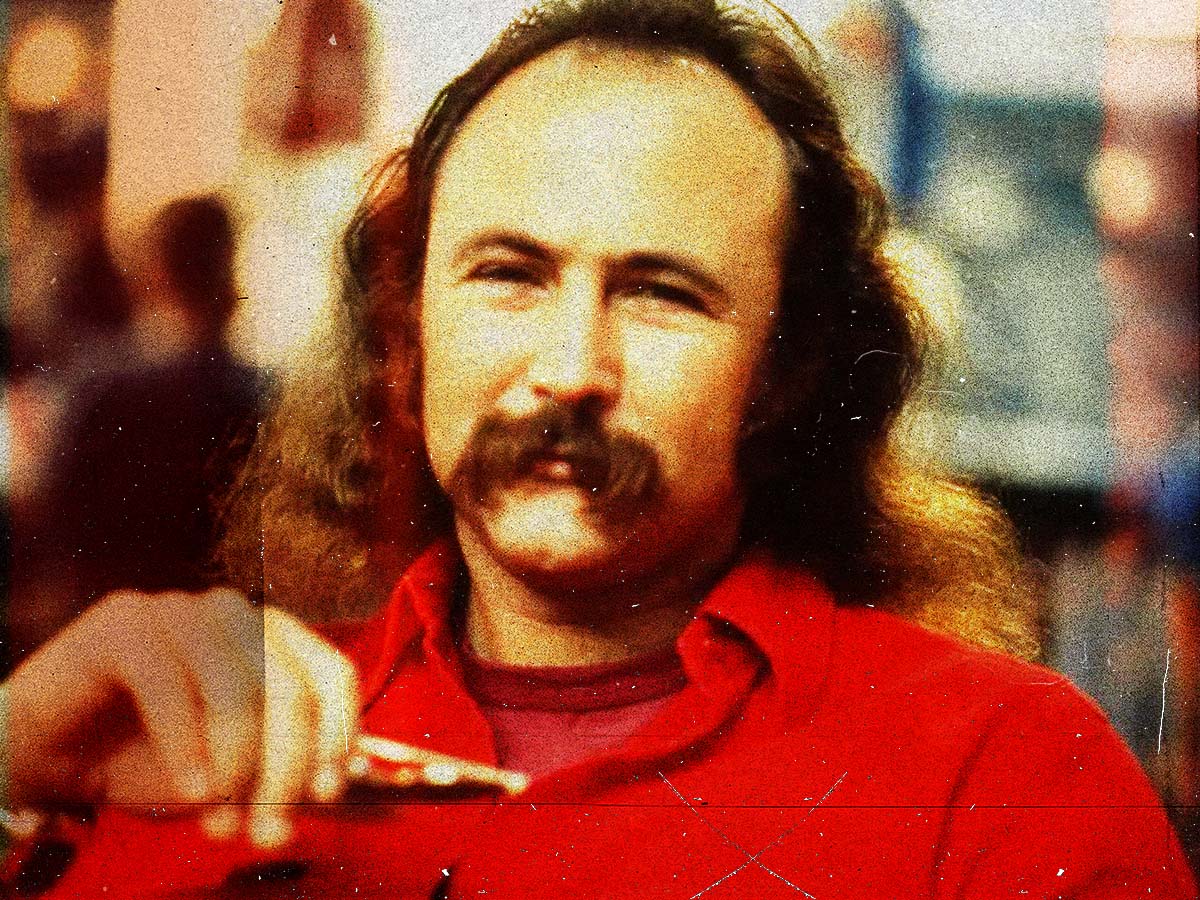

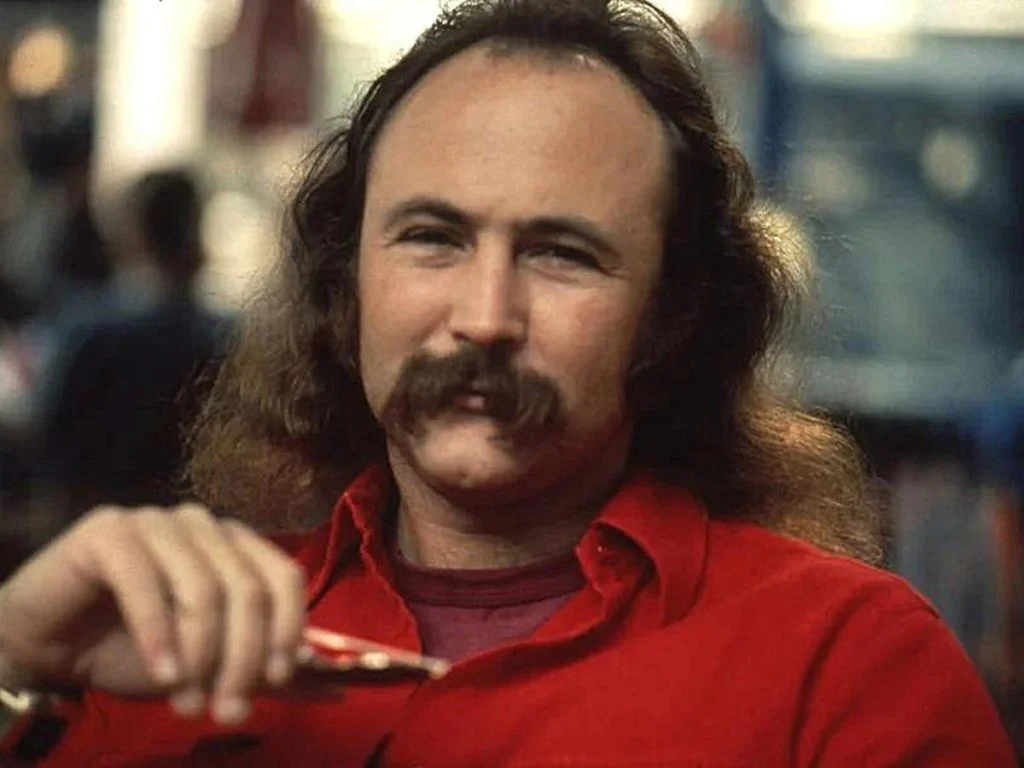

Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

Sat 3 January 2026 15:23, UK

At the height of his drug addiction, David Crosby was caught by police backstage in a Dallas nightclub freebasing cocaine with a propane tank in one hand, a brown bottle in the other, and a .45-caliber semiautomatic in his possession. That’s a potent mix for a freewheeling folk hippie.

He was arrested and sentenced to five years in jail, a matter that he later claimed he didn’t regret. But at the time, things only got worse after he appealed the charge. He was soon pulled over by police, who spotted him driving his motorbike erratically, and he was found to have cocaine and heroin on him. So, with a sentence looming, he was ordered to attend a drug rehab program, which his girlfriend later helped him to escape from.

However, after his daring getaway, he was arrested again, this time in New York City. Unlike Kurt Russell, there was no escaping New York on this occasion. The wayward folky finally had to face the music. After serving a few brutal months in jail, during which he was subjected to solitary confinement as a punishment for “bad behaviour”, he was released on bond while launching an appeal.

Eyeing up further jail time following scheduled hearings, Crosby decided to become a fugitive. However, after six weeks as an outlaw, he turned himself in, set about getting sober in jail, and plotted his return to music. He vowed to a judge that he would never darken the doors of their courtroom ever again—instead, he’d go back to writing some of the world’s most beautiful songs, like ‘Déjà Vu’ that had come before. But he needed inspiration to do so, and looking back was more than a tad painful.

For Crosby, the collapse was not sudden but cumulative. Each arrest, relapse, and escape chipped away at the romantic image of the outlaw musician until only consequence remained. The mythology he had once lived inside began to feel hollow, replaced by a growing awareness that survival would require something sturdier than bravado or rebellion.

Music, however, still represented that possibility. Even when his life was spiralling beyond recognition, songs remained a place where meaning could be rebuilt rather than destroyed. Crosby was not looking for escape so much as alignment, a way to imagine himself as something other than the sum of his worst decisions.

One song proved vital on his tempestuous journey towards sobriety: Steely Dan’s ‘Deacon Blues’. Loosely based on Alfred Bester’s 1952 novel, The Demolished Man, the classic Aja track delves into the psyche of a troubled soul imagining his own spiritual evolution. Crosby was trying to envision something similar himself. Although the song arrived in 1977, ten years before he avowed sobriety in a thank you letter to the judge who sentenced him, the track served as a beacon for Crosby throughout the dark depths of his struggle.

“I let drugs become the most important thing in my life—more so than making music, more so than almost anything,” Crosby told American Songwriter. “But somehow the music hung in there for me and it’s what kept me alive. I was listening to this song an awful lot at that time because it’s spectacularly strong: ‘They call Alabama the Crimson Tide / Call on me Deacon Blue.’ That whole record [Aja] helped me stay alive at that point.”

This affection stayed with Crosby throughout his life. In 2020, the late folk great proudly proclaimed: “Steely Dan is my favourite band in the world period.” In the end, he even got his dream of collaborating with the band. “I worship them because of the writing,” he told NPR. “Donald and Walter were two of the best writers that ever laid a pen on paper. They’re just incredible musicians, and incredible poets, and they just really, really did my favourite music. […] Aja and Gaucho are in my top ten records of my life, both of them.”

He was moved not only by the resonance of the writing but the musical perfection, too. That partyl came from the fact that it resonated with the band too. They’re playing at their most soulful, embodying the sense of musical salvation that the track embodies in an almost postmodernist sense. As Walter Becker explained on Classic Albums, “’Deacon Blues’ is about as close to autobiography as our tunes get. We were both kids who grew up in the suburbs, we both felt fairly alienated. Like a lot of kids in the ’50s, we were looking for some kind of alternative culture, an escape from where we found ourselves.”

With a sense of drive and purpose, the music dovetails with that sentiment perfectly. David Bowie once said, The lyrics taken on their own are nothing without the secondary sub-text of what the musical arrangement has to say, which is so important in a piece of popular music. It makes me very angry,” he explained, “when people concentrate only on the lyrics because that’s to imply there is no message stated in the music itself, which wipes out hundreds of years of classical music.”

In ‘Deacon Blues’, there is a beautiful tessellation between them. That sense of harmony and excitement was what Crosby was looking for his whole life—and hearing played back near enough saved him.

Related Topics