For Mikel Arteta, it will be difficult to imagine life at Arsenal without Per Mertesacker.

The pair began their journey at the club together in the summer of 2011. It was in a hotel in Dortmund, Germany, that they both performed their initiation songs — Arteta giving his rendition of the Macarena, before Mertesacker launched into DJ Otzi’s Hey Baby, clutching a bread roll in place of a microphone.

In the seasons that followed, they reshaped Arsenal’s dressing-room culture and helped the club end a nine-year wait for silverware in the 2013-14 FA Cup. After retirement as players, Mertesacker and Arteta were recruited to lead the academy and first team, respectively.

Now, after almost 15 years with Arsenal — the past eight as academy manager — Mertesacker has announced his intention to step down at the end of this season.

“We were team-mates, we were friends, we were captains together, and then we shared this incredible project together in a different role — him as an academy director, and me as a manager,” Arteta told a press conference on Tuesday. “I’ve enjoyed every minute of it.

“He’s someone that transmits the values of this football club, its ambition, and everything that is related to it in the best manner.

“We’re very thankful.”

News of Mertesacker’s decision to step down was not entirely surprising to insiders at Arsenal. There has been a feeling over recent months that a change could be in the offing. For this article, The Athletic have spoken to sources close to the situation, who remain anonymous to protect relationships.

To an extent, Mertesacker’s exit is just part of the natural churn in any football club. Eight years in one role is some stint — 15 years at a single club, factoring in the final seven seasons of his player career, a distinguished feat in modern football.

Having started his post-playing days in such a senior position, there was also no obvious pathway for the German to progress at Arsenal.

Last year, he was not considered as a candidate for either the sporting director or technical director roles, which went to Andrea Berta and James Ellis, respectively. The implementation of a technical-director model also altered the club’s reporting structure in a way which impacted Mertesacker.

For their part, Arsenal have also been contemplating injecting fresh ideas into the academy leadership.

In an era of financial regulation, the need for a successful academy is greater than ever.

Their previous sporting director, Edu, recognised the importance of the academy, and was contemplating potential ways to raise its level before his sudden exit in November 2024. Since his departure, Arsenal have conducted a further review of academy operations, which has identified areas for potential improvements. Mertesacker was on a good salary, which restricted Arsenal’s ability to bring in additional expertise.

The 41-year-old’s decision to step down is somewhat timely, then: it provides Arsenal with an opportunity to evolve. The club are grateful for Mertesacker’s work, and recognise he is going to be a tough act to follow. They will take their time to identify an appropriate replacement.

He will leave behind an academy shaped around his values.

It was Ivan Gazidis, chief executive from 2009 until 2018, who initially appointed Mertesacker, encouraged by then first-team manager Arsene Wenger — and a certain influential team-mate. When Arteta retired from playing at the end of the 2015-16 season, he urged Arsenal’s leadership to retain Mertesacker in some capacity, recognising the value the 2014 World Cup winner could continue to provide in his thirties.

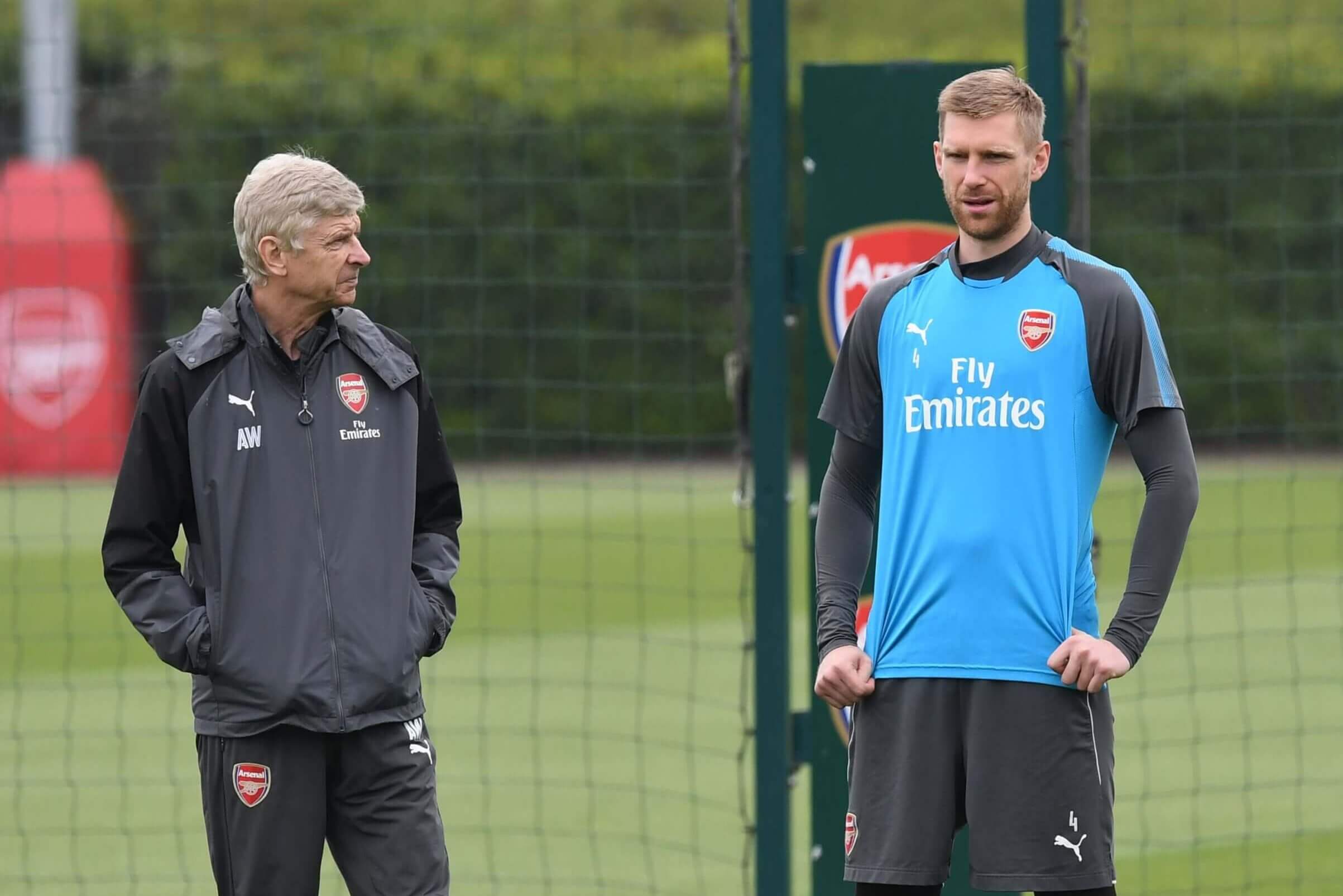

Mertesacker pictured with Wenger in 2018 (Stuart MacFarlane/Arsenal FC via Getty Images)

Mertesacker was partly appointed, following his retirement three years later, to provide the academy with a figurehead — a celebrated former player whose profile would help persuade youngsters that Arsenal were the club for them and charm their families.

This was far more than a mere ambassadorial role, however: Mertesacker had to learn on the job and get to grips with every aspect of running the academy. He was thrown in at the deep end — but this 6ft 6in (198cm) international-cap centurion was more than capable of handling that. He has thrown himself into everything: as well as his academy duties, Mertesacker also had a brief stint as first-team assistant coach during Freddie Ljungberg’s time as caretaker manager before Arteta’s December 2019 appointment.

An appraisal of Mertesacker’s stewardship of the Arsenal academy brings into focus a crucial question: what is an academy for?

If the answer is “producing first-team talent”, then his tenure must be considered an unqualified success. The first-team squad can today call upon audaciously talented academy graduates such as Bukayo Saka, Ethan Nwaneri, Myles Lewis-Skelly, Max Dowman and Marli Salmon. These players are the pride of the Hale End operation — and have arguably saved the club hundreds of millions in transfer fees.

But at a time when intense competition and financial rules mean Arsenal are obliged to squeeze every possible revenue source, an academy must also generate tangible income. The sales of players such as Joe Willock, Folarin Balogun, Emile Smith Rowe and Eddie Nketiah have attracted eye-catching fees, but there is still a feeling that Arsenal could do more in this area.

The club have cast envious eyes at the manner in which the likes of Chelsea and Manchester City have turned their youth programme into a consistent flow of cash. This requires careful management of career pathways, including arranging appropriate loan moves. Arsenal will target this as somewhere they can improve.

It also requires aggressive and ambitious recruitment of academy talent to start with. At Arsenal, the first team have naturally been the focus of investment — Mertesacker has not always had the funds at his disposal to compete with rivals such as Chelsea.

Lewis-Skelly, left, and Nwaneri are two of the recent academy graduates to reach Arsenal’s first team (Stuart MacFarlane/Arsenal FC via Getty Images)

There is, of course, a third function of an academy: providing young people with a foundation that sets them up well for the future — be that in the first team at the club concerned, elsewhere in wider football, or simply in life in general.

It is here that Mertesacker’s influence has been most keenly felt.

He has led Arsenal’s efforts to create ‘Strong Young Gunners’ who excel on and off the pitch. He has championed Arsenal’s core belief that better people make for better players, emphasising the key traits of respect, humility and discipline.

The likes of Saka embody those values. Those now first-team players will be the German’s legacy — as will the countless others who go out into the world from Arsenal’s academy, carrying his message with them.

After going straight into an administrative role after retirement from playing, nobody would begrudge Mertesacker a break from the game. His days as a player, he was with hometown club Hannover and Werder Bremen before coming to north London, mean he is already a wealthy man.

Sources suggest, however, that he is keen to find a new post soon, with potential opportunities back in Germany. Mertesacker has previously been courted by the national football federation. After these 15 years in London, perhaps a return home beckons.

Mertesacker’s departure will mean another former Arsenal player leaving the building for jobs elsewhere, relatively soon after the exits of Edu and Jack Wilshere. Arteta now stands alone as a prominent ex-player in the organisation. While none of these men were hired by Arsenal purely for their club association, the trend may be an indication of progress: the club have built a strong enough culture that they’re now able to look forward, rather than back.

The fact that Mertesacker will stay until the end of the season indicates how positive the relationships remain.

Setting his professional accomplishments aside, it is his human qualities that will be most missed. He remains an unfailingly affable, thoughtful and dignified presence at the club’s London Colney base.

Good people make better players. Turns out they make for good academy managers, too.