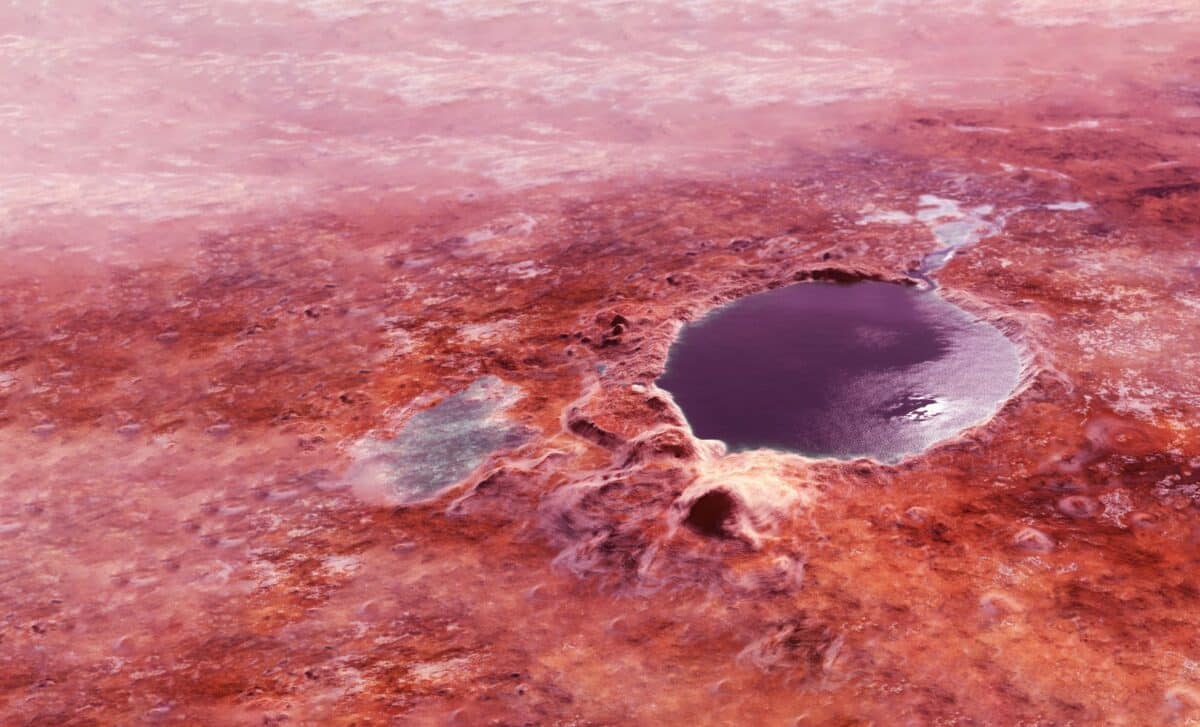

A new climate model suggests that ancient lakes on Mars may have survived for decades beneath thin layers of ice that formed and melted with the seasons. The findings help resolve a long-standing contradiction between geological evidence of water and models predicting a frozen planet.

The study, led by Eleanor Moreland of Rice University, presents a solution rooted not in warmth, but in insulation. Rather than demanding Earth-like temperatures, the research proposes that lakes may have endured under thin, seasonal ice covers that protected them during cold spells and allowed them to remain liquid for extended periods.

Stable Lakes Despite a Freezing Climate

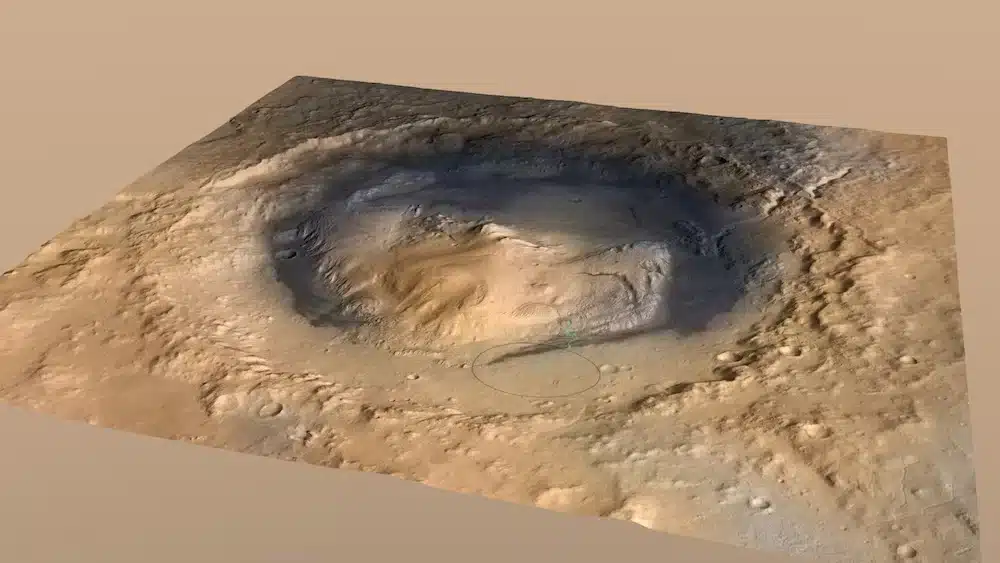

According to Earth.com, early Mars had a weak sun and a thin, carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere, conditions that should have kept the planet locked in ice. Yet NASA’s Curiosity rover and other missions have found multiple features pointing to standing water that lasted far longer than a single melt event. Minerals formed in lakes, as well as well-preserved sediments, suggest stability over time.

Eleanor Moreland, the study’s lead author, questioned how these lakes could have persisted.

“When our new model began showing lakes that could last for decades with only a thin, seasonally disappearing ice layer, it was exciting that we might finally have a physical mechanism that fits what we see on Mars today,” she stated in the report.

This ice wouldn’t have been thick like polar glaciers. Instead, it would form and melt rhythmically, season after season, slowing evaporation and heat loss just enough to allow water to linger. This could explain the absence of glacial erosion features in Martian lake beds while preserving their clean, undisturbed structure.

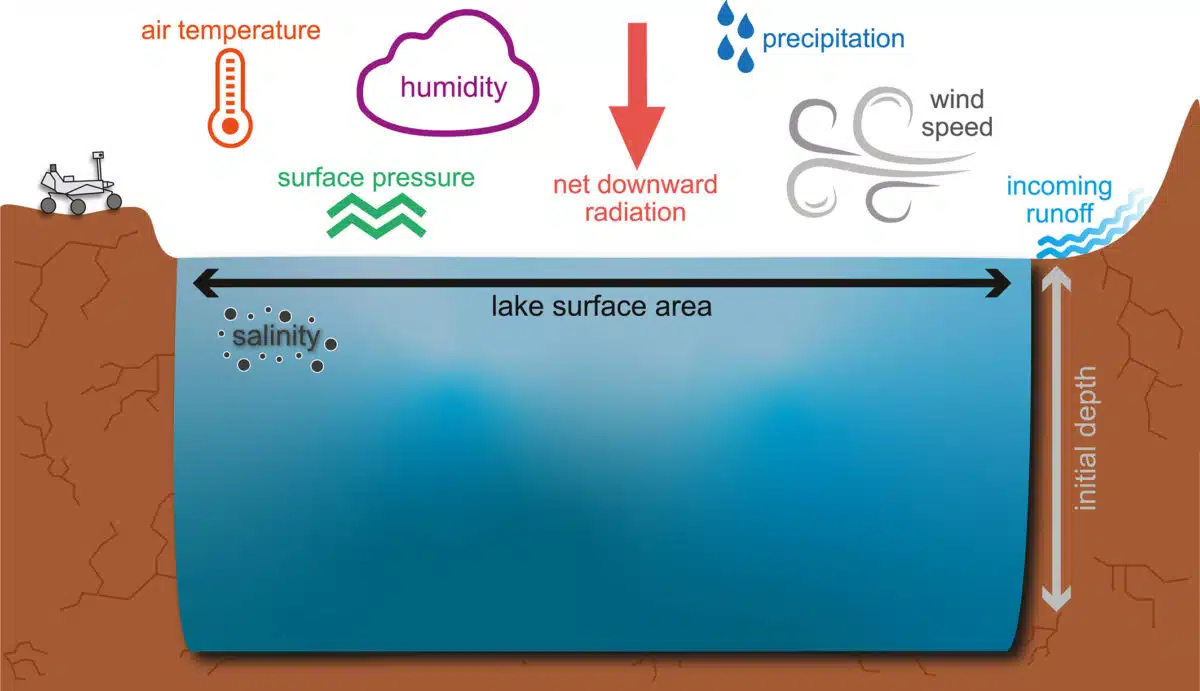

Structure of the LakeM2ARS model with annotated input parameters. Credit: Advancing Earth and Space Sciences

Structure of the LakeM2ARS model with annotated input parameters. Credit: Advancing Earth and Space Sciences

Earth-Based Model Adapted for Mars

The study’s research team, published in the journal Advancing Earth and Space Sciences, modified a tool originally developed to study Earth’s ancient climate: Proxy System Modeling. Since The Red Planet has no trees or ice cores to reconstruct its past, the team relied on data gathered from Martian rocks, minerals, and rover observations. They spent years reconfiguring the system to match the physics of Mars 3.6 billion years ago.

High-resolution model of Gale Crater, where Curiosity explores Mars’ sedimentary history. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESA/DLR/FU Berlin/MSSS.

High-resolution model of Gale Crater, where Curiosity explores Mars’ sedimentary history. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESA/DLR/FU Berlin/MSSS.

This led to the creation of LakeM2ARS (Lake Modeling on Mars with Atmospheric Reconstructions and Simulations), a Martian lake model that ran 64 simulations, each covering 30 Martian years (roughly 56 Earth years). Some modeled lakes froze solid and dried up. Others, under slightly different climate conditions, developed and retained seasonal ice that melted predictably.

Study co-author Professor Sylvia Dee explained that the model’s responsiveness to factors like atmospheric pressure and temperature fluctuations was key.

“It shows that with some creativity and experimentation, Earth-origin models can yield realistic climate scenarios for Mars,” she said.

Why Mars Had Lakes

The behavior of the thin ice proved central to the study’s success. Rather than erasing signs of water, the ice acted as a protective layer that would have left little geological trace. Professor Kirsten Siebach, another co-author, noted:

“Because the ice is thin and temporary, it would leave little evidence behind, which could explain why rovers have not found clear signs of perennial ice or glaciers on Mars.”

The preservation of shorelines, sediment layers, and lake basin shapes aligns with the idea of water shielded under seasonal ice. This mechanism doesn’t require the planet to have ever experienced warm, stable climates like Earth’s, only intermittent conditions that allowed surface water to endure longer than previously thought.

The team now plans to apply their LakeM2ARS model to other regions of Mars. If similar results emerge, it could reshape how scientists interpret the planet’s watery past and where they might search next for signs of ancient habitability.