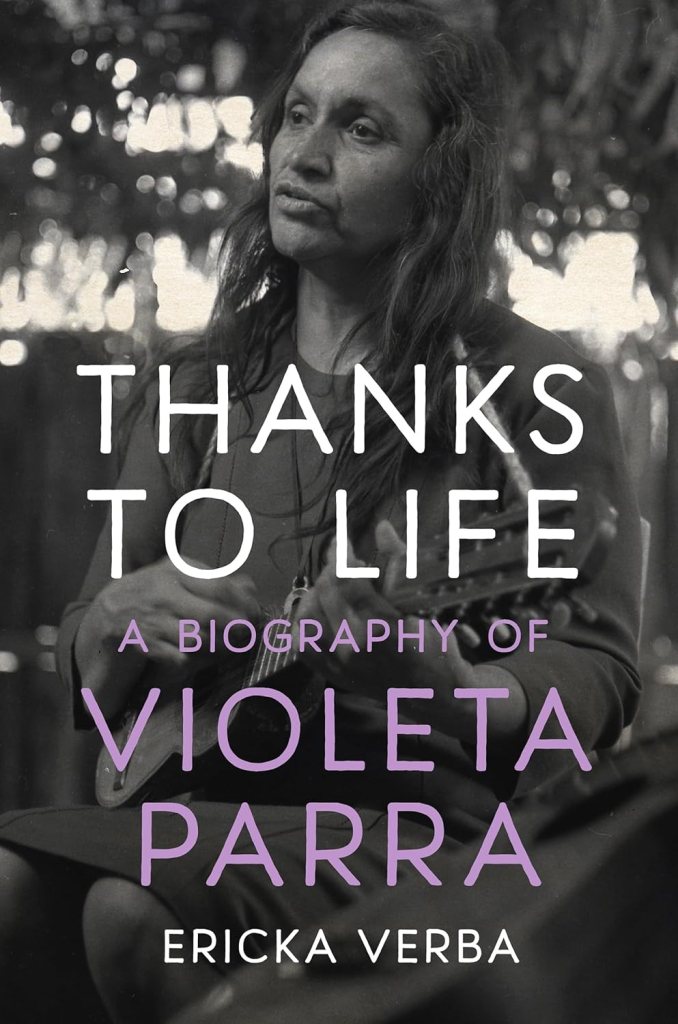

Most of what I’ve learned about Chile has come from reading novels by Chilean writers, studying the country’s political fortunes since the 1973 overthrow of Salvador Allende’s government, and the long dictatorial reign of Augusto Pinochet. I knew little about Chile’s artistic heritage, so when Ericka Verba’s biography of Violeta Parra reached me I was eager to read it. I had never heard of Parra.

Violeta Parra grew up in a large impoverished family. Her father was a music teacher and her mother hailed from the agrarian class. In class conscious and stratified Chile, Parra’s origins couldn’t have been more humble. This fact was very much a double-edged knife, on one hand allowing Parra to project an authentic voice of the people or pueblo, but on the other contributing to Parra’s being exoticized or dismissed as primitive by “sophisticated” academics and art curators.

Verba paints a well-rounded portrait of Parra, first and foremost as an artist — a musician to begin with — and later as a painter, maker of tapestries and sculptures, who by dint of timing, talent and sheer will, became the first Latin American to have a solo show at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris. Housed in the Louvre Palace, this exhibition was visited by a host of dignitaries and the brightest stars of the expatriate Latin American artistic community. A little more than three years after this triumph, Parra took her own life with a single gun shot to the temple. By then she was struggling with debt, poverty, and a variety of physical and psychological concerns. Only after her death did the Chilean public really embrace her and come to appreciate her life and body of work.

Parra made her mark as a folklorista, which in itself was remarkable as she had no formal training in ethnography or music, and in fact never learned to read or write music. But this didn’t stop her from traveling thousands of miles, from one end of Chile to the other, interviewing hundreds of people along the way. She collected songs, stories, poems and began performing them. On the strength of her ability to interpret and embody this material, Parra toured all over Europe, though her most fruitful ground was Paris where there was a large, vibrant contingent of Latin America artists.

An artist through and through, Parra never stopped creating. She scrounged materials or enlisted whatever was to hand, and used her bed as a workspace. Her resourcefulness was boundless. As Verba describes her, Parra was an everything-ist. Over the course of her eventful life, which included two marriages and other romantic liaisons, and the raising of children and grandchildren, Parra was a barroom singer, a folklorista, a modern composer, painter, sculptor, and tapestry-maker. Her personality was protean and volcanic. Short in stature, dark-skinned, and — by her own admission — physically unattractive, she nonetheless refused to take a backseat to anyone. Mercurial, demanding, frequently rude and occasionally violent, Parra never shed her class consciousness. As a result, many of her songs became protest anthems against the Pinochet dictatorship. Parra stood with the oppressed, both in Chile and beyond.

What comes across so emphatically in this finely researched biography is Violeta Parra’s obsessive determination to live her life as a creative artist. The mark she made will not be erased.

This review originally appeared in the California Review of Books.