MELBOURNE, Australia — The bittersweet story of Monica Seles’ 1996 Australian Open title actually begins in 1994, when Seles has yet to decide how to spend the rest of her life.

She is a year removed from a spring day in Hamburg, Germany when a deranged fan of Steffi Graf stormed onto the court during a changeover at the Citizen Cup and stabbed Seles between her shoulder blades.

Seles is 19 when that happens, an eight-time Grand Slam winner seemingly destined to become the greatest female tennis player in history. A year later, Seles is physically recovered for the most part but still emotionally damaged. She is thinking about going to college. A tennis court doesn’t feel like a safe space any more.

She talks it through with her father, Károlj, the person who introduced her to the sport in the former Yugoslavia. The person who brought her to Florida, so she could train far away from her country, at the time a land on the edge of conflict and war. The person who taught her those two-handed strokes. Károlj Seles, a former track and field athlete who studied sport science and became a cartoonist, retained his geniality even as he became a tennis parent. He was her rock.

Do whatever you want to do, he tells her.

She ponders her options. She arrives at a conclusion. She will do whatever she wants to do.

“I’m not going to let one individual take away from me something that I love,” Seles said during a recent interview. “I said, ‘OK, I still love to play tennis. I still love to compete. What’s there to lose?”

And then it’s January of 1996 in Melbourne, and she is on Rod Laver Arena, one win away from a ninth Grand Slam title.

Thirty years later, Seles is still not really sure how she got there.

Monica Seles in Sydney in January 1996, just before the Australian Open. (Torsten Blackwood / AFP via Getty Images)

It’s silly to try to describe the bolt of lightning that Seles became in the early 1990s. One moment, Graf looks like she’s going to win every tournament for another decade. Then this teenager, who screams as she slingshots the ball all across the court, is displacing Graf as the world No. 1 and collecting Grand Slam titles by the armload.

One in 1990, three in 1991, another three in 1992, and the first one of 1993. She’s just too good.

Then she gets stabbed. Then she’s gone. Then she’s going to come back.

In early 1995, she gets back on the tennis court. Her father guides the process, but Seles has someone else, too. Bob Kersee, the husband and coach of Jackie Joyner-Kersee, the two-time gold medalist in the heptathlon, pitches in.

“He believed in me so much,” she said.

Around March of 1995, Seles looks at the calendar and circles the U.S. Open in late summer in New York. She figures she might have her body, her mind and her game back by then – roughly two and a half years after the stabbing.

But how does player get ready for a comeback like this? A few months of hard training in the Florida sun can only do so much. The real practice that Seles needs is the part that players are supposed to find easy: Walking out in front of a crowd again. How will she react? Will her eyes scan the seats for danger?

Seles connects with Martina Navratilova, who, nearing the end of her singles career, agrees to play an exhibition match with her in Atlantic City, N.J.

The nearly 8,000 fans give Navratilova a rousing welcome. Then Seles hears her name and walks out.

“Oh my god,” she said, recalling the noise.

She knows she has made the right decision, even with so many mixed emotions. She is especially self-conscious about her weight, at a time when sportswriters have no compunction about offering their opinions on women’s bodies in headlines and standfirsts.

She travels with a bodyguard. She knows how much extra security is around. So she does what her father has always taught her to do on the court: look at the ball.

“My stabbing didn’t take that away,” Seles said.

Sometimes she is so focused on the ball that she forgets who is on the other side of the net. All she knows is that a slice backhand or topspin forehand is coming at her. That’s what matters, the information she uses to launch into the ball and catapult it into the corners.

It’s 10 days after the exhibition with Navratilova and Seles is heading to the Canadian Open in Toronto. How good is she? How much better is she than just about everyone else? She wins the tournament, dropping two games in the last two rounds, and then she is off to the U.S. Open to plow through through the draw without losing a set, until Graf beats her in the final 7-6(6), 0-6, 6-3.

By the time she is done, her knee is banged up. She needs a break. She takes the rest of the year off. She circles a new date on her calendar: The start of the Australian Open in January.

She begins in Sydney. Another steamroll, until Lindsay Davenport takes her to three sets in the final.

Then she leaves for Melbourne, one of her favorite places in the world. Seles is an animal lover. Between matches, she visits the kangaroos and koalas at the famous zoo. She loves the beach and sneaks in an hour in the sand and water on her off-days.

She is in her happy place, a place where she wins titles: three Australian Opens, from 1991 to 1993. She is favorite again, after so long being the underdog, so long not knowing whether she would ever again be either.

“I just remember extreme amounts of pressure, ooo-la-la,” she said.

Her stomach turns on the drives from the hotel to the courts and in the news conferences, where journalists remind her she has not lost in Melbourne since 1990. She reminds them she has not played there since 1993, months before Hamburg and everything that comes with it.

She feels the weight of the expectations more than she remembers her opponents from match to match. She opens the newspaper in the morning and sees articles questioning whether she is too heavy to win the tournament.

There is one long match, against Chanda Rubin in the semifinals. Seles loses the first set, then comes back to win 7-5 in the third.

She said she saw Rubin recently.

“I said, ‘Chanda, you should have beaten me.”

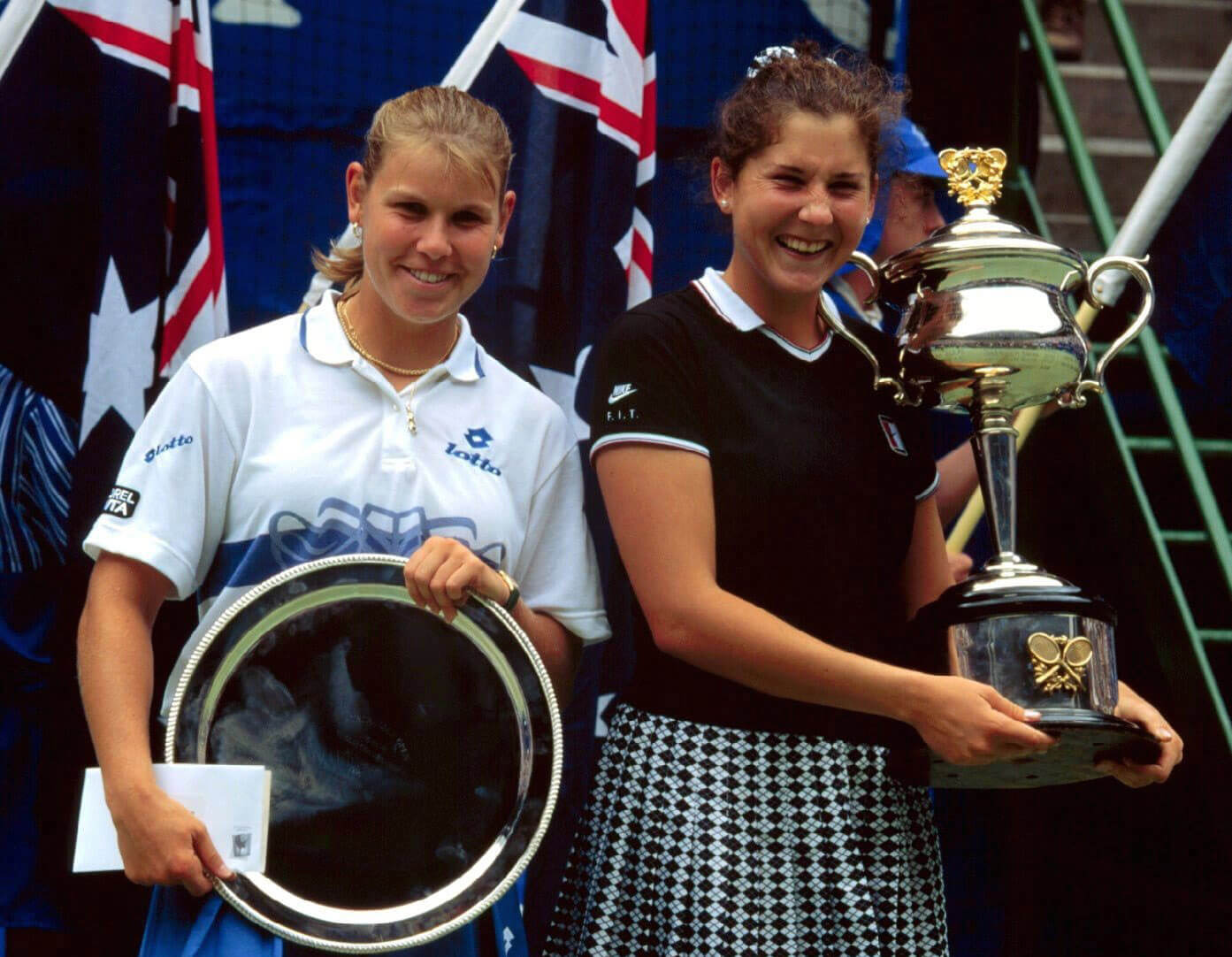

Even the final is a bit of a blur. She plays Anke Huber and wins 6-4, 6-1. She barely celebrates when Huber’s last backhand sails wide. She sits alone in the locker room when it is over.

“‘Oh, my God, I really did this,’” she remembers thinking. “The perseverance, the nights, the days when you cry, depression, all the things that when you question yourself and your path and everything.”

She and Huber end up at the same nightclub later that evening. They dance the night away together.

Anke Huber (left) and Monica Seles (right) after the 1996 Australian Open final.

Monica Seles never won another Grand Slam title. A new generation arrived and supplanted her, led by Martina Hingis, Davenport and two sisters from Compton, Calif. named Venus and Serena Williams. This is what happens in tennis, and sometimes it happens fast.

Thirty years on, of the nine Grand Slam titles she won, the two she cherishes most are her first and her last, but not for the reason anyone might think.

About a month after her triumph, her father was diagnosed with cancer. He died two years later.

“My dad meant so much to me, both on court and off court, that for me, tennis for a bit just wasn’t the same. Probably ever,” she said.

She couldn’t separate losing her father from the sport that she had stood ready to dominate. Her fitness declined. It was still a different time, when depression and therapy were seen as signs of sporting weakness. Seles plowed through the pain, but never really processed it.

Now she has. And through it all, she and her father had what now feels to Seles like one last brief, shared respite of joy. In Melbourne.