Are Carbon Markets Financially Efficient?

About 18 months ago I wrote a post analyzing the expected supply and demand for California carbon allowances under different scenarios. The main hypothesis of this work (joint with Aaron Smith, Wuzheqian Xiao, and Julie Witcover) was that the looming uncertainty of the cap-and-trade program, which at the time was authorized only through 2030, was keeping allowance prices depressed. Our calculations at the time indicated that the California market would have a surplus of allowances through 2030, so if the market ended at that time those allowances would have very little value.

We expected the story to change, however, if California’s program was extended past 2030. That was because the aggregate surplus of allowances looked like it would become a deficit somewhere around the mid 2030s (see chart above). This was the case even though we assumed less ambitious carbon reduction goals than what was eventually adopted. After 2033 or so, sharp declines in the carbon cap would require ever more rapid reductions of emissions, or else the price would settle in at the allowance price ceiling. I fully expected that, if the program were extended past 2030, the market would start to price in the prospect of a looming, if somewhat distant, shortage of allowances and start driving up near-term demand for allowances, which, with some restrictions, can be banked indefinitely and cashed in at a later date. In other words, I expected firms would start buying up allowances at today’s low prices and banking them for the future, thereby increasing prices in the near term.

Over the last year, the market has simply not cooperated with my cogent analysis. California’s legislature, at the urging of Governor Newsom, and perhaps in response to President Trump’s vague threats against the program, passed legislation extending the program to 2045. The legislation codified an extremely aggressive schedule of emissions reductions over the next 20 years. More recently, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) released a proposal that would remove a further 118 million tons from the market between 2027 and 2030.

In response to all this news the allowance market did, well, nothing. The price for vintage 2026 allowances started the year around $33/ton, dropped below $30 at midyear, climbed up to $34 around the time of the program’s extension in August 2025, but finished the year back down at $30/ton.

Data for DEC26 vintage 2026 California Carbon Allowance from Intercontinental Exchange: http://www.ice.com

So, in summary, our model said carbon prices are likely to be near the price ceiling of over $150/ton (in 2024 dollars) by the mid 2030’s, and that current day prices would be bid up to just a little below that in near-term. Instead, you can buy allowances for around $30/ton today.

I just hate it when the world doesn’t behave like my model.

So what’s going on? First let me say that I have ABSOLUTELY NO inside knowledge of what’s going on with this market. I also have no financial stake in this market. The following is just speculation on my part as I am trying to understand this market’s dynamics. Suggestions from readers would be welcome. I can think of several possibilities.

Explanation 1: It’s the Model

Maybe our model is wrong. Now, it goes without saying that this is the least credible explanation ….

More seriously, while our model has a lot of technical bells and whistles to it, this really comes down to how fast you think California can reduce its carbon emissions, and at what cost. While the carbon cap was less binding, and some believe too lax, during the 2010s, the trajectory of the cap sharply declines from 2020 onward. Further, the declines in emissions during the 2010s were dominated by the electricity sector, particularly imported electricity. This was the low-hanging fruit. Large reductions in industrial and residential emissions are likely to be slower and more costly.

The key aspect of California’s carbon market is that there is a price floor and a price ceiling. Our model estimates that the amount of carbon abatement induced by higher carbon prices, even at the price ceiling, is not sufficient to keep up with the reduction goals of the program. One way the market could produce carbon prices lower than our model is if there is a lot more abatement possible at prices in the $50 – $150/ton range than we thought.

How plausible is that? Another way to look at this question is to ask, why were prices for vintage 2026 allowances close to $48/ton in early 2024 and barely more than half of that today? Has there been new information that makes it clear California will more easily stay under its cap? Let’s recount some of the pertinent events since 2024.

a) The Trump administration eviscerates regulations supporting EVs and improved vehicle fuel economy. California and other states are still disputing these moves.

b) Almost all of the clean energy provisions in the IRA, including subsidies for EVs, home electrification, and renewable electricity get repealed.

c) Under pressure from tariffs and the changing regulatory landscape, the EV market stagnates even in California.

d) California commits to either cutting its current emissions from 267 mmTons/year in 2025 to only 30 mmTons/year in 2045 or, if it can’t reach these levels, letting its carbon price follow a trajectory that starts at over $100/ton in 2026 and rises to almost $200/ton by 2040.

If this market were behaving rationally, the price movements over the last year imply that compliance with our future cap now looks less costly than it did two years ago. Yet almost all the news since 2024 points toward an environment where complying with the carbon cap will be more difficult, not less.

Explanation 2. Its the Risk

Firms and speculators may believe it’s too risky to buy permits and plan on holding them to sell in the future. Trump could kill the program. California could back off its goals. A meteor could hit the earth. Cold fusion could be commercialized. You get the point.

In a way, if you believe our model, this explanation is almost definitionally true. Firms are not willing to risk holding permits even for what look like potentially enormous returns. But the implied risk aversion is pretty staggering. The price ceiling in 2035 will be close to $150/ton plus inflation. For an investor buying permits at $30/ton today, that would constitute more than a 20% annual real return. I was curious about what kinds of investments require that amount of return to draw capital. Some of the riskier sovereign debt out there runs up to 20%. California carbon allowances are somewhere between Ghana and Egypt on the expected return, except that carbon allowances have no currency and less inflation risk because the floor and ceiling prices are pegged to inflation.

For most of these international bonds, the downside risk is default. For a cap-and-trade market, I would think the downside risk is less extreme. Even if you think the Federal government could somehow kill a state program like California’s cap and trade, if it were completely eliminated I would imagine that outstanding permits would be repurchased. When Ontario left the WCI market (of which California is the largest member) participants holding unused allowances were compensated, at something like the average auction price over previous auctions.

For California’s carbon market a more realistic scenario might be a relaxation of the regulation, either by increasing emissions caps or allowing more controversial compliance instruments like offsets or dairy gas. Another possibility is that the price ceiling may be set at a lower level, or more plausibly, frozen. However, the price ceiling is over $100 this year, so upside price potential is still large even if the current level is held fixed. Further, the market still has a floor price that is also increasing at 5% real per year. This means the lowest the price would be in 2035 would be about $41 plus inflation. In other words, the downside risk (as long as the program continues to exist) would be getting “only” a 4% real return. Inflation protected treasury bonds are yielding a little under 2% right now.

Risk is clearly a factor, but I have trouble believing this risk is being arbitraged in any kind of sophisticated and rational way.

Explanation 3: It’s the Refineries

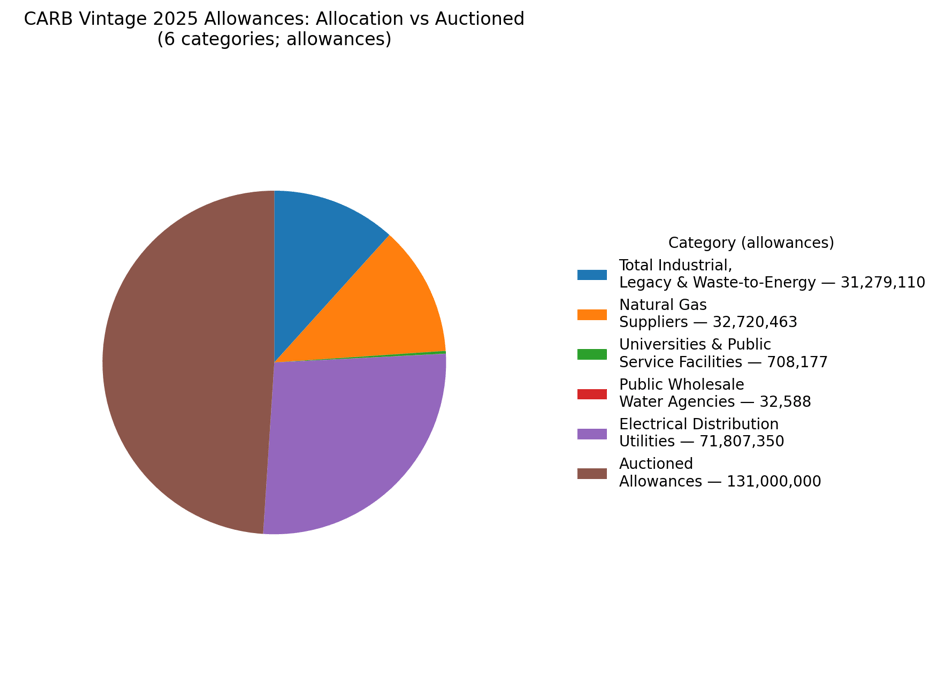

This is pure, uninformed, speculation on my part. Consider two related facts. First, the combustion of gasoline and diesel constitutes more than half of California’s capped emissions, about 126 mmTons in 2023. Most of the other half of emissions are covered through allocated, rather than auctioned, allowances.

In other words, the firms with the largest requirements to purchase allowances, by far, are the ones that sell gasoline. According to my calculations, about 197 mmTons of California allowances were sold in the 4 auctions in 2025 (Electricity allocations – the purple sliced -are consigned into the auction). If emissions from transportation fuels remained steady from 2023, then about 60% of the allowances sold in 2025 would be needed by sellers of transportation fuels to comply with their obligation to cover the tailpipe emissions associated with the fuels they sell.

However, two of those firms, Valero and Phillips 66, are closing their refineries and leaving the state in 2026. These firms will no longer need to buy allowances anymore if they won’t be selling gasoline in California (Phillips says they will be).

Now, like most people I believe that most of the gasoline from the closing refineries will need to be replaced from somewhere, probably from imported fuel. But I’m not sure if anyone knows exactly how that fuel will be imported, and by whom. Probably the importing firms themselves don’t know for sure. They probably aren’t going out and buying carbon allowances yet on the off chance they might be selling gasoline in California. In any event, the current compliance window runs through December 2027, so firms have almost two years to buy the allowances they need even for gasoline they sell today.

This scenario is one of a market disequilibrium, where previous buyers of permits have stopped buying, and the new buyers haven’t yet shown up at the auction. For whatever reason, firms in environmental compliance markets behave very myopically. Anecdotally, compliance entities prefer to “pay as they go” and buy allowances only when they need to surrender them for compliance. If this is what’s going on, we may see a big run up as we get closer to the compliance deadline in 2027.

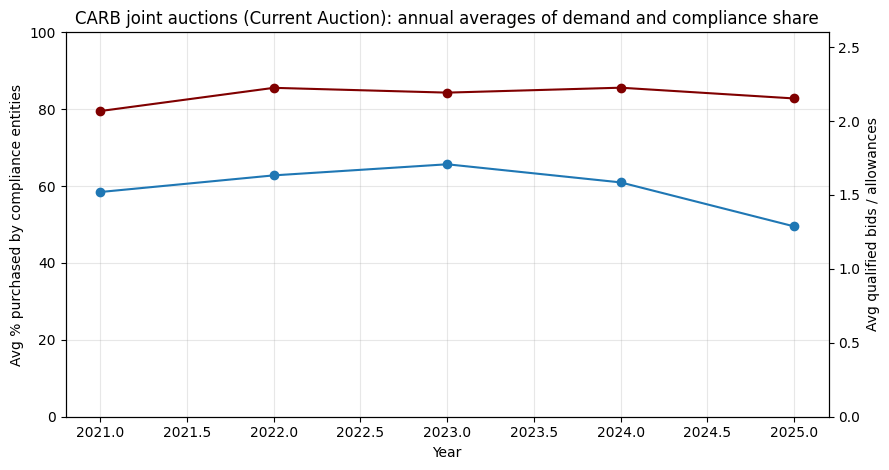

What data are available don’t really scream that this is what is going on. In the following figure I plotted a couple statistics that are reported from the CARB auctions. The top line is the percentage of purchased allowances bought by compliance entities (as opposed to financial firms with no emissions). There is no real movement in this number since 2021. The blue line plots the number of allowances sought (e.g. the quantity of allowance purchases bid) divided by the number being sold. A number greater than one means that there was more “demand” than supply. Demand was in fact a little lower in 2025, even after accounting for the fact that the number of allowances on offer was also declining each year.

Even if this is part of the story, it still doesn’t explain why other firms aren’t jumping on allowances today at what seem like discounted prices. There is clearly risk, but how high is it really? Is it really, more than Ghana level risk? Or Six Flags Corp. bond level risk? Sometimes markets just aren’t as efficient as economists think they should be.

The Energy Institute blog will be on vacation next week for the President’s day holiday. It will return on Monday, February 23.

Follow us on Bluesky, LinkedIn, and our new Instagram. Also subscribe to our email list to keep up with future content and announcements.

Suggested citation: Bushnell, James. “Why Are California Carbon Prices So Low?” Energy Institute Blog, February, 9, 2026, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2026/02/09/why-are-california-carbon-prices-so-low/