China’s economic policymaking relies heavily on annual GDP growth targets, which are set by the central government and then filter down through China’s five-tiered bureaucracy (central government, provinces, prefecture-level cities, counties, and townships). The central government announces a national target each March. Provinces then set their own targets, typically above the national one, and cities set targets often above their provincial targets. This upward-ratcheting structure reflects political pressure embedded in China’s personnel evaluation system in which local officials are assessed in part on their ability to meet or exceed GDP growth targets. GDP growth targets are therefore not just planning tools, but also mechanisms of coordination, accountability, and political pressure across China’s administrative hierarchy. How do China’s annual GDP growth targets shape local government investment decisions, land sales, and accumulation of debt, and how does this affect the disconnect between headline GDP and underlying economic fundamentals?

The data. The paper combines two decades of national, provincial, and city-level economic data to quantify how local governments respond to growth target pressure. To measure this pressure, the authors construct a “GDP gap,” defined as the difference between a region’s reported growth rate and its announced target. They link these gaps with provincial infrastructure investment, and with city-level land sales and local government debt (official bond issuance and local government financing vehicles). To assess broader economic consequences, the authors correlate provincial GDP with firm-level revenue growth, retail sales growth, and city-level total factor productivity (TFP). Together, these data allow the researchers to isolate how deviations from growth targets systematically shape local economic behavior.

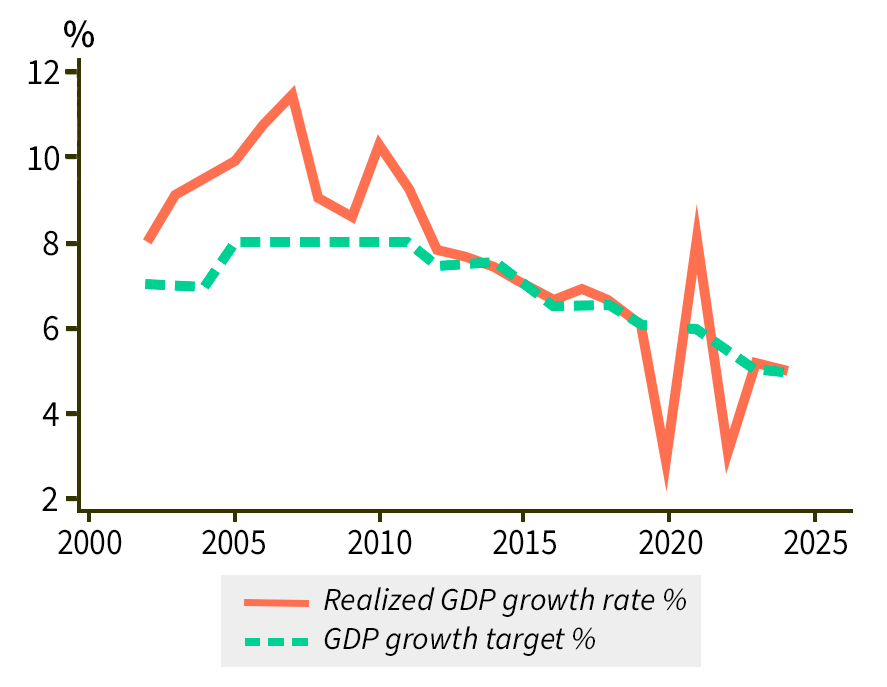

Annual growth targets and realized growth rates

China’s slower growth turned GDP targets into obligations. In the 2000s, China’s economy grew so quickly that national GDP targets were largely symbolic: the central government set goals of about 7% to 8%, while actual growth easily exceeded them, often by more than 2 percentage points. After 2010, as growth slowed, the gap between targets and outcomes narrowed sharply. From 2011 to 2019, realized growth stayed within about 0.5 percentage points of the target almost every year. This unusually tight alignment, especially for an economy of China’s size, indicates that the need to hit growth targets increasingly shaped local policy choices.

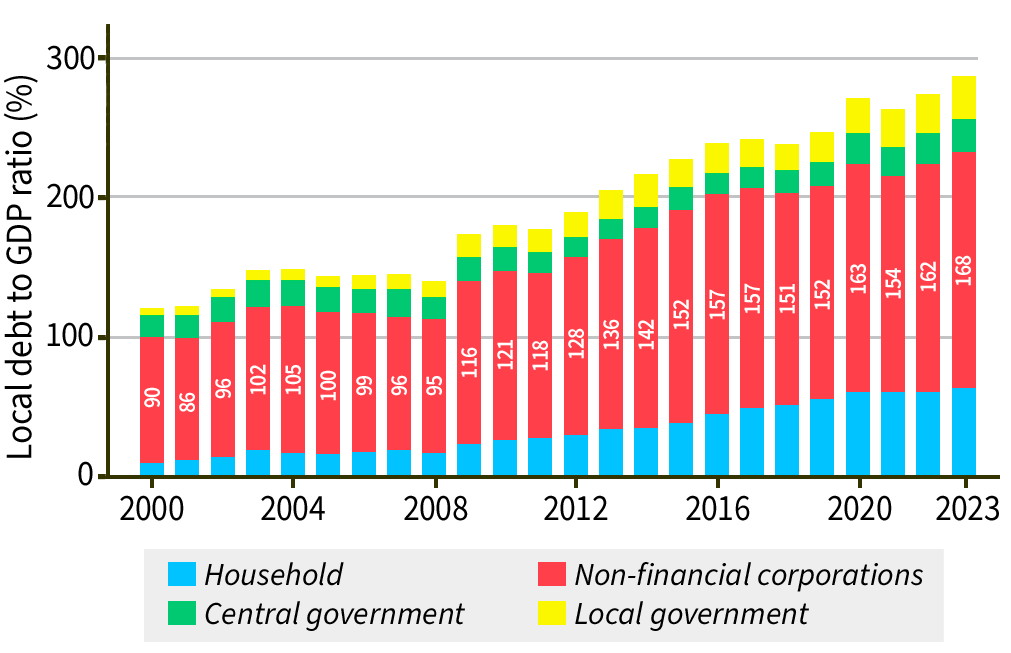

Closing the GDP gap with spending and debt. After 2010 the researchers find local governments began to respond directly to shortfalls between the target and their actual growth rate. When a province fell 1 percentage point short of its target, it increased infrastructure investment by about 0.4% of provincial GDP. At the city level, a 1 percentage point shortfall is associated with an increase in land sales worth about 0.07% of GDP, which helped generate the off-budget revenue needed to finance spending. Most strikingly, the same 1 percentage point shortfall is associated with a 0.76% of GDP increase in local government debt, including both official local bonds and borrowing by local government financing vehicles. The consistency of these patterns shows that local governments rely on a common playbook: spend more, sell more land, and borrow more whenever growth looks too weak to meet the target.

China’s infrastructure investment

Chasing targets inflated local debt. During the 2011 to 2019 period, China’s reported national growth rate appeared remarkably stable, but the analysis shows this stability came at a significant cost. City governments consistently set targets that were higher than what their economies could naturally achieve. Across the decade, the average city accumulated a total growth shortfall of 18.4 percentage points relative to its self-assigned targets. The authors calculate that these repeated shortfalls contributed the equivalent of about 14% of national GDP to local government debt. The result suggests that a large share of the rise in local debt during the 2010s was a direct outcome of the pressure to deliver stable headline growth in a slowing economy.

Hitting the target but missing the prosperity. In the early 2000s, provincial GDP growth was strongly correlated with the performance of real firms and households. From 2002 to 2008, a 1 percentage point increase in provincial GDP growth was associated with a large and statistically significant increase in the revenue growth of publicly listed firms, as well as meaningful gains in retail sales and city-level TFP. But during the 2011 to 2019 period, the correlation between provincial GDP growth and firm revenue growth fell close to zero. Retail sales growth no longer rose in tandem with higher GDP growth. City-level TFP, once tightly linked to GDP performance, showed almost no relationship with it during this later period.

When a metric becomes a target, it is no longer a good metric. Taken together, the findings suggest that China’s smooth headline growth over the past decade has come at the cost of rising local debt, weakening links between GDP and real economic activity, and reduced flexibility in local policymaking. Because overly ambitious targets triggered interventions financed by land sales and borrowing, the growth target system has contributed to the buildup of fiscal risks now challenging many provinces and cities.