Critic’s Picks: Exhibitions of the Summer

4 Columns

A quartet of art recommendations, spanning both sides of the Atlantic.

NO-PHOTO 2025, installation view. Both posters captioned “Photo: Hatem Khaled, Khan Younis, 19 May 2025.” Courtesy NO-PHOTO.

For this week’s missive, we present a bouquet of critic’s picks for the exhibitions of the summer, taking us on an expansive road trip of the mind through Arles, France; London, England; and New York City.

• • •

NO-PHOTO 2025, at Les Rencontres de la Photographie 2025, Arles, France, through October 5, 2025

Reviewed by Aruna D’Souza

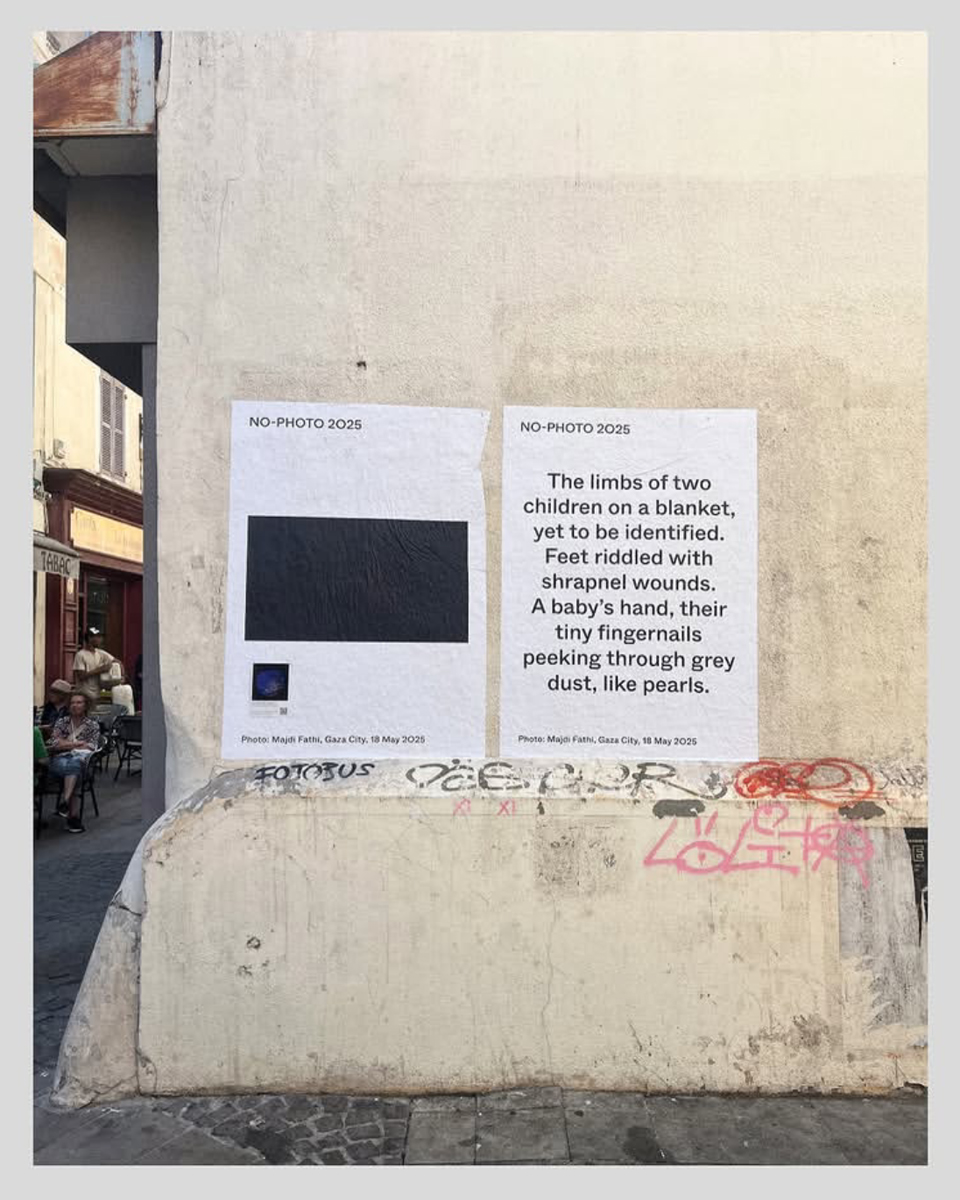

NO-PHOTO 2025, installation view. Both posters captioned “Photo: Majdi Fathi, Gaza City, 18 May 2025.” Courtesy NO-PHOTO.

The theme of this year’s Les Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles, “Disobedient Images,” nods toward defiance, refusal, and rule-breaking. However, the most pressing issue of our time—Israel’s genocide in Gaza—is practically invisible across the festival’s forty-two exhibitions. (One exception among the hundreds of works on display: Adam Rouhana’s two-minute film Blood Memories.) This almost complete absence raises the inevitable question: how to curate disobedience if you’re unwilling to break the rule of silence about Palestine?

It took two extramural interventions to bring Palestine squarely into view. One was Nan Goldin’s opening night presentation, which she ended with a short film and an impassioned speech decrying genocide. The other is the work of NO-PHOTO, who describe themselves as “a group of activists and artists who refuse to accept political aesthetics without political responsibility.” The collective pasted poster diptychs on walls around town: one sheet shows a black rectangle representing a redacted photograph, including the name of the Palestinian photographer who took it, and the other a verbal description of said image hovering between ekphrasis and poetry. “A baby’s hand, their tiny fingernails peeking through grey dust, like pearls,” reads part of one.

NO-PHOTO’s gesture cuts through the institutional muteness. It also raises crucial questions about our consumption of these images of violence. When Sontag wrote “Regarding the Torture of Others” in 2004, highlighting the troubling eroticism that underpinned the Abu Ghraib photographs, she rightly asked us to consider the line between witnessing and devouring. It feels slightly—but not entirely—different now, when Palestinian testimony has been almost entirely left out of mainstream media’s accounts of the razing of Gaza, especially, as Ariella Aïsha Azoulay has observed, in the context of Israel’s weaponization of photography to manufacture consent for their actions. NO-PHOTO’s project allows for Palestinian voices to be heard while resisting the fetishization of suffering. It also insists on the power of art—here, poetry—to make history visceral, even if it’s not visible.

• • •

Tai Shani: The Spell or The Dream, Somerset House, Strand, London, through September 14, 2025

Reviewed by Emily LaBarge

Tai Shani, The Spell or The Dream, 2025 (detail). Courtesy Somerset House. © David Parry, PA Media Assignments.

Full disclosure: I contributed to The Spell or The Dream, a major new commission by the Turner Prize–winning British artist Tai Shani. Over seventy participants—including Anne Boyer, Brian Eno, Cecilia Vicuña, Eileen Myles, Lola Olufemi, Maxine Peake, Yanis Varoufakis, Tanya Tagaq, and The Palestinian Sound Archive—have offered readings, playlists, archival radio plays and broadcasts, audiobooks, and conversations around the theme of dreaming. Dreaming of a different future; dreaming as an escape from, or even a dismantling of, capitalism; dreaming as world-building; dreaming as enacting radical politics; dreaming as a way to survive grief and loss.

From August 8 to September 14, you’ll be able to tune in 24-7 to The Dream Radio. In fact, if you want to catch every dreaming voice, you’ll have to: no slot will be repeated—the dreams are fleeting, fantastical, immaterial, urgent. These disembodied voices that literally course nonstop through the air accompany Shani’s first public art piece in the UK, which has been installed at the center of the vast, cobblestoned Somerset House quadrangle.

An enormous, androgynous mixed-media figure of fair features and flowing blue locks lies housed in an angular, futuristic-looking coffin—or is it a display case—or is it a capsule crashed to earth from outer space, like Superman did, who never made it home again. The slender giant slumbers, their chest visibly rising and falling due to the wonder of animatronics, as the sun rises and sets, again and again, and the dream radio transmits a collective of lives and imaginations, pasts, presents, and futures, as if this unearthly visitor were an emanating host. They channel the channel that we need to hear but so often cannot, for all the surrounding noise.

• • •

Diane Arbus: Constellation, curated by Matthieu Humery, Park Avenue Armory, Wade Thompson Drill Hall, 643 Park Avenue, New York City, through August 17, 2025

Reviewed by Margaret Sundell

Diane Arbus: Constellation, installation view. Courtesy Park Avenue Armory. Photo: Nicholas Knight.

Diane Arbus’s images may embody types—nudist, sex worker, circus performer—but they transcend the limits of categorization through an accretion of photographic details that reveal the irreducible singularity of each sitter. It is always this nudist, this sex worker, this circus performer—and none other. If Arbus’s eye seems clinical, it is also all-accepting. Therein lies the humanity that pushes her pictures onto a razor’s edge between voyeurism and love. Diane Arbus: Constellation gives viewers the chance to walk that fine line more than four-hundred-and-fifty times in the largest display of Arbus’s oeuvre to date, including pieces never before publicly shown, all printed by her former student Neil Selkirk—the only photographer authorized by the artist’s estate to work with her negatives.

For Arbus lovers—or anyone interested in plumbing the depths of our species’s strangeness—this is a tremendous opportunity. There is so much here to see: the small boy with clenched face and big feet, a toy grenade in his outstretched hand; the naked middle-aged couple sitting in their living room, flanking a tchotchke-topped television, beaming at the camera like sunlight; the bewigged and be-feathered trans woman at a drag ball staring stoically off into the distance while her partner slumps on her chest; the identical twins with matching dresses and mismatched stockings and almost matching faces. All await the viewer’s delectation. The installation—salon-style groupings arrayed on metal lattices scattered throughout the Park Avenue Armory’s cavernous Drill Hall—encourages the gaze to wander, as does the sheer number of images assembled. Give into this drift, and let the strength of Arbus’s photos arrest your attention again and again.

• • •

LIFE—a group show, curated by Arnold J. Kemp, Artists Space, 11 Cortlandt Alley, New York City, through August 16, 2025

Reviewed by Alex Kitnick

LIFE—a group show, installation view. Courtesy Artists Space. Photo: Carter Seddon. Pictured, far left, on wall: Christopher Garrett, “A LINE OF FLUID BLUE IS JUST THERE” (after Etel Adnan), 2015. Far right, on floor: Nayland Blake, Rafts, 2019.

In 1975, twenty-three-year-old impresario Jeffrey Deitch presented Lives: Artists Who Deal With Peoples’ Lives (Including Their Own) As The Subject And/Or The Medium of Their Work at 105 Hudson Street, then known as the Fine Arts Building, in New York. Fifty years later and five blocks to the east, multi-hyphenate Arnold J. Kemp is staging LIFE—a group show at Artists Space, which trims Deitch’s title but maintains a similar spirit. How to fit the sprawling diversity of LIFE into the two hundred and fifty words I’m allotted here? At a June 5 performance, Gregg Bordowitz offered a near-abecedarium of fifteen terms—activism, alprazolam, art, betrayal, censorship, complacency, complicity, critical theory, eschatology, faith, improvisation, illness, independence, institutional critique, Marxism, mendacity, mortality, museum, negation, practice, program, service, structural determinism, study, testimony, volition, vulnerability, witness—riffing on each for two minutes. In the gallery, Nayland Blake offers a single vocable, delivering candles shaped to form the word LOVE in partially melted red, white, and blue wax. The effect is both mournful and hopeful, matching the show’s many affects and media.

“The big mess of having a life,” a grave-rubbed frottage by Christopher Garrett reads, quoting poet Etel Adnan, and poetry might be one skeleton key here: a zine of verse edited by Kemp with contributions by Erica Hunt, John Keene, and others sits on a shelf free for the taking. Correspondence is crucial, too. In a vitrine by the entrance, one finds letters sent to Geoffrey Hendricks from Pope.L, the late performance artist whose life and work touched many of the show’s contributors. That both of these artists—the former a progenitor of Fluxus and the latter a protean figure who reanimated its legacy—have passed, in 2018 and 2023, respectively, also seems pertinent. A contemporary exhibition cast in the shape of a makeshift memorial, LIFE is largely about what comes after life. The writer Robert Glück captures the ethos best with a brick-painted ceramic lingam dedicated to the New York painter Martin Wong (1946–99). Rest in power.

A quartet of art recommendations, spanning both sides of the Atlantic.