After giving the order for Nicolás Maduro’s kidnapping, Donald Trump declared that the United States was now planning to ‘‘run’’ Venezuela. “It won’t cost us anything,” Trump said,

because the money coming out of the ground is very substantial . . . The oil companies are going to go in. They’re going to spend money. We’re going to take back the oil that, frankly, we should have taken back a long time ago. A lot of money is coming out of the ground.

In the past, when Washington claimed to act in the name of humanitarianism, democracy, or freedom, it was up to us—political economists—to reveal its ulterior motives, the material interests beneath the media spin. Now, as TJ Clark has written, political hypocrisy itself seems to be under threat. If imperial resource-grabbing is openly acknowledged, what is left for us to analyze?

Over the last week, much of the debate on the US attack has questioned whether oil is really the determinant factor. Some argue that Venezuela’s heavy crude is too expensive to extract, and that—given the current state of the market and the unlikelihood of price increases in the near future—this would be an irrational investment for US corporations. Others, meanwhile, note that about half of Venezuela’s oil reserves are not of the heavy kind found in the Orinoco Belt, and claim that in oil fields in the Maracaibo and Monagas basins there is still the potential for “quick wins” for big oil companies and oil-service firms.

Either way, there are many other plausible motives for the US aggression. It could be conceived as a resource grab not in a long-term strategic sense, but rather a one-off act of extortion to benefit specific actors in Trump’s elite coalition—plundering Venezuela to pay the spurious compensation claimed by ConocoPhillips and ExxonMobil, for example, or to benefit US refineries that specialize in heavy oil. One could also see it as a spectacle for a domestic audience: a demonstration of imperial strength to galvanize the MAGA base and the Latino right who have long pushed for US-sponsored regime change in Cuba and Venezuela.

All this may begin to clarify as the situation in Venezuela develops over the coming months. But for now, the question I want to raise is about the relationship between the military operation and the longstanding policy of containing China’s rise. Here we need to assess not only the immediate impact of the attack, but also the warning shot it sends across the entirety of Latin America. Alongside tariffs, foreign investment screening, and export controls, restoring the Monroe Doctrine could be interpreted as a new pillar of the anti-China strategy that has been pursued by Democrat and Republican administrations alike since the 2008 financial crisis. While Maduro’s abduction struck many as madness, we may nonetheless be able to glimpse the outlines of a method.

Before we turn to this hypothesis, though, a word on Venezuela itself. The goal of this column is not to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the Bolivarian governments. There are abundant reasons to argue that the hopes created by Hugo Chávez’s rise had long been dashed, and that the combined effects of Maduro’s choices and foreign sanctions were deeply tragic. But it goes without saying that the US assault will only worsen the crisis. The failed record of “regime change,” from Iraq to Afghanistan to Libya and beyond, is testament to this. The White House itself has spoken much more about extracting Venezuelan oil than about liberating Venezuelans, as if to concede that the fantasies of the Bush administration can no longer be sustained in 2026.

“Our Hemisphere”

Three days after the attack on Caracas, the US State Department tweeted a black-and-white photo of Trump with the caption “THIS IS OUR HEMISPHERE.” They are not in the business of nuance and subtlety. This was no surprise to those who had read the White House National Security Strategy released last November, with its mention of a “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine. The latter was, of course, put forward in 1823 as decolonization took hold of Latin America, and asserted that the intervention of foreign powers anywhere in the hemisphere was a threat to US security. Though it lacked enforcement until the end of the nineteenth century, from then on it was used to justify all manner of violent interventions: in Panama, in Cuba, in the countries that experienced CIA-backed military coups in the 1960s and 1970s …Venezuela was the target of botched attempts at regime change in 2002 and again in 2019.

Trump’s National Security Strategy claims that the Monroe Doctrine must now be revitalized “after years of neglect.” One of its stated aims is to discourage “mass migration to the United States.” Another is to kick China out of Latin America: “we want a Hemisphere that remains free of hostile foreign incursion or ownership of key assets, and that supports critical supply chains; and we want to ensure our continued access to key strategic locations.”

The Trump Corollary also stresses the need for collaboration between Washington and Latin American governments to combat so-called “narco-terrorists, cartels, and other transnational criminal organizations,” hence the trumped-up drug trafficking charges against Maduro. In recent years, right-wing governments in the region have increasingly placed criminal organizations on terrorist lists, making them legitimate targets for US intervention in line with the Barbados Convention. In Brazil, Bolsonaro’s eldest son has suggested that he would like to see the US bombing of boats in the Caribbean repeated off the coast of Rio de Janeiro. If future US military action is to retain a veneer of legality—even the very thinnest one—it will surely be justified on the basis of new narco-terrorism legislation.

China and Latin America

It is not a Trumpian fantasy to say that China, a “non-Hemispheric competitor,” has forged deep ties with Latin America over the last two decades. As China became the workshop of the world, dominating East Asia’s production networks, it came to rely on massive quantities of minerals, fuels and agricultural products. The result was an increase in the price of commodities—the so-called commodity super cycle—which reshaped the role of many global South countries in the international division of labor. South America, with its penchant for exporting primary goods, played a crucial part in this process.

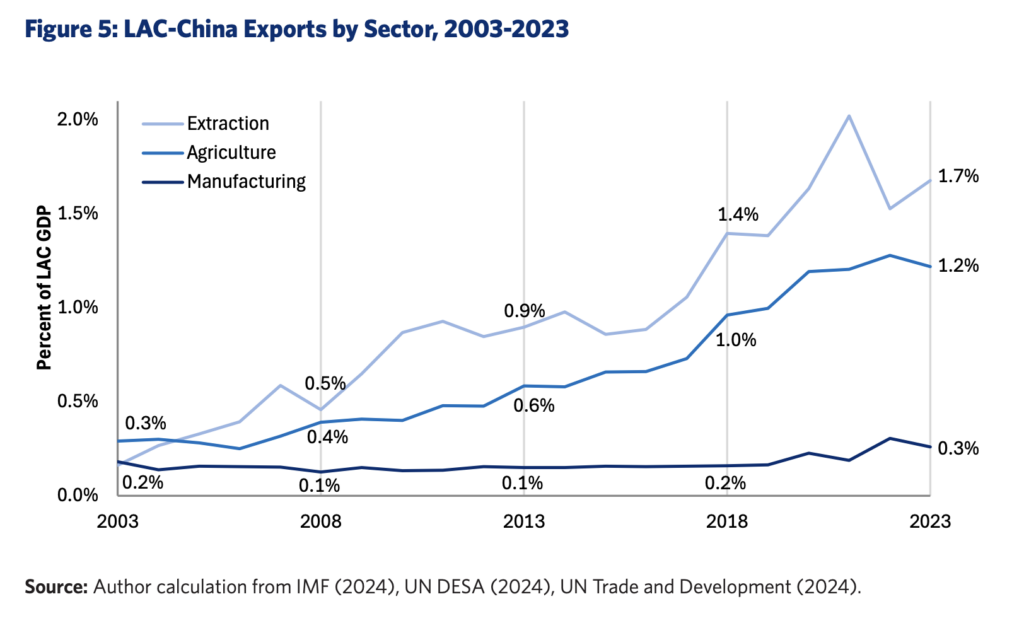

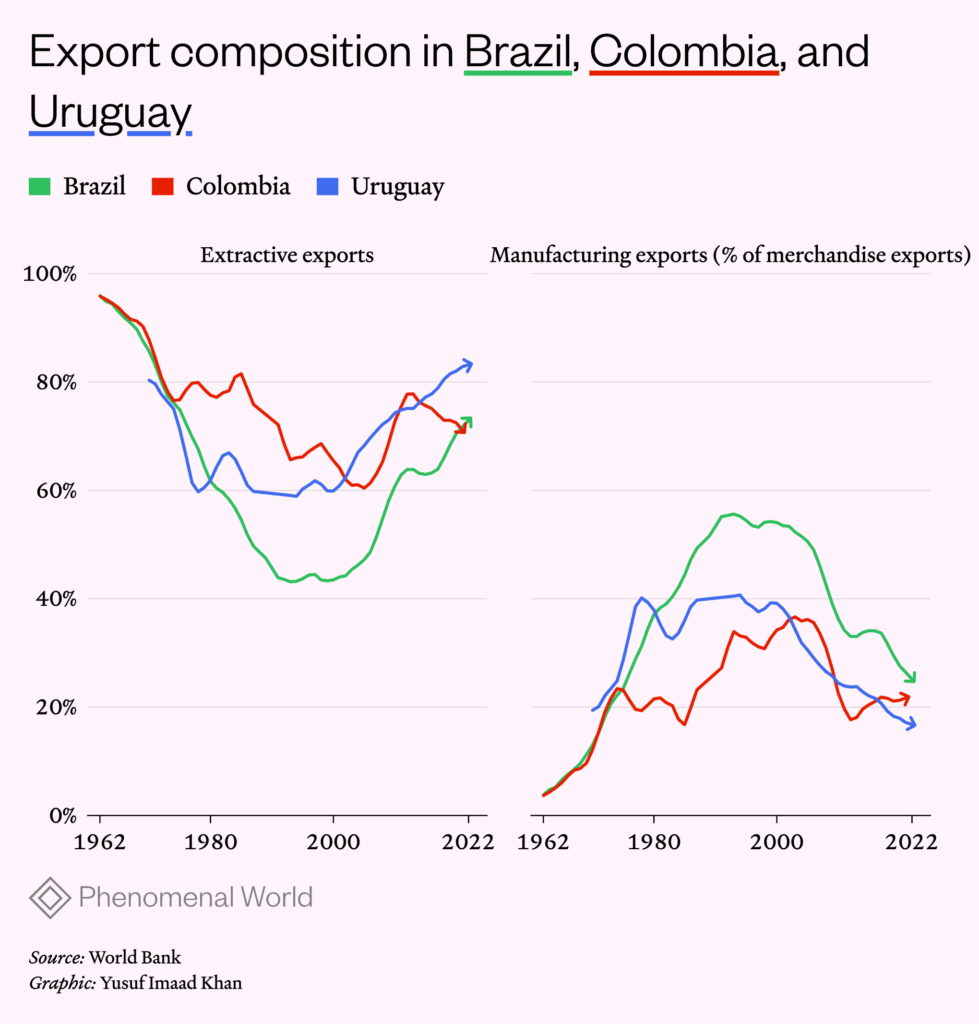

During this period, even the countries that had gone furthest in increasing the share of manufacturing goods in their exports quickly descended into extractivism. In the 2000s, on average, manufacturing exports accounted for 50 percent of total exports in Brazil, 35 in Colombia, and 32 in Uruguay. If we look at the averages for the 2010s, we see that these numbers had dropped to 33, 20 and 22 (Figure 1). This momentous shift can also be seen in the data on the destination of exports (Figure 2). For South America as a whole, the share of exports bound for China climbed from around 2 percent in the late 1990s to around a quarter since 2019, while the share going to the US dropped correspondingly. South America thus consolidated its role as a supplier of low value-added goods to Chinese production networks (Figure 3).

This dynamic comes into focus when we look at specific commodities. On average, 53 percent of the world’s exports of copper ore have come from South America since 2004. China imported just over 10 percent of the total in 2000, whereas in 2023 it accounted for 62 percent of all copper ore imports. The share of iron ore that South America exports has been declining in recent years but it remains the source of more than a fifth of the world’s total; since 2019, China imports more than two-thirds of all internationally traded iron ore. Minerals that are expected to play a major role in the development of renewable energy technologies—lithium, nickel, and rare earths—are also heavily concentrated in Latin America. As Helen Thompson has observed, “the attempted global energy revolution is starting to play out as a conflict between China and the US over metal resources in the Western Hemisphere.”

To return to oil, Latin America’s share is far from negligible (Figure 4). Its level of production in terms of barrels, when combined with that of Canada and the US, broadly matches that of the Middle East—and it may yet increase if Venezuelan oil infrastructure is reconstructed. At this point, one cannot guarantee the sidelining of oil by the energy transition; but even if that eventually happens, oil is likely to remain crucial for Washington’s military operations. As Javier Blas argues, by controlling the production in the Americas the US may be able to break the link between its wars abroad and its domestic fuel prices:

For decades, US military adventurism was constrained by the impact of any war on energy costs. Today the White House has primacy over oil-producing allies and adversaries alike—whether it’s Saudi Arabia or Iran, Nigeria or Russia. The past 18 months have already shown what these new hydrocarbon riches mean for US foreign policy. Trump’s administration has taken once unthinkable steps: from bombing Iranian nuclear facilities to helping Ukraine target Russian oil refineries. Grabbing Nicolas Maduro from his safehouse in the outskirts of Caracas was the most shocking example yet of what happens when oil doesn’t constrain the Pentagon anymore.

Figure 4

Amid the fallout of 2008, the China–Latin America connection moved beyond trade to finance and infrastructure, with a significant growth of Chinese direct investment in the region and the participation of Chinese firms in various construction projects. A prominent example is the Chancay mega-port in Peru, which is likely to further boost trade flows. A series of Latin American countries also opted to take out Chinese loans to avoid the conditionalities typically imposed by the World Bank or the IMF. Then, in 2018, China invited Latin America to join the Belt and Road Initiative, further entangling the region in its networks of international diplomacy and finance. Beijing’s relationship with Brazil, consolidated through a series of BRICS institutions, is part of this larger picture.

Doux Commerce

What motivates Chinese involvement in the region? China joined the WTO in 2001 and charted a development strategy that required it to integrate its economy into the circuitry of global capitalism: a decision that was welcomed by US foreign policy officials, who hoped it would set in motion an inexorable process of Chinese liberalization and subordination to the US-led global order. This assumption could be read as a remnant of the old doctrine of doux commerce, associated with Montesquieu, according to which commerce “polishes and softens barbarian ways.” US officials negotiating the WTO accession imposed extraordinarily stringent conditions, demanding that China “substantially open its markets in banking, insurance, securities, fund management and other financial services.”

The reordering of global capitalism that ensued was acceptable to the US largely because of the dynamics of debt-led consumerism. By 2001, the US economy had already gone through more than a decade of deindustrialization, with manufacturing production moving to Asia. Combined with the weakening of trade unions, the effect was to entrench stagnant wages. To make this compatible with what David Harvey called the “golden rule of never-ending consumerism,” finance had to be mobilized: with the exception of those at the very bottom of the income pyramid, most US households were able, for a time, to keep improving living standards with the aid of debt. The flow of cheap manufacturing goods from China helped by keeping inflation low.

This lasted until 2008, when the financial crisis exposed the unsustainability of workers’ indebtedness. From then on, those in precarious employment—living in impoverished towns across the US rustbelts and struggling to pay their debts—began to feel the cost of the restructuring of the global division of labor. The worsening economic situation was soon followed by epidemics of suicide and fatal overdoses, especially among non-college educated men: one of the main losers in the game of “globalization.” The stage was set for the rise of Trump. Careful empirical investigations by David Autor and his co-authors show that the localities most affected by the “China shock” played a decisive role in this political shift.

With Trump’s rise to the presidency in 2016, the cult of free trade was replaced by the trade and technology war with China. This was not an ephemeral change. The Biden administration intensified such trade measures and made them a cornerstone of what it called its “foreign policy for the middle class.” Two further events consolidated this transition. The first was Covid, which disorganized supply chains and pushed policy discussion towards the need for greater national resilience. The second was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, particularly its effects on European energy markets. At this point, even the most committed defenders of laissez faire took heed. The Economist argued in 2022 that “Russia’s war shows that supply chains need redesigning to prevent autocratic countries from bullying liberal ones.” There was a tension, as they put it, between free trade and freedom. Disillusion with doux commerce was widespread.

A pillar of Washington’s foreign policy over the past decade has been the export ban on US technology to China, prohibiting US firms from doing business with numerous Chinese counterparts and clamping down on the sale of particular high-tech goods. (Seans Starrs and Julian Germann offered a detailed description of these measures.) The recent negotiations on Nvidia chips are the latest iteration of this process that began with the Export Control Reform Act in 2018. Yet this approach is now running into a problem: once you compromise China’s production capacities in an attempt to stall its ascent, you need to find alternative sources of imported goods. This is where the redesign of supply chains, and all the talk about re-shoring and friendshoring, comes in. But among the many obstacles to this reorganization is the fact that most of the world’s natural resources are being sold to and refined by China. That, in turn, brings us back to Latin America and the US’s interest in controlling its resources.

Fragile Hegemon?

Following the attack on Caracas it seems that the US is keen to carry out its next performance of hard power, turning its attention to Greenland and perhaps Iran. Whether or not Trump follows through on his plan to “run” the country, though, I think the broader geopolitical context indicates that the logic of imperial rivalry is critically important here. Hypocrisy is on its way out; naked resource imperialism seems to be back in. Venezuela was first in the crosshairs; Colombia and Cuba may be next. Upcoming presidential elections in the region—Peru, Colombia, Brazil—could present Trump with new opportunities to assert hemispheric dominance, perhaps via the same methods of financial interference that he used in the Argentinian elections last year.

Whether the return of the Monroe Doctrine will help to reorder global supply chains, however, is another matter. The US is aware of its economic weaknesses—both in resources and in certain key technologies—and seems inclined to compensate by flexing its military might. Yet in the quarter century since China joined the WTO, profound interdependencies have developed between West and the East, and efforts to dismantle them could easily backfire. The volatility of Trump’s tariffs is partly a sign of this difficulty.

Nor are other actors simply going to stand still. Under increasing pressure, China is strengthening its control over critical mineral exports. When Trump imposed tariffs on Brazil, in retribution for the imprisonment of Bolsonaro, Lula stood his ground and the US eventually backed down, probably because of the risk that tariffs would increase the domestic prices of coffee and meat while pushing Brazil even closer to China. In the case of Venezuela, US extortion at gunpoint makes resistance more challenging. But it seems that coercion, on its own, is not a surefire way of winning the conflict between Great Powers.