Like a bomb cyclone, a polar vortex, or an atmospheric river, a heat dome is a meteorological phenomenon that feels, well, a little made up. I hadn’t heard the term before I found myself bottled beneath one in the Pacific Northwest in 2021, where I saw leaves and needles brown on living trees. Ultimately, some 1,400 people died from the extreme heat in British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon that summer weekend.

Since that disaster, there have been a number of other high-profile heat dome events in the United States, including this week, over the Midwest and now Eastern and Southeastern parts of the country. On Monday, roughly 150 million people — about half the nation’s population — faced extreme or major heat risks.

“I think the term ‘heat dome’ was used sparingly in the weather forecasting community from 10 to 30 years ago,” AccuWeather senior meteorologist Brett Anderson told me, speaking with 36 years as a forecaster under his belt. “But over the past 10 years, with global warming becoming much more focused in the public eye, we are seeing ‘heat dome’ being used much more frequently,” he went on. “I think it is a catchy term, and it gets the public’s attention.”

Catching the public’s attention is critical. Heat is the deadliest weather hazard in the U.S., killing more people annually than hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, or extreme cold. “There is a misunderstanding of the risk,” Ashley Ward, the director of the Heat Policy Innovation Hub at Duke University, told me. “A lot of people — particularly working age or younger people — don’t feel like they’re at risk when, in fact, they are.”

While it seems likely that the current heat dome won’t be as deadly as the one in 2021 — not least because the Midwest and Southeastern regions of the country have a much higher usage of air conditioning than the Pacific Northwest — the heat in the eastern half of the country is truly extraordinary. Tampa, Florida reached 100 degrees Fahrenheit on Sunday for the first time in its recorded history. Parts of the Midwest last week, where the heat dome formed before gradually moving eastward, hit a heat index of 128 degrees.

Worst of all, though, have been the accompanying record-breaking overnight temperatures, which Ward told me were the most lethal characteristics of a heat dome. “When there are both high daytime temperatures and persistently high overnight temperatures, those are the most dangerous of circumstances,” Ward said.

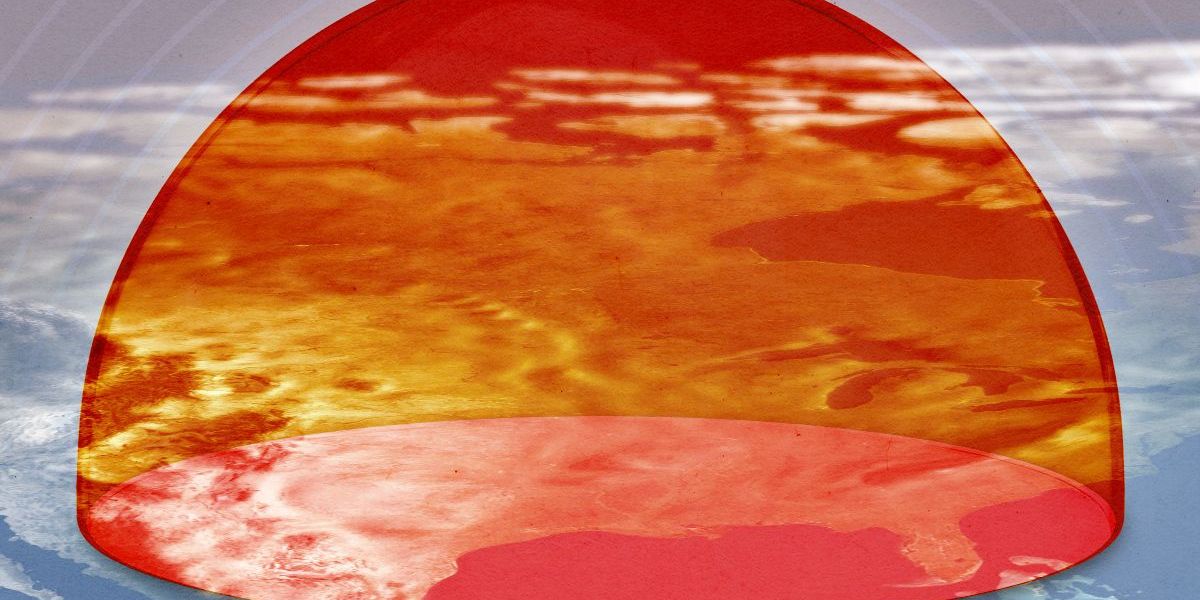

Although the widespread usage of the term “heat dome” may be relatively new, the phenomenon itself is not. The phrase describes an area of “unusually strong” high pressure situated in the upper atmosphere, which pockets abnormally warm air over a particular region, Anderson, the forecaster, told me. “These heat domes can be very expansive and can linger for days, and even a full week or longer,” he said.

Anderson added that while he hasn’t seen evidence of an increase in the number of heat domes due to climate change, “we may be seeing more extreme and longer-lasting heat domes” due to the warmer atmosphere. A heat dome in Europe this summer, which closed the Eiffel Tower, tipped temperatures over 115 degrees in parts of Spain, and killed an estimated 2,300 people, has been linked to anthropogenic warming. And research has borne out that the temperatures and duration reached in the 2021 Pacific Northwest heat dome would have been “virtually impossible without human-caused climate change.”

The link between climate change and heat domes is now strong enough to form the basis for a major legal case. Multnomah County, the Oregon municipality that includes Portland, filed a lawsuit in 2023 against 24 named defendants, including oil and gas companies ExxonMobil, Shell, and BP, seeking $50 million in damages and $1.5 billion in future damages for the defendants’ alleged role in the deaths from the 2021 heat dome.

“As we learned in this country when we took on Big Tobacco, this is not an easy step or one I take lightly, but I do believe it’s our best way to fight for our community and protect our future,” Multnomah County Chair Jessica Vega Pederson said in a statement at the time. The case is now in jeopardy following moves by the Trump administration to prevent states, counties, and cities from suing fossil fuel companies for climate damages. (The estate of a 65-year-old woman who died in the heat dome filed a similar wrongful death lawsuit in Seattle’s King County Superior Court against Big Oil.)

Given the likelihood of longer and hotter heat dome events, then, it becomes imperative to educate people about how to stay safe. As Ward mentioned, many people who are at risk of extreme heat might not even know it, such as those taking commonly prescribed medications for anxiety, depression, PTSD, diabetes, and high blood pressure, which interfere with the body’s ability to thermoregulate. “Let’s just say recently you started taking high blood pressure medicine,” Ward said. “Every summer prior, you never had a problem working in your garden or doing your lawn work. You might this year.”

Air conditioning, while life-saving, can also stop working for any number of reasons, from a worn out machine part to a widespread grid failure. Vulnerable community members may also face hurdles in accessing reliable AC. There’s a reason the majority of heat-related deaths happen indoors.

People who struggle to manage their energy costs should prioritize cooling a single space, such as a bedroom, and focus on maintaining a cool core temperature during overnight hours, when the body undergoes most of its recovery. Blotting yourself with a wet towel or washcloth and sitting in front of a fan can help during waking hours, as can visiting a traditional cooling center, or even a grocery store or movie theater.

Health providers also have a role to play, Ward stressed. “They know who has chronic underlying health conditions,” she said. “Normalize asking them about their situation with air conditioning. Normalize asking them, ‘Do you feel like you have a safe place to go that’s cool, that you can get out of this heat?’”

For the current heat dome, at least, the end is in sight: Incoming cool air from Canada will drop temperatures by 10 to 20 degrees in cities like Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., with lows potentially in the 30s by midweek in parts of New York. And while there are still hot days ahead for Florida and the rest of the Southeast, the cold front will reach the region by the end of the week.

But even if this ends up being the last heat dome of the summer, it certainly won’t be in our lifetimes. The heat dome has become inescapable.