In a new study published in The Planetary Science Journal, scientists from the University of Chicago and Jet Propulsion Laboratory have uncovered unexpected findings about Jupiter’s atmosphere. The study reveals that the gas giant holds roughly 1.5 times more oxygen than our Sun, a crucial detail that reshapes our understanding of Jupiter’s formation and its chemical makeup. This new information is part of the most comprehensive atmospheric model of Jupiter to date, providing deeper insight into the complex chemistry of the planet.

The Importance of Oxygen on Jupiter

Oxygen is one of the most abundant elements in the universe, and its presence on Jupiter has been a topic of debate among planetary scientists for years. For decades, studies have disagreed on how much oxygen Jupiter contains, with some recent studies even suggesting it was much less than the Sun. However, the new model developed by researchers at the University of Chicago proposes that Jupiter holds about 1.5 times more oxygen than the Sun, significantly reshaping our understanding of the planet’s composition.

“This is a long-standing debate in planetary studies,” said Jeehyun Yang, a postdoctoral researcher at UChicago and the first author of the study, published in The Planetary Science Journal, The precise quantity of oxygen is more than just a scientific curiosity, it offers important clues about how Jupiter formed and how the solar system as a whole evolved. Oxygen is a key element in the formation of water, and understanding its presence and distribution could also help researchers learn more about the conditions that allow for the formation of habitable planets beyond our solar system.

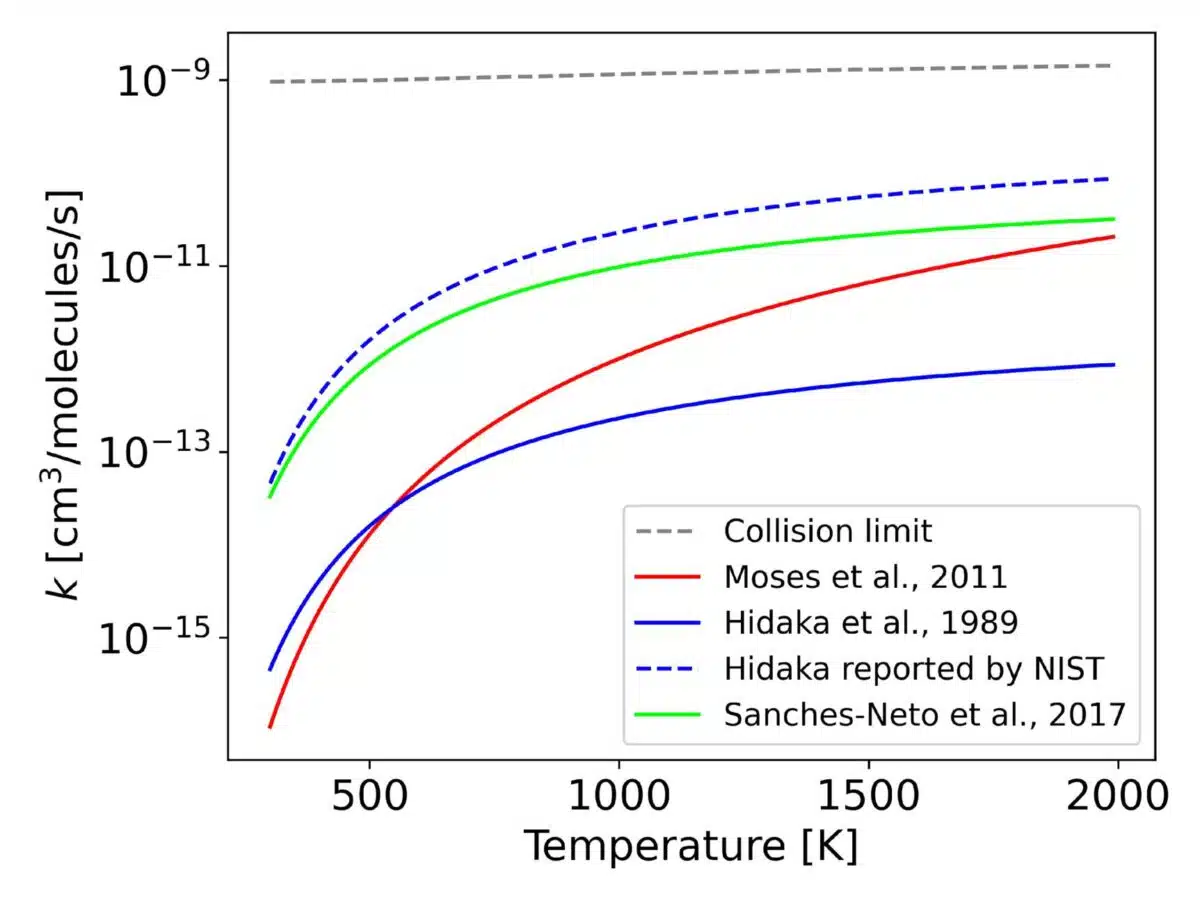

The temperature dependence of the rate coefficients for the reaction CH3OH + H→CH3 + H2O from various references. The solid blue line represents the original rate coefficient reported by Y. Hidaka et al. (1989), the blue dashed line corresponds to an incorrect version of this rate listed in the NIST database (J. Manion et al. 2020), the red solid line shows the rate coefficient calculated by J. I. Moses et al. (2011), the lime solid line represents the rate calculated by F. O. Sanches-Neto et al. (2017) using the d-TST method, and the gray dotted line shows the collision limit calculated using Equation (1) from D. Chen et al. (2017) for reference.

The temperature dependence of the rate coefficients for the reaction CH3OH + H→CH3 + H2O from various references. The solid blue line represents the original rate coefficient reported by Y. Hidaka et al. (1989), the blue dashed line corresponds to an incorrect version of this rate listed in the NIST database (J. Manion et al. 2020), the red solid line shows the rate coefficient calculated by J. I. Moses et al. (2011), the lime solid line represents the rate calculated by F. O. Sanches-Neto et al. (2017) using the d-TST method, and the gray dotted line shows the collision limit calculated using Equation (1) from D. Chen et al. (2017) for reference.

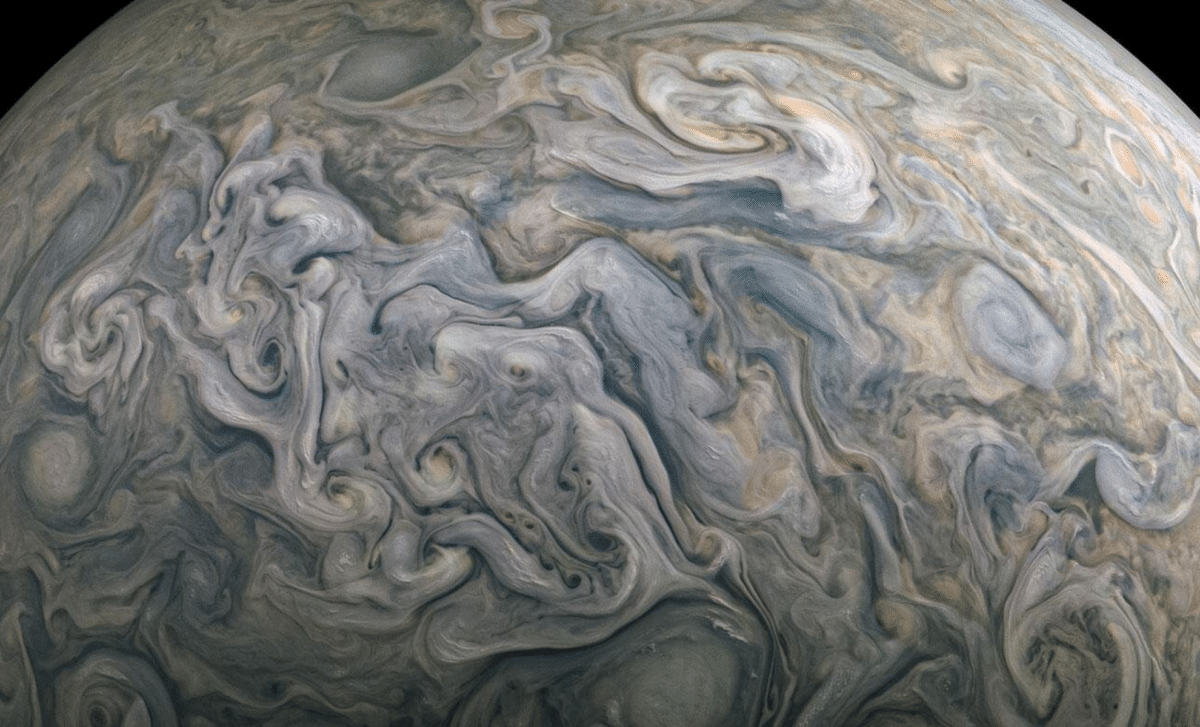

Jupiter’s Atmosphere: A Complex and Dynamic System

Jupiter’s atmosphere is notoriously difficult to study due to the thick clouds that cover the planet’s surface. The Great Red Spot, a massive storm twice the size of Earth, and other violent weather patterns have kept scientists from getting a clear view of what lies beneath. Previous missions, such as NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, were unable to make measurements deep within the planet’s atmosphere. However, recent measurements from the Juno spacecraft, which orbits Jupiter, have provided valuable data on the composition of the upper layers of the atmosphere, including ammonia, methane, and carbon monoxide.

Despite these advances, scientists have struggled to build a model that accurately reflects the complex interactions between the planet’s chemistry and hydrodynamics. Traditional models have been based on simpler assumptions about the behavior of gases and clouds, often overlooking how water droplets and cloud formations impact chemical reactions. As Yang explains,

“You need both [chemistry and hydrodynamics]. Chemistry is important but doesn’t include water droplets or cloud behavior. Hydrodynamics alone simplifies chemistry too much. So, it’s important to bring them together.”

The new model integrates both these aspects, allowing for a more accurate representation of the planet’s atmosphere. This has allowed the researchers to make better predictions about the oxygen content on Jupiter, as well as the slow, complex circulation patterns that govern the planet’s atmosphere.

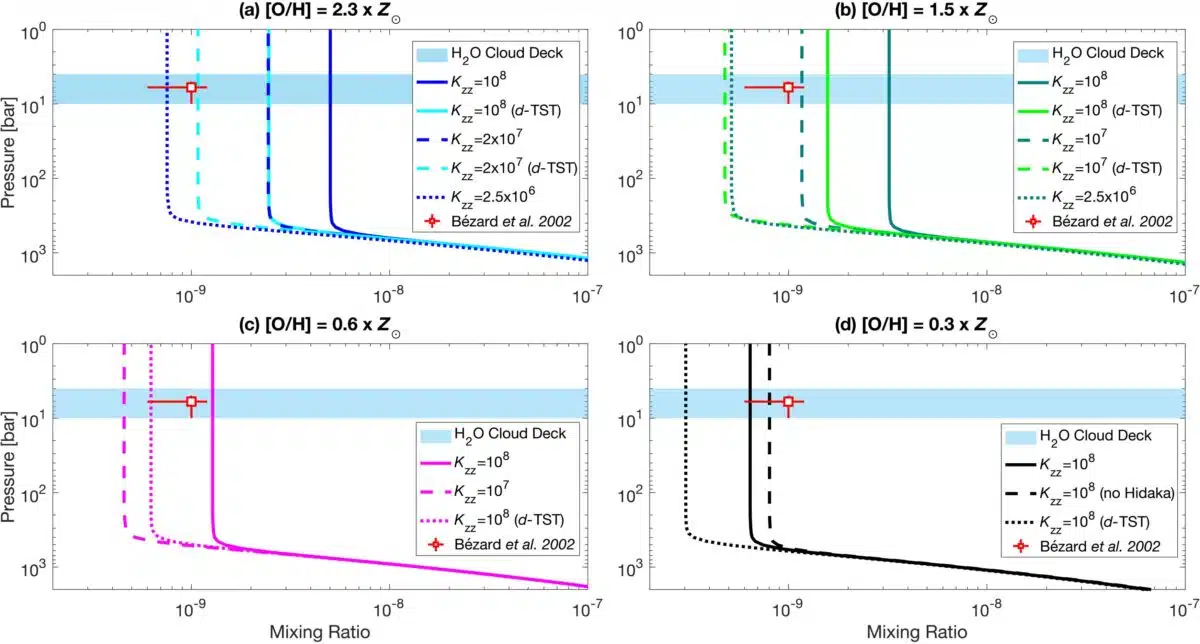

Vertical mixing ratio profiles of carbon monoxide ([CO]/[H2]) in Jupiter’s atmosphere for various oxygen abundances O/H (Section 2.1): (a) 2.3 Z⊙, (b) 1.5 Z⊙, (c) 0.6 Z⊙, and (d) 0.3 Z⊙. In each panel, we vary the eddy diffusion coefficient Kzz [cm2 s–1] and adopt the Hidaka reaction rate coefficient from either J. I. Moses et al. (2011; nominal) or F. O. Sanches-Neto et al. (2017; indicated as d-TST). Panel (d) additionally shows the CO profile simulated with the Hidaka reaction omitted from the chemical network described in Section 2.3. The red square with error bars indicates the observed upper-tropospheric CO mixing ratio from B. Bézard et al. (2002), with uncertainties from G. L. Bjoraker et al. (2018). The light-blue shaded region indicates the water cloud decks between 4 and 10 bars.

Vertical mixing ratio profiles of carbon monoxide ([CO]/[H2]) in Jupiter’s atmosphere for various oxygen abundances O/H (Section 2.1): (a) 2.3 Z⊙, (b) 1.5 Z⊙, (c) 0.6 Z⊙, and (d) 0.3 Z⊙. In each panel, we vary the eddy diffusion coefficient Kzz [cm2 s–1] and adopt the Hidaka reaction rate coefficient from either J. I. Moses et al. (2011; nominal) or F. O. Sanches-Neto et al. (2017; indicated as d-TST). Panel (d) additionally shows the CO profile simulated with the Hidaka reaction omitted from the chemical network described in Section 2.3. The red square with error bars indicates the observed upper-tropospheric CO mixing ratio from B. Bézard et al. (2002), with uncertainties from G. L. Bjoraker et al. (2018). The light-blue shaded region indicates the water cloud decks between 4 and 10 bars.

Slower Diffusion Than Expected: A Key Discovery

One of the most striking discoveries from this study is the revelation that the movement of gases within Jupiter’s atmosphere is far slower than previously believed. According to the new model, the diffusion of molecules through the atmosphere is 35 to 40 times slower than the standard assumption. “Our model suggests the diffusion would have to be 35 to 40 times slower compared to what the standard assumption has been,” Yang said. “For example, it would take a single molecule several weeks to move through one layer of the atmosphere, rather than hours.”

This slower diffusion could have significant implications for how heat and chemical elements are transported within the planet. It may also affect the way clouds form and dissipate, influencing Jupiter’s weather patterns and storm dynamics. The discovery of this slow molecular movement adds another layer of complexity to the study of Jupiter’s atmosphere and challenges long-standing assumptions about how gases behave under extreme conditions.