If you’re a fan of the Cincinnati Reds baseball team, there are many ways you can follow the team’s fortunes.

You can check the scores. You can watch or listen to their games being broadcast.

If you’re a super-fan, though, you could subscribe to The Riverfront, a periodic online newsletter that takes its name from the location of the team’s stadium by the Ohio River. The most popular issue of The Riverfront remains its March 2021 takedown of the team’s owner: “Love the Reds. Boycott Bob Castellini.”

In second and third place: “Who will be the Next Reds Hall of Famer?” and “Which number should the Reds retire next?”

The author of The Riverfront clearly knows his stuff. He’s also a regular columnist about the Reds for Cincinnati Magazine and co-author of a book about the team’s history. Obviously he must be some sportswriter who has been hanging out in the locker room at the Great American Ballpark to get the latest insights, right?

Actually, the writer is a former prosecutor, former judge and former law school dean. He’s not even in Cincinnati. He’s more than 500 miles away in Richmond, where Chad Dotson is currently head of Virginia’s prison system. So how did Dotson become so interested in the Reds? Easy: He grew up in Wise County.

The nation’s sports map bears scant resemblance to other maps. Wise County may be in Virginia, and we may think that Virginia is oriented toward Washington-based sports teams. Part of Virginia certainly is, but there’s another part of Virginia whose sports allegiances are quite different. That part is Southwest Virginia (and perhaps much of Southside, too).

Many Reds fans come out of Southwest Virginia because the team’s radio network has long extended into Appalachia. You can hear the Reds on seven stations in West Virginia, mostly the western and southern part of the state. You can hear the Reds on two stations in Virginia, in Abingdon and Wise. You can even hear the Reds on two stations in Tennessee — one of those in the Bristol-Kingsport-Johnson City market.

By contrast, the Washington Nationals radio network extends only as far as Lynchburg and Martinsville.

I’ve often written columns to remind Virginians of all the ways our diverse state is connected — school funding in rural communities depends on the economic health of Northern Virginia, so any downturn there connected to federal cutbacks will be felt throughout the state.

I’ve also written columns to remind fellow Virginians of how different some parts of the state are — such as the column about how few of our statewide candidates have been to Lee County, our westernmost county, and what candidates could learn from visiting the state’s southwestern corner even if they don’t find many votes there.

This is one of those.

On Saturday, Major League Baseball will send two of its teams to play a regular-season game at the Bristol Motor Speedway. The racetrack — “The Last Great Colosseum,” some call it — is 8 miles into Tennessee, but it’s still in the Bristol market and part of that Bristol market is in Virginia, so this game is close enough for us to care about, not because of what it means athletically but what it signifies culturally.

An aerial view of the field at the Bristol Motor Speedway. Courtesy of Major League Baseball.

An aerial view of the field at the Bristol Motor Speedway. Courtesy of Major League Baseball.

This game is part of a nine-year series of “specialty games” that Major League Baseball has staged at locations other than its usual stadiums since 2016. Five of those have been at Williamsport, Pennsylvania, site of the Little League World Series. Others have been at Omaha, Nebraska, in conjunction with the College World Series; at Dyersville, Iowa, to honor the movie “Field of Dreams;” at Birmingham, Alabama, to honor the old Negro Leagues (the Birmingham Black Barons were a famous team); at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, to honor service members. This is sort of baseball’s equivalent to the National Hockey League’s Winter Classic where it holds a game outside (which some hard-core hockey fans will tell you is the true spirit of the frozen sport).

The two teams that will take the field (one specially prepared by the famed Roanoke Valley-based groundskeeper Murray Cook) in Bristol on Saturday night weren’t chosen at random. They are the Atlanta Braves and the Cincinnati Reds, two teams that used broadcasting to stretch their fan base. The Reds will be the home team on Saturday. Officially, that’s because the Reds are giving up a home game for this one; the first two games of the three-game series with the Braves will be in Cincinnati. Unofficially, though, the Reds are the home team because, culturally and historically speaking, they are.

The Reds’ radio network has long extended into Southwest Virginia, long enough for Dotson to have grown up listening to the team. Before the Braves moved from Milwaukee to Atlanta for the 1965 season, there were no Major League teams in the South, which left the South open to marketing for other teams. By many fan accounts, the Reds and the St. Louis Cardinals were the teams that did the most to fill that void. In 1976, Ted Turner both bought the Braves and launched the TBS “superstation.” One outgrowth of that: Braves games were broadcast nationwide, the first pro sports teams whose games were available so widely. That helped build a national fan base, but especially so in the South. To this day, you can still pick up Braves games on Roanoke radio — but not Washington Nationals games.

Vivid Seats, the ticket-selling agency, has produced maps that show which team is the favorite in each county in the country, based on who’s buying tickets to what. That naturally skews toward the nearest teams geographically — if you’re a Seattle Mariners fan in Virginia, you’re probably not buying tickets to their home games, you’re buying tickets to a road game. By that standard, the map may more accurately reflect which stadiums people are most likely to visit, rather than the home team. Still, the map shows the Cincinnati Reds reach into Southwest Virginia while the Atlanta Braves dominate (with some exceptions) as far north as Bath County. Among those exceptions: Vivid Seats customers in Floyd County (which admittedly might be a small sample size) buy more tickets to Pittsburgh Pirates games than any other. Interest in going to Washington Nationals games runs pretty thin once you get south of Charlottesville.

It’s not just baseball. The Vivid Seats map for football is much the same. The Washington Commanders dominate as far as Wythe County. Across most of Southwest Virginia and much of Southside, the top team is the Charlotte-based Carolina Panthers. A few exceptions pop up: In Scott County we see the Cincinnati influence again, because the Cincinnati Bengals are tops there.

This is more than just about sports. This is about how we see ourselves. It’s natural that the more northern parts of the state look toward Washington. (I grew up in the Shenandoah Valley, where most of the television channels available in the pre-cable, pre-satellite era were out of D.C.) Our fellow Virginians should understand that there are some of us in the southern part of the state who look elsewhere for sports allegiances. It’s not simply that we root for different teams, it’s that we see ourselves differently — because we are different.

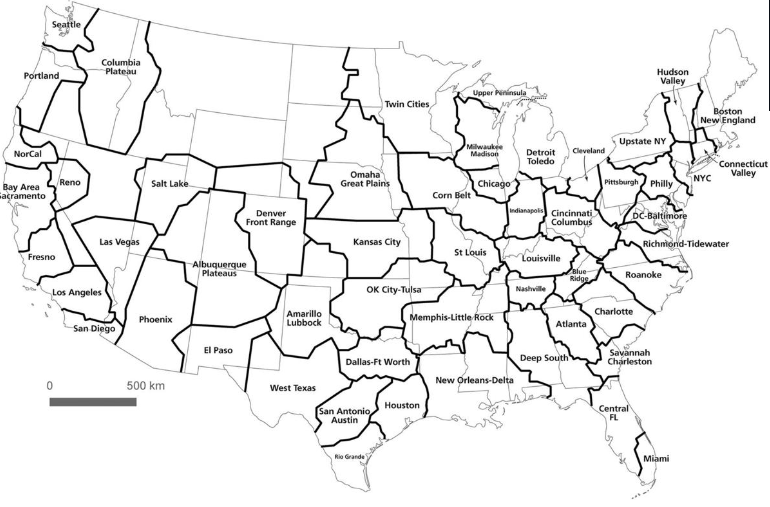

In 2016, two geographers drew a map of the U.S. economy based on commuting patterns. They found that Virginia was divided into five different economies: four big ones plus a piece of Tazewell County that’s tied to West Virginia around Bluefield. Their map shows Southwest Virginia more economically oriented toward Tennessee, with the Roanoke Valley and New River Valley more connected with North Carolina than we are with the rest of our own state. (Wytheville is roughly the dividing line).

Here’s what the United States would look like if its states were redrawn along economic lines. Courtesy of “An Economic Geography of the United States.”

Here’s what the United States would look like if its states were redrawn along economic lines. Courtesy of “An Economic Geography of the United States.”

There are policy implications to all this. By necessity, we pass laws on a statewide basis, but our economy isn’t shaped for a one-size-fits-all solution. If our next governor doesn’t understand this, she will soon enough. Perhaps that’s a reason why all the statewide candidates should take Saturday night off and go attend a baseball game in Tennessee — and while they’re in the neighborhood, they could also go visit Lee County, some of them for the first time.

See where gubernatorial candidates Winsome Earle-Sears and Abigail Spanberger stand on energy issues in our Voter Guide. Want more politics? Sign up for West of the Capital, our weekly political newsletter:

Related stories