One day in January 1948, in Atlanta, Georgia, a little boy named David stood in line with his father to visit the Freedom Train, filled with original American documents such as the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Gettysburg Address.

As we wandered through the train, we looked at these seminal papers. Several times, my father pointed out the signatures of Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and, of course, George Washington.

Now, after having seen more noted American historical signatures on various documents, my great American Jewish moment occurred. Frequently, I ask myself, “Could I actually have seen that most famous George Washington letter to the ‘Hebrew congregation in Newport, Rhode Island,’ written after he visited the synagogue in 1790?”

However, why not? My father, Louis, read to me from the letter: “May the Children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the goodwill of the other inhabitants; while everyone shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.”

That letter has come to mean so much to me that I purchased two facsimiles and have read the letter many times.

As Presidents’ Day approaches (February 16), I would like to review its meaning.

Noted American Jewish historian Prof. Jonathan Sarna offers a very important interpretation of the meaning of this letter.

Rights for religious liberty

“A short exchange between President George Washington and the Jewish community of Newport articulated a theory of religious liberty grounded in inherent natural rights rather than toleration – even before the First Amendment was added to the American Constitution.”

Sarna, who has been a historical activist throughout his life, wanted to see the actual letter in 2011. It had disappeared.

In order to make the letter visible and also protected, a journalist of The Forward began to write about the lost letter. After a search which he initiated, since the name of the owner was known, the letter was found in a basement – unprotected.

Actually seeing the original of the letter has motivated me to study the analysis by Sarna and other scholars. When Sarna was in Jerusalem and spoke about the meaning of the letter, I was present.

I quote from Sarna’s words again. “The letter reframes American religious freedom as a lived constitutional principle forged through minority claims, not merely legal text.”

Now Sarna emphasizes a key point: “Discussions of America’s religious origins are often framed almost exclusively through Christianity, yet this letter suggests that even the nation’s most important founder rejected such a narrow understanding.

“Over time, the letter took on sacred proportions not only for Jews but for anyone who cared about religious liberty. In today’s climate, where debates about religion and America are increasingly shaped by Christian nationalism, the letter stands as a foundational proof text for pluralism.”

My personal experience with pluralism was most fascinating. During the last major American celebration, the Bicentennial in 1976, I was a rabbi in Wilmington, Delaware, before making aliyah the following year. I received information encouraging ministers, priests, and rabbis to plan “American celebratory events” to be funded by the Bicentennial Commission of the US. I applied, the synagogue received a grant, and the cantor and I wrote a “Pageant of Freedom” in song with an original text. Five hundred people – Jews and Christians – attended the event.

Let me introduce Irvin Ungar, the collector of the art of Arthur Szyk. Szyk had disappeared from the scene except for his famous Haggadah. Ungar discovered Szyk art treasures. A major article on Szyk appeared in The New York Times in December 2025.

Szyk moved to the US from England at the beginning of World War II. His art depicting the story of the US had a defining figure, George Washington.

In his award-winning book on Szyk, Arthur Szyk: Soldier in Art, Ungar demonstrates the particular interest of the artist in the freedom he understood was to be found in the US.

“Early on, he was drawn to George Washington and the concept of democracy. And he was mindful of the unique freedoms of American Jews precisely because the United States protects religious liberty and – for the most part – embraces the diversity that inspired its motto ‘E pluribus unum,’ [meaning] ‘Out of many, one.’”

In 1930, Szyk drew his first picture of George Washington, on a horse, leading the American colonist fighters. “This painting and 37 others in this series of Washington and the American Revolution,” Ungar notes in his book, “were completed by Szyk in time for the 200th anniversary of Washington’s birth in 1932.” Bought by the president of Poland, they were presented to President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a gift.

“When FDR delivered his famous ‘Four Freedoms’ speech to Congress in January 1941, the walls of the White House displayed the entire Szyk series.”

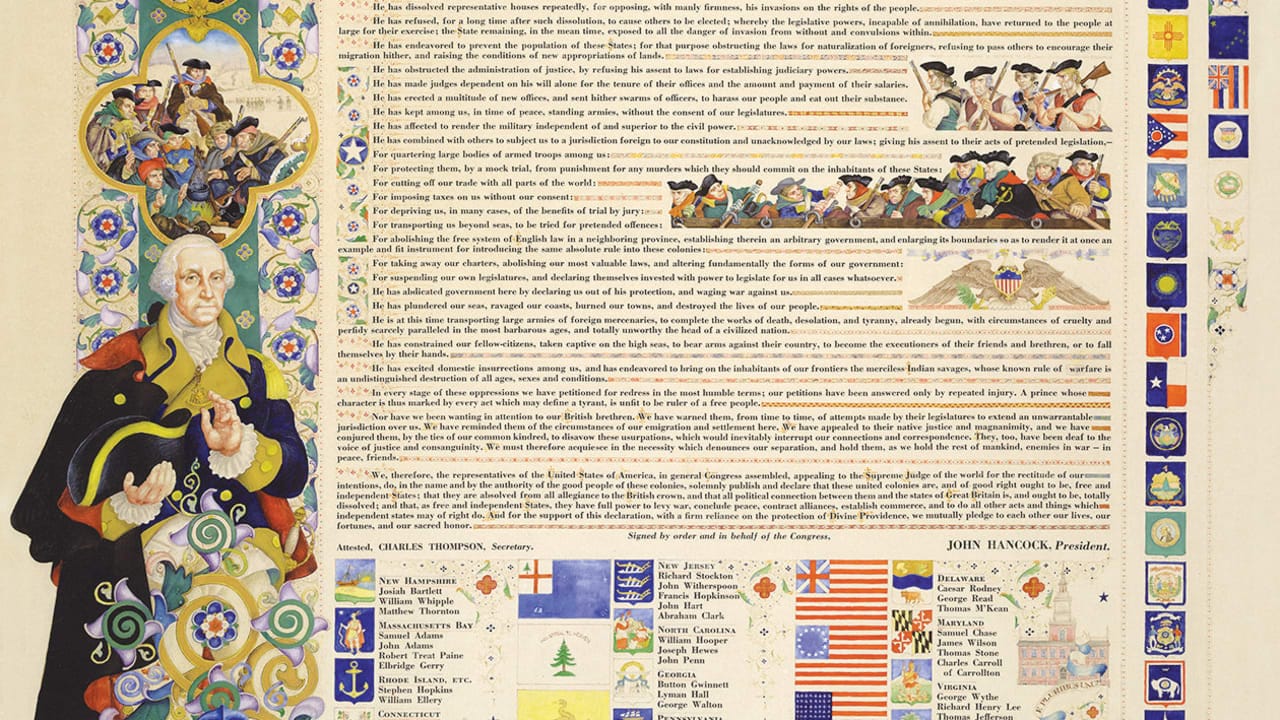

For another American historical moment, Ungar describes the drawing, by Szyk, of the Declaration of Independence in this fashion. “All the symbols of the American Revolution are present, most prominently George Washington with hand raised as if in benediction.”

“The text, beautified with color and pattern,” Ungar writes, “highlights the most important words: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Ungar points to the meaning of the 1790 letter. “Twenty-four years after these words were written, Washington made it clear in his letter to the Jews of Newport that those inalienable rights, or ‘inherent natural rights’ as he termed them, included religious liberty.”

Prof. Melvin I. Urofsky wrote the book A Genesis of Religious Freedom: The Story of the Jews of Newport, RI, and Touro Synagogue. He added in the book title “including Washington’s letter of 1790.”

As it happens in his book, facing the picture of noted benefactor Judah Touro, he writes: “Although this letter carries with it a unique and cherished significance, in many ways it is a treasure for the entire nation. America, as [Alexis] de Tocqueville famously wrote, had been ‘born free,’ unfettered by the religious and social bigotries of medieval Europe.”

This letter demonstrates “that the United States did not espouse mere toleration, but full liberty of conscience. Freedom of religion in the United States had risen to the level of an inherent natural right, protected by the Constitution and now part of those inalienable rights mentioned in the Declaration of Independence.”