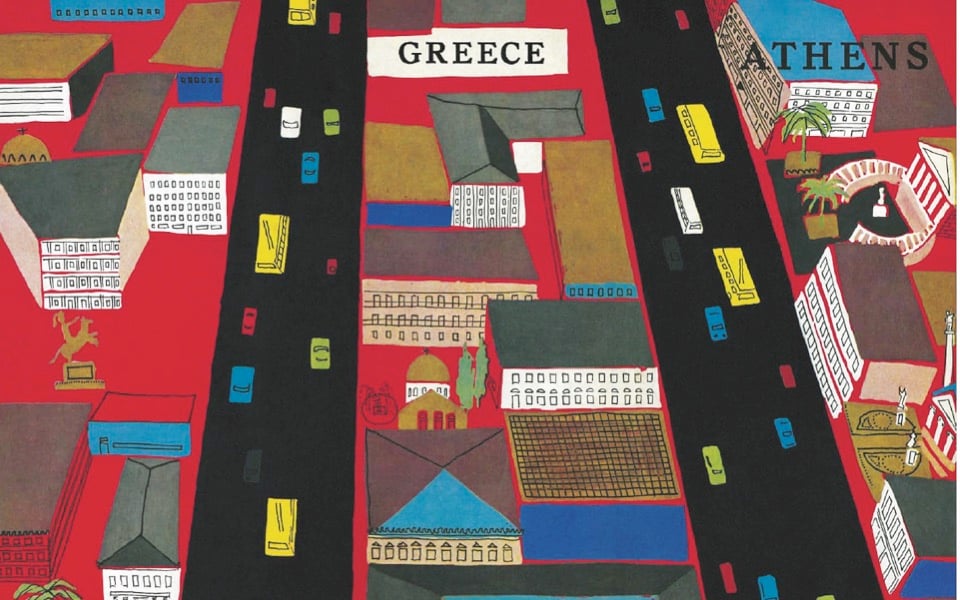

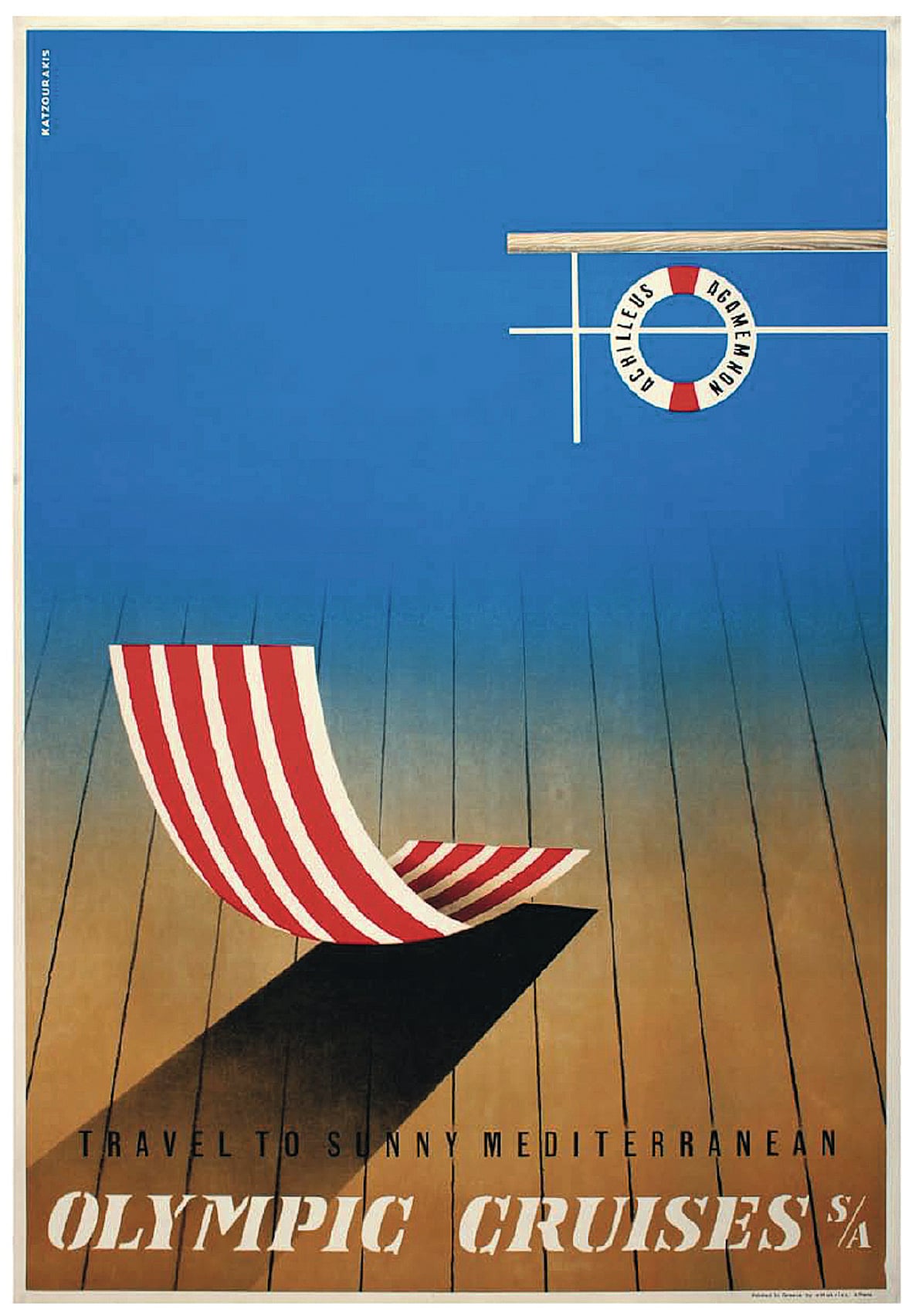

Tourist brochure for the Greek National Tourist Organization, 1960. Michalis Katzourakis, together with his wife Agni and fellow prominent graphic designer Freddie Carabott, redefined the concept of visual communication in Greece.

Michalis Katzourakis passed away at the age of 92, on Christmas Eve, in 2025. The prominent graphic designer, painter and sculptor, bookended an era when aesthetics was a way of life and the image of Greece a matter of morality. Collaborating with a small group of visionaries, and always having his life partner, Agni, at his side, he redefined the image of Greece, imbuing tradition with European modernism.

The thread of his life began on January 28, 1933, in Alexandria, Egypt. His birth at this historical crossroad endowed him from the very beginning with the cosmopolitan aura and the broadness of spirit that characterized the great Mediterranean metropolis, the memory of which was inscribed in him mainly as a sense of light and as a photographic memory. The family decided to move to Athens, and specifically to the suburb of Psychiko, in 1938.

The thread of his life began on January 28, 1933, in Alexandria, Egypt. His birth at this historical crossroad endowed him from the very beginning with the cosmopolitan aura and the broadness of spirit that characterized the great Mediterranean metropolis, the memory of which was inscribed in him mainly as a sense of light and as a photographic memory. The family decided to move to Athens, and specifically to the suburb of Psychiko, in 1938.

A decisive factor in his artistic awakening was his proximity to the sculptor George Zongolopoulos. At the age of just 11, Katzourakis found himself observing the artist in his studio, which was located down the street from his parental home. This space served as a refuge and his first real school, with Zongolopoulos taking on the role of mentor, supporting the teenager’s dreams against his father’s concern about the financial insecurity of artistic professions. Within that workshop, he experimented with materials and forms, cultivating a sculptural perception that would later permeate all of his work.

A flaneur in Paris

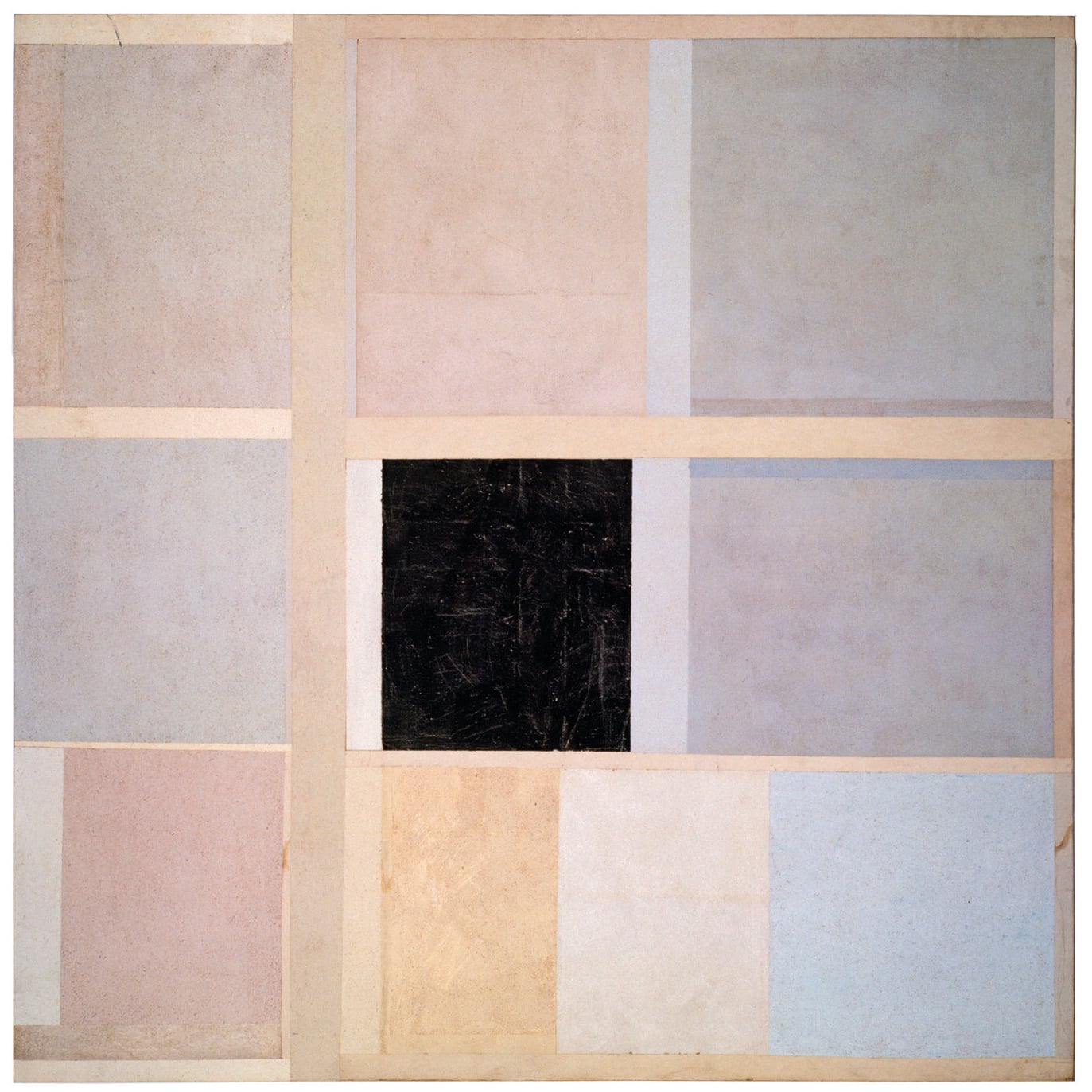

The search for his personal identity led him to Paris and to the school of the great illustrator Paul Colin. There he was introduced to the concept of the “flaneur,” the walker who discovers the soul of the city through aimless wandering. According to curator Christoforos Marinos, the artist treated the city as an open laboratory, walking the streets and collecting traces scattered throughout the urban fabric, with the camera taking on the role of a “notebook” and the primary material from which the visual work would emerge. The fruit of this method was the emblematic chapter of “Partitions” a visual study on the “trauma” of the city, which Marinos describes as “ready-made painting.”

Katzourakis’ work has achieved the rarest privilege for a creator: It has been fully absorbed by the collective gaze, becoming an organic part of urban culture

Katzourakis was fascinated by the spectacle revealed by the demolition of an apartment building. With the collapse of the building, the wall of the adjacent building was left with an impressive imprint of the life that had existed before. Stairs leading into the void, traces of bathroom tiles, room colors and remnants of wallpaper accidentally sculpted an unintentional painting. He found on these surfaces an urban palimpsest of memory and matter. He then transferred this feeling to the workshop, creating variations of the same theme, preserving the aesthetics of the ruin.

‘Untitled,’ 1985.

‘Untitled,’ 1985.

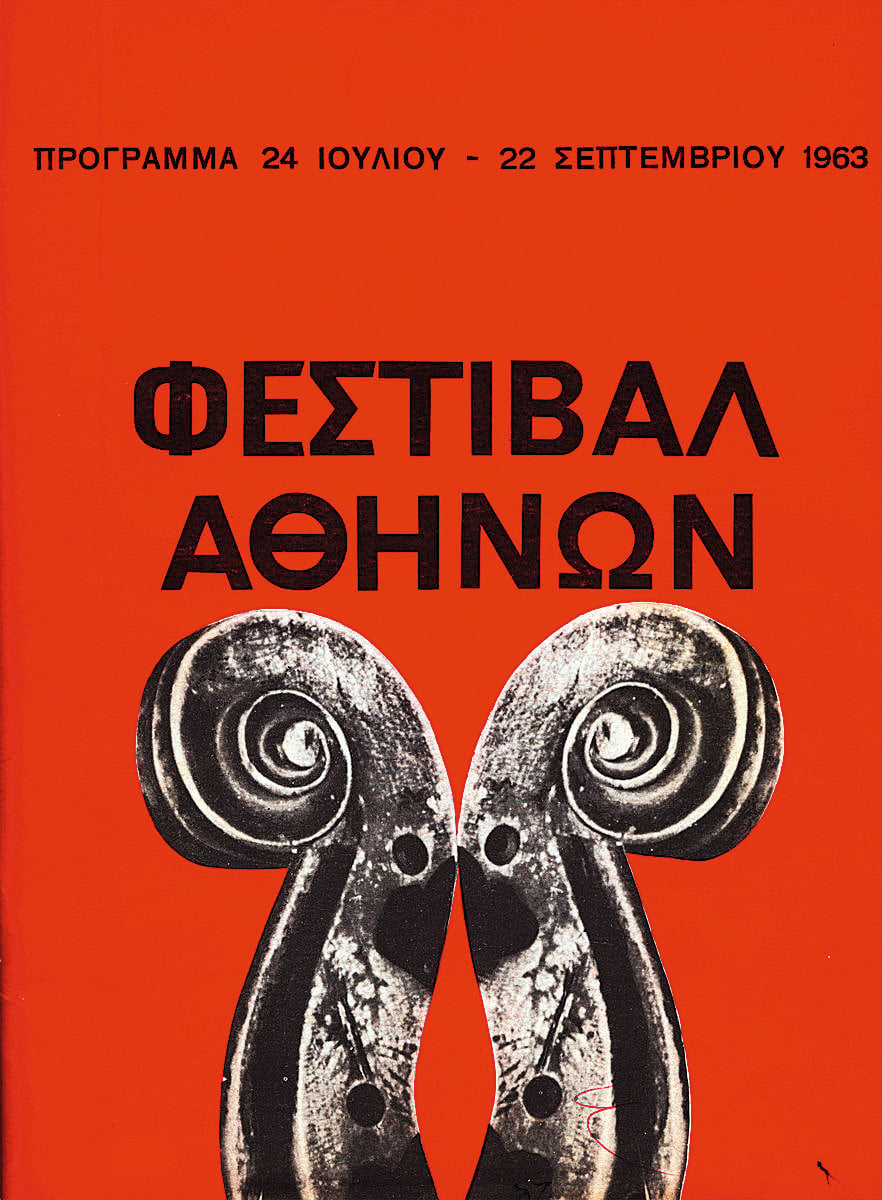

The return to Greece brought the most defining meeting in his life, his acquaintance with Agni, who became his companion and collaborator. They soon married and created a lifelong relationship based on mutual appreciation and a shared creative vision. Together they faced the challenges of the time and started working on their projects. The collaboration with the other giant of Greece’s post-war modern design, the inimitable Freddie Carabott, began on the occasion of an advertising campaign for herring, to evolve in 1962 into the founding of the legendary K&K-Athens Advertising Center. Katzourakis, Freddie and Agni redefined the concept of visual communication in Greece, claiming the artistic independence of the graphic arts and introducing minimalism and rationality into design.The Carabott-Katzourakis duo brought a cosmopolitan spirit, using their experiences abroad. Their worthy continuator, the great graphic designer Dimitris Arvanitis, analyzing this period in the catalogue “Design Routes” of their retrospective exhibition at the Benaki Museum in 2008, describes their work as the “spring of graphic design” in Greece.

Arvanitis observes that logical discourse, the absolute control of their tools and the strategic use of abstraction characterized the work of their pioneering creative office. In an environment that was searching for its unique view, the team introduced “clean design”: From the tourist posters of the Greek National Tourist Organization, which brought modernism to the countryside, to the internationally recognized logos that defined the country’s corporate identity, K&K identified with quality. Global recognition came in 1962, with a first prize in the International Tourist Poster Competition in Livorno, Italy. This triumph was crowned in 1968 with their entry into the Alliance Graphique Internationale (AGI), the strictly selective association that brings together the global elite of visual communication.

Arvanitis observes that logical discourse, the absolute control of their tools and the strategic use of abstraction characterized the work of their pioneering creative office. In an environment that was searching for its unique view, the team introduced “clean design”: From the tourist posters of the Greek National Tourist Organization, which brought modernism to the countryside, to the internationally recognized logos that defined the country’s corporate identity, K&K identified with quality. Global recognition came in 1962, with a first prize in the International Tourist Poster Competition in Livorno, Italy. This triumph was crowned in 1968 with their entry into the Alliance Graphique Internationale (AGI), the strictly selective association that brings together the global elite of visual communication.

The visual side

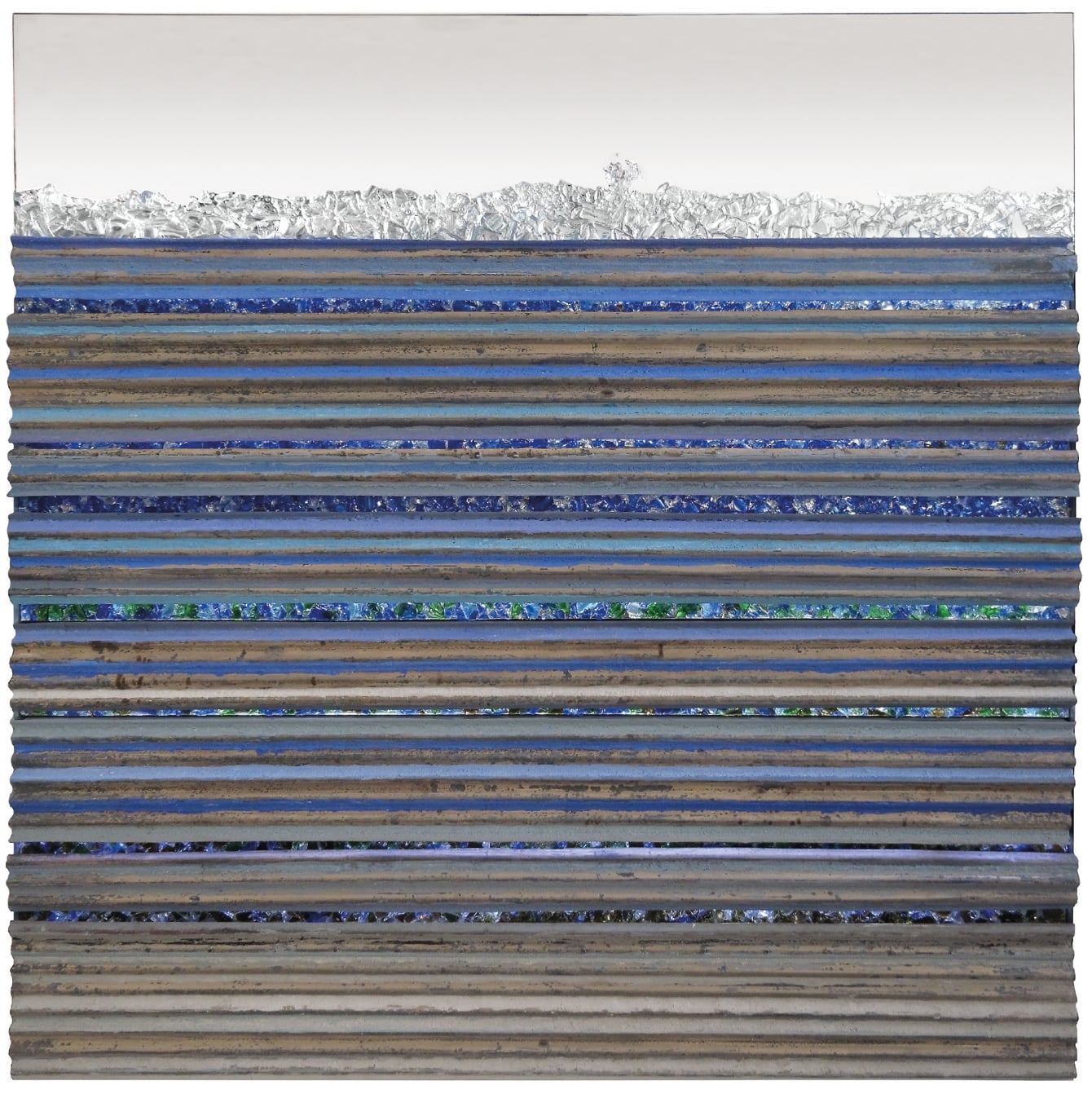

In parallel with applied art, Katzourakis developed a deep and autonomous path in pure visual creation. The exhibition at the Goethe Institute in 1969 was a real milestone for Greek visual arts, as he boldly introduced minimalist art to Athens. Abandoning traditional media, he presented three-dimensional constructions and environments made of industrial materials – such as plexiglass, neon and metal – creating spaces dominated by absolute geometry and light. While in Berlin, a passer-by asked him what an abstract sculpture of his represented, and he answered with disarming honesty: “It represents itself.” For him, a work of art was an autonomous object.

‘Aegean,’ 2016.

‘Aegean,’ 2016.

His involvement with interior design, especially those of cruise ships, was a field where his creative eye essentially met that of his spouse, Agni. Their collaboration with shipowner Pericles Panagopoulos for the Golden Odyssey in 1975 led to the creation of a floating work of art. A strict and functional color coding was applied to the decks, helping the passengers to orient themselves through the aesthetic experience.

‘Windows’ in the city

His constantly restless gaze, however, returned to the city and its silent spots. The series on “Windows” constitutes one of the most poetic and esoteric chapters of his work. He is enchanted by the sealed window, the closed, damaged, broken opening of an abandoned building in Kerameikos or the refugee housing (Prosfygika) on Alexandras Avenue. These silent elements tell a life story that has been completed. They are the imprint of human presence in the absence of man. He photographed and archived these elements with the consistency of a collector of moments during his travels around the world.

His work remains ubiquitous in public spaces, permeating every aspect of everyday life. From the monumental travel posters that re-established Greece in the world to the familiar logos that accompanied generations, and from his visual interventions in buildings to public sculptures, his imprint forms the backbone of our visual memory. Katzourakis’ work has achieved the rarest privilege for a creator: It has been fully absorbed by the collective gaze. His images are now an integral, organic part of urban culture, functioning as self-evident landmarks of a shared aesthetic experience, where creation transcends the artist’s signature and becomes the property of the collective consciousness. The essence of this invaluable heritage is always among us, confirming Arvanitis’ observation: It constitutes an “active part of our potential,” a “national heritage” which clearly proves that “simple is not easy.”

His work remains ubiquitous in public spaces, permeating every aspect of everyday life. From the monumental travel posters that re-established Greece in the world to the familiar logos that accompanied generations, and from his visual interventions in buildings to public sculptures, his imprint forms the backbone of our visual memory. Katzourakis’ work has achieved the rarest privilege for a creator: It has been fully absorbed by the collective gaze. His images are now an integral, organic part of urban culture, functioning as self-evident landmarks of a shared aesthetic experience, where creation transcends the artist’s signature and becomes the property of the collective consciousness. The essence of this invaluable heritage is always among us, confirming Arvanitis’ observation: It constitutes an “active part of our potential,” a “national heritage” which clearly proves that “simple is not easy.”