The U.S. national debt is approaching record levels as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and currently stands at 100% of GDP, while interest costs are surging to new records and budget deficits remain elevated at around 6% of GDP.

High and rising deficits and debt can have many consequences, including that they can put upward pressure on inflation, boost interest rates, slow income growth, reduce fiscal space to respond to needs or emergencies, and weaken our national security. Perhaps most concerning, excessive debt could lead to a fiscal crisis.

A fiscal crisis – sometimes called a sovereign debt crisis – is a sharp economic shock or downturn caused or sparked by high levels of current or expected public borrowing. A fiscal crisis can take many forms but is most likely to occur if investors lose confidence in the Treasury market.

In this paper, we discuss and illustrate what a fiscal crisis might look like. The crisis types we survey – several of which could happen simultaneously – include:

Financial Crisis: Reduced confidence in U.S. Treasury markets could lead to a spike in interest rates, panic among traders, devaluation of assets, freezing or slowing of credit, and failure of key financial institutions.

Inflation Crisis: Attempts or fear of attempts to manage debt levels through monetization, artificially low interest rates, or financial repression could result in high and potentially spiraling inflation.

Austerity Crisis: Sharp tax increases and spending cuts enacted to stave off a fiscal crisis could create undue hardship, undermine demand, and push the economy into recession.

Currency Crisis: The U.S. dollar could face sudden and significant depreciation in response to fiscal stress and policy responses, resulting in destabilization of markets and the economy.

Default Crisis: Policymakers could explicitly or implicitly default on debt, including by failing to make debt payments or by restructuring existing debt.

Gradual Crisis: Living standards and fiscal and monetary flexibility could gradually erode in response to rising debt, potentially causing as much or more long-term damage than an acute crisis.

A fiscal crisis can be sparked by a variety of factors (see Box 3). Although the chances of a major fiscal crisis in the United States remain low in the near term, the likelihood and potential severity of a crisis rises with higher debt. Lawmakers would be wise to put the nation’s fiscal house in order to avoid any such crisis.

A Financial Crisis

Over time, high and rising debt could lead to a financial crisis. Specifically, reduced investor confidence over the sustainability of the U.S. fiscal outlook or significant strain on market plumbing could lead interest rates to rise sharply. Such a spike in interest rates could set off a panic, which would further perpetuate rate increases and wreak havoc on financial markets.

A sharp rise in interest rates on new debt would significantly reduce the value of existing debt, weakening the balance sheets of banks and other financial institutions, undermining confidence, and potentially triggering deposit withdrawals or funding stress. This could lead to a series of cascading failures at financial institutions, which could have ripple effects across the economy – making it difficult for individuals and businesses to make payments or receive loans and sparking a wave of defaults, rising unemployment, business failures, and foreclosures.

Box 1: Debt Could Spin Out of Control

As debt rises, it can become self-reinforcing, and a debt spiral can ensue. High debt pushes up interest rates and slows economic growth. This in turn can increase interest costs and reduce revenue, further pushing up debt. The more sensitive interest rates are to debt, the faster this debt growth can accelerate.

(1).png.webp.webp)

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

When a somewhat similar phenomenon occurred in 2007 – driven primarily by collapsing valuations of subprime mortgage-backed securities as opposed to U.S. debt – it led to a Global Financial Crisis where hundreds of financial institutions closed, housing values declined by one-quarter, output shrank 4%, unemployment rose to 10%, and the economy took years to recover.

Perhaps more comparable to a sovereign debt crisis – albeit on a much smaller scale – a modest but rapid increase in U.S. Treasury rates led to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, Silvergate Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank in 2023. Although policymakers were able to contain this set of failures, the technology industry faced setbacks, other banks reduced credit availability, and the Federal Reserve had to deploy emergency liquidity facilities.

In response to both the Great Recession and the 2023 banking crisis, the Federal Reserve, Treasury, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and other parts of the government responded aggressively. Although these institutions would also have some tools to address a fiscally driven financial crisis, attempts to use such tools would likely come at a much higher cost.

The additional borrowing needed to administer a financial bailout and economic stimulus package could make an underlying fiscal crisis worse. Meanwhile, rescue efforts from the Federal Reserve could undermine its ability to prioritize monetary policy objectives of stable prices and maximum employment. Either approach could spark inflation.

Fiscal irresponsibility has contributed to financial crises several times around the world, including in Argentina in 1998, Greece and others in Europe around 2009, and Brazil in 2016.

Although financial markets have been demanding higher interest rates from the U.S. in recent years, they fortunately appear able to bear current levels of U.S. debt. But markets are rarely predictable, and investor confidence can shift quickly. A panic could move the value of assets rapidly, threatening an interest-debt spiral and financial crisis. The higher and faster growing the U.S. debt burden, the more likely and more consequential such a crisis would be.

Box 2: Financial Crises and the Real Economy

Financial crises can inflict deep and lasting damage on the real economy. The 2007-2009 Global Financial Crisis reduced U.S. real GDP $850 billion (5%) below its estimated potential, and GDP remained below potential for almost a decade.

.png.webp.webp)

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

An Inflation Crisis

Deficits can directly contribute to inflationary pressures by increasing aggregate demand. Efforts to avoid a financial crisis or default without addressing underlying debt growth under a regime of fiscal dominance could further intensify inflation pressures, leading to an inflation crisis.

In the most extreme case, the government or Federal Reserve could monetize the debt – explicitly or implicitly printing money to finance the debt. In addition to purchasing existing Treasury securities, printed money could be used to fund interest and principal payments or to issue additional government debt without requiring outside buyers.

Short of monetizing the debt directly, the government may choose to lower its target interest rates, employ “yield curve control,” use its regulatory authority to increase external debt holdings (“financial repression”), or all of the above in an effort to reduce the cost of servicing the debt and/or support Treasury demand. Inflation could also be used to erode the real value of debt.

Any of these choices can lead to high and perhaps spiraling inflation. Significantly increasing the money supply, either by printing money or keeping interest rates artificially low, reduces the value of dollars currently in the economy and puts upward pressure on prices. When more money chases the same amount of goods and services, inflation results. These choices can also de-anchor inflation expectations as market actors lose confidence in the Federal Reserve’s ability or willingness to keep inflation near its target rate.

Although this higher inflation will reduce the value of current debt, it may actually worsen the future debt outlook as investors demand higher interest rates on future borrowing and various government programs and tax provisions automatically adjust for inflation. In this case, efforts to inflate away current debt might lead to expectations that the same efforts will be repeated for future debt, which would further worsen the inflation outlook.

Even just the fear of debt monetization or general fiscal dominance – a fear that is likely to grow as debt does – could lead to an inflation crisis where market actors bake future inflation into their expectations, increasing inflation risks and limiting the effectiveness of accommodative policies.

Box 3: What Would Spark a Fiscal Crisis

With the national debt approaching record levels, there is little precedent to understanding when the U.S. debt burden will become too large to bear. While it is unlikely there is a specific predictable tipping point, any number of events or actions could trigger a fiscal crisis.

Fiscal panic could begin even without a spark. But some possible catalysts include:

A Recession: The national debt has grown by a combined 65% of GDP over the past two recessions and recoveries – due both to the impact of the recessions on revenue and output and to the cost of the fiscal response. With fiscal space waning, a future recession could push the country’s debt burden “over the edge,” precipitating a fiscal crisis. This would be more likely to occur under a supply-shock driven recession, where inflation and interest rates remain higher.

The Enactment or Allowance of Large New Borrowing: A massive new tax cut, spending increase, or abandonment of fiscal rules could spark a fiscal crisis – both through the additional borrowing itself and by sending the signal that the U.S. is indifferent to how much it borrows. For example, if policymakers chose to fund Social Security with a general revenue transfer, it might signal a willingness to engage in massive new borrowing. A proposed tax cut in the United Kingdom in 2022 nearly sparked a fiscal crisis.

A Poor Treasury Auction: During a Treasury auction, U.S. marketable securities are bid on by investors, and a poor auction is indicative of weak demand. Although requirements on primary dealers make a literal “failed auction” virtually impossible, recurring poor auctions could spark a panic in financial markets and ultimately a fiscal crisis.

A Drop in Foreign Demand for U.S. Debt: Foreign investors could decide to stop purchasing as much U.S. debt due to U.S. policy or instability, more attractive investments in other countries, or as a foreign policy tool to weaken the U.S. This could spark a Treasury sell-off and fiscal crisis.

A Debt Limit Breach: The federal government is limited in how much debt it can borrow without legislation to raise the “debt limit.” Failure to raise the debt limit could lead the U.S. to default on its interest payments or non-debt obligations, either of which could spook markets and cause a fiscal crisis. Even coming close to default could be damaging.

A Debt-Interest Spiral: When the interest rate paid on debt exceeds the economic growth rate (R>G), debt will rise indefinitely even with small primary deficits. High debt pushes up interest rates and reduces growth, which can create a further wedge between R and G and ultimately set off a dangerous debt spiral. If markets perceive the U.S. to be too far into the spiral to take corrective action, a fiscal crisis could result.

Signals of Fiscal Dominance: If the Federal Reserve makes clear it will use monetary policy to address rising debt at the expense of its inflation and unemployment mandates, expectations of higher inflation and a weaker currency could spark an inflation crisis or other type of fiscal crisis. Among actions that might lead to this expectation include changes that undermine the Fed’s independence.

An Austerity Crisis

The best way to avoid a fiscal crisis is to enact the necessary deficit reduction – thoughtful and pro-growth spending cuts and/or tax increases – to reduce budget deficits to manageable levels. In periods of higher inflation or high short-term interest rates, a more rapid implementation can be beneficial and can help keep prices and yields at bay.

However, the economy may be unable to absorb very large amounts of deficit reduction all at once. Excessively large and abrupt deficit reduction – particularly if enacted during a period of economic weakness and/or low short-term interest rates – can drive the economy into a deep recession. Such an “austerity crisis” may increase joblessness, reduce incomes, weaken output, and undermine or delay efforts to wrestle debt under control.

When the economy is operating at or below its potential, large tax increases or spending cuts can significantly reduce near-term output by lowering the demand for goods and services. Lower consumption resulting from this austerity can then reverberate in the economy through a multiplier effect, significantly weakening national income and output.

While modest or incremental deficit reduction can generally be countered by monetary policy and/or absorbed by the economy through a temporary but manageable slowdown in economic growth, sharp austerity can lead to an economic contraction. This is particularly true if short-term interest rates are (or become) near zero, leaving the Federal Reserve with fewer tools.

As an illustrative example, 5% of GDP in sharp austerity could turn 2% real growth into a 3% contraction, assuming a multiplier of 1x. If the Federal Reserve only had limited ability to counteract this contraction with lower interest rates, the recovery might be prolonged. And the recession itself might be self-reinforcing as layoffs and business closures left less money to spend and reduced consumer and investor confidence. The economic hit could be even more significant if the austerity included cutting public investments and raising taxes on work and investment.

The contraction itself would also undermine some of the fiscal savings from the deficit reduction by reducing tax collection and increasing the debt-to-GDP ratio as a result of lower GDP. To the extent this created pressure for further austerity, it could deepen and lengthen the crisis. The government could respond by borrowing more for temporary “stimulus measures,” which could scare financial markets worried about the country’s ability to put its fiscal house in order.

Greece experienced such an austerity crisis after the Global Financial Crisis when economic weakness caused an untenable spike in borrowing and bond yields, which lead to a painful set of austerity measures that decimated the economy and exploded the unemployment rate. Portugal and Spain experienced somewhat similar, albeit less severe, crises.

In the case where rapid debt reduction is needed to restore sustainability, austerity might be the best of a set of bad options. But the unfortunate result could be a deep and prolonged recession.

A Currency Crisis

High and rising debt and deficits can weigh on a nation’s currency by elevating inflation risk, reducing market stability, and weakening fiscal credibility. Naturally, interest rates rise in response to offset currency weakness and reduced demand for government securities – which can further worsen the fiscal outlook and create a self-reinforcing cycle. Forced actions to lower short-term rates, cap long-term yields, or monetize debt can debase the currency. Currency debasement can also put upward pressure on import prices, degrade geopolitical power, and undermine economic stability.

The U.S. dollar (USD) is the world’s leading reserve currency, representing the majority of global foreign exchange reserves held by central banks. Additionally, the dollar is the dominant currency in global trade and international finance, and Treasury securities ultimately serve as global risk-free benchmark rates. The USD has served as the dominant reserve currency since the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944, in large part due to the size and stability of the U.S. economy. The strong dollar has helped to further fuel U.S. economic growth by putting downward pressure on borrowing costs – benefiting the federal government, businesses, and consumers. A strong dollar also means imports are less expensive, though at the cost of less competitive exports and suppressed foreign demand.

Were the U.S. dollar to weaken significantly in response to reckless fiscal policy and currency debasement, it would become more difficult to attract U.S. Treasury investors and in turn investors in the U.S. at large. Compensating for a depreciating dollar with higher interest rates would just exacerbate the fiscal crisis.

With a weakening currency, geopolitical power could fall. Less stability in the dollar’s strength may encourage diversification away from USD assets by both foreign official and private investors, reducing the dollar’s role in global finance. The U.S. government’s ability to track illicit activity, freeze assets, and enforce sanctions is heavily dependent on the international standing of the U.S. dollar. As well, a weakening of foreign demand for USD assets due to dollar instability would push Treasury yields higher and further erode investor confidence generally.

A decline in trade, or a full restructuring of trade where the U.S. shifts to rely more heavily on exports and domestic production, is another possible outcome. If the dollar loses significant value, the U.S. would not be able to lean on outsourced labor and resources as it has historically – forcing a restructuring of the economy.

Currency crises have occurred many times in history, often in countries with fixed or semi-fixed exchange rates like Argentina in 1991, the United Kingdom in 1992, and Mexico in 1994. Floating currency crises have also occurred, such as Iceland in 2008 and the United Kingdom in 1976.

The fact that the USD is the world’s dominant reserve currency probably makes a severe currency crisis less likely but also makes the potential consequences far more severe and far-reaching.

A Default Crisis

Although unlikely, the most straightforward fiscal crisis would take the form of a default on U.S. debt. The U.S. federal government currently owes about $31 trillion to the public, including banks and financial institutions, state and local governments, foreign governments, businesses, individuals, and the Federal Reserve. This debt is held largely in interest-bearing notes, bills, and bonds with terms ranging from one month to 30 years. A default crisis would occur if the federal government failed to make principal or interest payments.

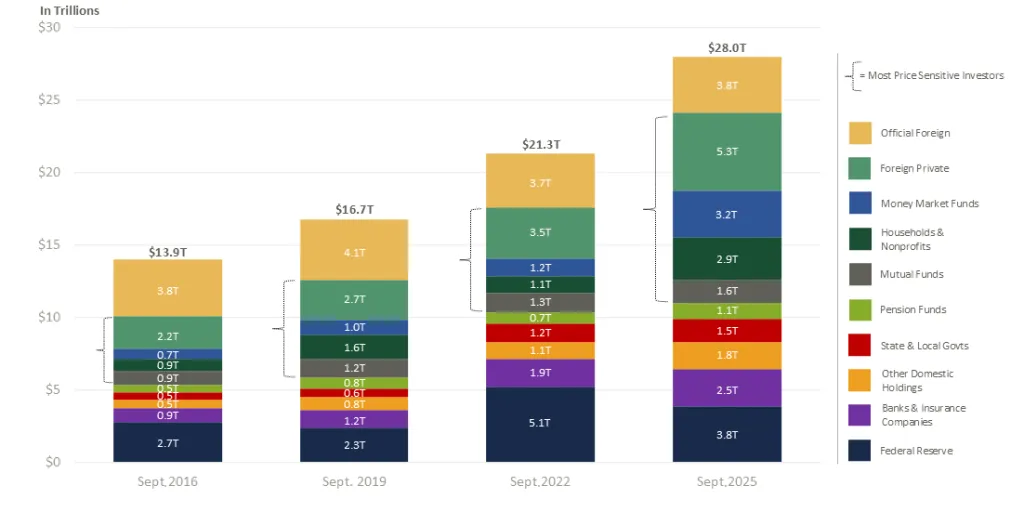

Box 4: Holders of US Debt Have Shifted Over the Decade

As the U.S. accumulates more debt, it must continue to attract buyers of that debt. Currently, about 33% of the debt is held by foreigners, 53% by domestic holders, and 14% by the Federal Reserve. Less than a decade ago, in 2016, 44% was held by foreigners, 36% by domestic holders, and 20% by the Federal Reserve.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Financial Accounts of the U.S. (z.1), Table L210 (Treasury Securities).

Note: Table includes marketable Treasury securities held by the public. Data current as of January 2026. Figures may not sum due to rounding.

Among holders of Treasuries, some – such as mutual funds, money market funds, households and nonprofits, and foreign private entities – are more sensitive to the interest rate than others in making lending choices. We estimate roughly half of the debt ($13 trillion) is held by price sensitive investors, up from one-third ($5 trillion) nine years ago.

The consequences of such a default could be catastrophic. In the case of a large-scale default, U.S. debt around the world – the backbone of the global financial system – would experience large valuation losses and have its status as a reliable safe asset undermined. Banks would fail, credit markets would freeze, stock markets would crash, pension funds would default, and countries around the world would enter deep recessions. The U.S. would find itself unable to borrow at reasonable interest rates, potentially forcing austerity and accommodative monetary and debt management policies. A Moody’s Analytics report from 2023 estimated that even a temporary default, lasting only a few weeks and not driven principally by excessive debt, would reduce output by 4%, increase joblessness by 6 million, and wipe out one-third of the stock market.

A partial default might be less damaging but could still spark a crisis. For example, if the U.S. defaulted on only some of its obligations as they came due, if it discontinued interest but continued paying principal, or if it undertook “debt restructuring” to reduce the amount of debt that had to be repaid, markets would still interpret this as a breakdown in U.S. creditworthiness, which could further devalue current debt and make future debt harder to issue.

A number of countries throughout history have defaulted on their debt. In the early 1980s, Mexico announced it could no longer service its debt, leading to panic among banks in the region and a sparking a debt crisis that spread to Brazil, Peru, Argentina, and other countries in the area. In 1998, Russia defaulted on its short-term debt, a move that helped to drive its economy into a deep recession and led to years of distrust and disinvestment from many countries. And in 2001, Argentina defaulted on roughly $100 billion of its debt, weakening its economy and undermining additional borrowing capacity.

The United States is very unlikely to default on its debt. Countries that borrow in their own currency are never technically required to default (though some have) because they can always print money if necessary (which could spark an inflation and/or currency crisis). The United States is also a very wealthy and high-income country with deep capital markets, significant tax capacity, strong institutions, and significant hard and soft power abroad.

Nonetheless, as debt and interest costs rise, default could become a more attractive option relative to the alternatives. In a debt spiral situation, higher debt can lead to higher interest rates and can expand interest costs, which can lead to even higher debt. At some juncture, the pace of interest-driven debt growth may be so rapid that policymakers view some form of default – perhaps in the form of debt restructuring – as the best, easiest, and least costly path forward.

Default could also occur in the context of a political standoff. Federal borrowing is subject to a “debt limit” that policymakers raise or suspend occasionally. Raising the debt limit provides a good opportunity to make fiscal reforms, but failure to agree on a debt limit increase could lead to a dangerous default.

A Gradual Crisis

Although high and rising debt could lead to a sharp and acute crisis, it could also gradually erode standards of living in ways that can prove just as damaging over time. Rather than sparking a rapid rise in interest rates, inflation, currency debasement, and/or economic instability, continued fiscal deterioration may instead lead to an incremental worsening of these and other conditions. This gradual erosion may occur on its own or be guided by efforts from policymakers to avert a sharp crisis – which may succeed in smoothing the crisis over time but not truly averting it.

Specifically, high and rising debt can lead to higher interest rates, slower income and output growth, losses in economic dynamism, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased need to raise taxes and cut spending in the future. Although they would occur gradually, the impact could eventually be larger in size than a sharp crisis.

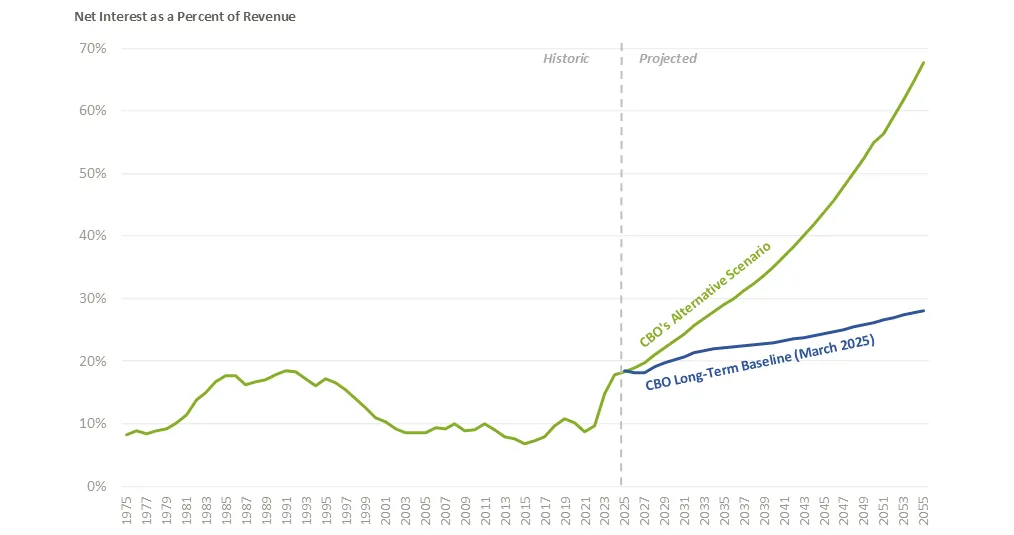

Box 5: Rising Interest Costs Raise Financing Challenges

As debt and interest rates rise, a growing share of government revenue must be used to finance interest costs. As recently as 2021, interest costs consumed less than 10% of federal revenue. That share has nearly doubled – last year, federal interest costs consumed a near-record 18% of revenue.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

*Alternative Scenario assumes revenue and non-entitlement spending revert to historic levels.

Looking forward, interest is projected to consume a growing share of revenue. Under CBO’s pre-OBBBA long-term outlook, interest was projected to consume nearly 30% of revenue by 2055. Under an alternative scenario where revenue and non-entitlement spending returned to historic averages, we estimate interest would consume almost 70% of revenue by 2055.

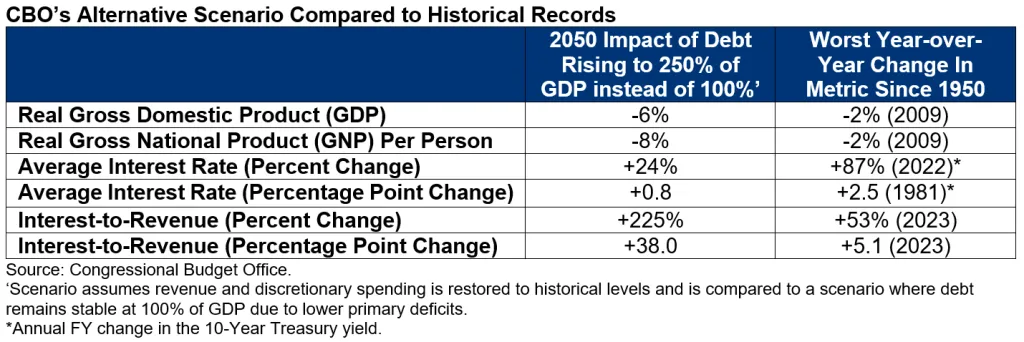

In the Spring of 2025, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) modeled a scenario under which debt would approach 250% of GDP within a quarter-century without causing a sharp contraction – effectively, they modeled a gradual crisis. Compared to keeping the debt stable at 100% of GDP, CBO found that by 2050 – after 25 years – real income per person (GNP) would be 8% lower, average interest rates on government debt would be 24% (0.8 percentage points) higher, and interest payments would consume an additional 225% (38 percentage points) of revenue. Annual economic growth under this scenario would slow by about one-third.

Although these effects would happen gradually, some would be larger in size than any acute change in the past 75 years. For example, GDP and GNP have never shrunk by more than 2% year-over-year since 1950 – meaning a fiscal crisis would need to shrink output three times as much as the largest modern recession to match the incremental impact of letting debt rise indefinitely.

Japan provides a possible case study for this gradual crisis, having sustained extremely high levels of debt for several decades. Although the country has avoided an acute crisis as a result, real GDP has grown only 10% (0.5% per year) over the past two decades. The monetary and financial policies undertaken to avoid an acute crisis in Japan have also starved the economy of dynamism and investment and left it in a precarious position. Other countries, from France to Italy to the United Kingdom, are experiencing slow growth and inflexible fiscal policy, driven in part by their high rates of borrowing.

In some ways, a gradual crisis could be more severe and more difficult to address than any of the aforementioned crises. While the political system has a track record or reacting to deadlines or sudden crises, it may not be as well equipped to respond to slow-moving economic changes without a clear tipping point.

Conclusion

The United States is deeply indebted, and its finances are on an unsustainable long-term trajectory. It is impossible to know when a fiscal crisis will occur, what will spark it, or what exactly it will look like. Without a course correction or major change in circumstance, however, some form of crisis is almost inevitable.

If the national debt continues to grow faster than the economy, the country could ultimately experience a financial crisis, an inflation crisis, an austerity crisis, a currency crisis, a default crisis, a gradual crisis, or some combination of crises. Any of these would cause massive disruption and substantially reduce living standards for Americans and people across the world.

Already, the U.S. is facing consequences from excessive debt. Excessive borrowing was a key driver of the recent surge in inflation and subsequent rise in interest rates, and real incomes are lower today than they otherwise would be as a result of the “crowd out” of past investment. Meanwhile, the cost of interest on the debt grew to roughly $1 trillion last year, which is more than the federal government spent on defense and about as much as it spent on Medicare. These high interest payments leave fewer resources for new spending initiatives and tax cuts. And with debt at 100% of GDP, the U.S. has less fiscal space than any time in history in case of another war, pandemic, or recession. A fiscal crisis would substantially worsen most or all of the costs of debt.

The best insurance against a fiscal crisis is a thoughtful pro-growth deficit reduction package that begins promptly and phases in over time. Gradually reducing deficits toward 3% of GDP would put the national debt on a slow downward path, reassuring markets that the United States will make good on its obligations and dramatically reduce the likelihood that a future crisis occurs.

Policymakers should work together to develop and enact a plan to achieve this goal by lowering health care costs, securing federal trust funds, reducing spending, and raising revenue. Absent a full plan to achieve this goal, Congress should work to develop a Break Glass Plan in case of another economic shock.