The new year has started in much the same way as the last one ended: with a lot of talk about bubbly valuations. The fact the S&P 500 hit an all-time high this week, didn’t help.

But how do you value what is undoubtedly the stock of the decade?

Nvidia, the world’s most valuable company, has seen its share price rise over 3,000 per cent since the start of 2020. It’s now worth $4.5tn.

But is it really?

The company has risen from being the leading maker of semiconductors for gaming consoles to being the leading processor for bitcoin mining and, now, the poster child of AI.

These successes spring from the decision by founder and chief executive Jensen Huang many years ago to use parallel processing of data, which made Nvidia’s chips faster and more energy efficient than its rivals.

Recommended

More recently that has made them the first choice for AI “training” — giving Nvidia power to raise prices and lifting operating margins from the mid-teens a decade ago to about 60 per cent last year.

The company should make an operating profit of more than $120bn this year — more than the total value of all but the four biggest FTSE 100 companies. Its recent $20bn deal with AI chip start-up Groq is expected to help maintain its position in the high specification part of the market.

But are its shares now too expensive? (Spoiler alert: we don’t own Nvidia.)

The first consideration is the competition. It may help to think of Nvidia chips as high-end sports cars. Great if you want huge power. But it’s dangerous to assume AI’s future is dependent on all that roar and thrust.

When the Chinese DeepSeek AI engine appeared last year, Nvidia’s shares sold off sharply, as DeepSeek’s results seemed comparable with those of OpenAI (Nvidia’s largest client) and apparently involved fewer expensive, high-end chips. DeepSeek has started 2026 with a research paper offering a more efficient way of training large language models, which may further reduce reliance on the most powerful chips.

Alphabet has developed its own Tensor chips (think decent saloon car). Only a couple of months ago it launched its Gemini 3 AI model, powered by these. Elsewhere, Anthropic AI relies largely on chips designed by Alphabet and Amazon (AWS).

The Gemini 3 and Anthropic models both outscore OpenAI’s ChatGPT in some criteria. This helps explain the 60 per cent rise in Alphabet’s share price last year. (I confess that we missed much of this, wrongly believing Alphabet would be challenged by AI and the Department of Justice probe. We have remedied this now.)

In valuing Nvidia you can’t ignore OpenAI. Nvidia intends to supply its client’s data centres with over $100bn of Nvidia chips. It’s too cynical to regard this arrangement as part of a “Ponzi scheme”, which some have done — it’s sensible to back important commercial partners. But OpenAI isn’t expected to make an actual profit this decade, so we count this element of Nvidia’s future income as part revenue, part loan.

Next up is the energy issue. The current “training” phase for AI chips involves them learning patterns in huge datasets and uses massive amounts of electricity. And there’s the rub. Power limitations could pull the plug on the heady revenue growth numbers underpinning many AI stock forecasts. There are no easy solutions. Build an adjacent gas turbine? Sorry, manufacturers have sold out even before you apply for planning permission. Some data centre companies have begun repurposing jet engines, but this looks an expensive workaround.

If Anthropic floats on the Nasdaq this year it will be valued on hoped-for future cash flows. Power constraints could undermine sales and hit those valuations substantially. It’s a good illustration of how a stock market boom can peter out when exposed to the dull light of reality.

Valuing semiconductor stocks is always tricky. An old mate of mine compares it with valuing cement companies — both industries are capital-intensive and cyclical. These are not buy-and-hold stocks. Buy them at the bottom of the cycle and sell at the top.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, when their earnings have plunged, their share price/earnings ratio may look ridiculously high for a while — that’s when you buy. Similarly, low-looking price/earnings ratios come at the cycle peak, so you sell when price/earnings ratios look low.

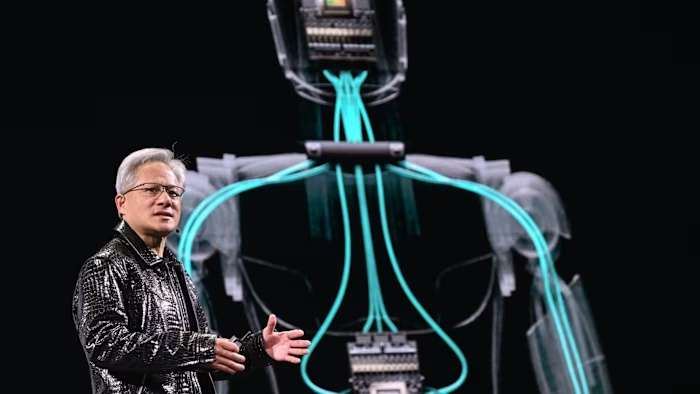

Nvidia outsources the manufacturing of its designs, thereby avoiding the eye-watering capital costs of building fabrication plants. So it’s less capital-intensive than it might be. And AI should keep chip demand — and therefore sales — growing for a while. Huang’s speech in Las Vegas this week focusing on the power of Nvidia’s latest chips and its role in robotics may have reassured some investors that sales growth will continue, but if margins have peaked that could have little impact on profits.

To my mind, the AI boom is moving to its next phase, which could benefit other AI-related stocks we own, such as Broadcom and Taiwan Semiconductor. These have been doing nicely. We also have sizeable holdings in Alibaba and Baidu, Beijing’s AI champions.

Apple, which we bought a few months ago, appears to be leaving the big spenders to develop the cutting-edge stuff, using more third-party AI technology within its products. This hybrid strategy could prove smart.

Some so-called “AI losers” could turn a corner in 2026. Software companies, such as holdings Salesforce and SAP, have been seen as threatened by AI, but it could instead enable them to enhance significantly what they offer.

The year ahead will be interesting. I’ll undoubtedly have got some of this wrong — I wasn’t taught divination at school. But over the years I’ve found buying sensible stocks at a sensible price and diversifying is a reliable investment strategy. I like Nvidia, but I don’t think it’s a sensible price. And I think there are better alternatives from an investment perspective.

Simon Edelsten is a fund manager at Goshawk Asset Management