A LOT has changed in the Australian beef industry in the past 25 years.

From the introduction of the National Livestock Identification System and the widespread implementation of Meat Standards Australia to the adoption of genomics, producers have faced both challenges and opportunities.

While many of these changes have been visible in day-to-day operations, it is equally important to recognise that the herd itself has changed, with the cows of 2025 genetically very different to those of a quarter of a century ago.

An analysis of genetic improvement conducted by the Animal Genetics and Breeding Unit (AGBU) in Armidale was presented at the recent Association for the Advancement of Animal Breeding and Genetics (AAABG) conference in New Zealand.

The study, by Rob Banks, Daniel Brown, Katrina Moore, Brad Walmsley and Andrew Swan, estimates that since 2000, genetic improvement has added more than $11.3 billion in additional value to the beef industry, roughly equivalent to one year’s current entire gross value of beef production.

The research used BreedPlan genetic trend data for several southern and northern breed groups. The southern breeds included Angus, Hereford, Charolais, Wagyu, Shorthorn, Murray Grey, Simmental, South Devon, Red Angus, Limousin and Speckle Park. The northern breeds included Brahman, Droughtmaster, Belmont Red, Brangus and Santa Gertrudis.

For each breed, the analysis focused on the current breed $Indexes, measures of economic value that combine EBVs for multiple traits, such as growth, fertility, mature cow weight, carcase yield, meat quality and maternal ability. Each trait is weighted according to its effect on profitability in a defined production system and market.

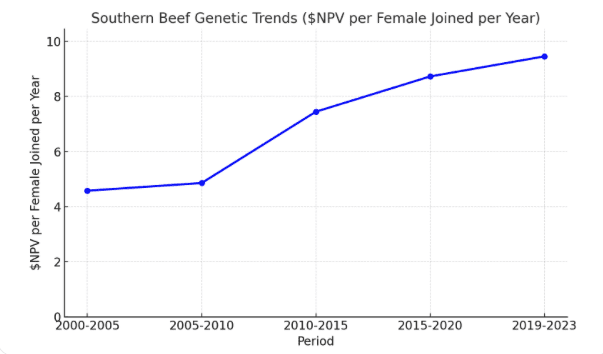

Breed trends were averaged within each region (southern and northern) and weighted by the number of registered animals each year to give an overall figure for each group. The analysis then calculated the average annual change in $Index value per female joined for 5-year periods between 2000 and 2023, using 2000 as the baseline year.

To estimate total industry impact, the gain per female joined was multiplied by:

The estimated number of bulls entering the industry annually (based on male calf registrations and a proportion assumed to be used as sires).

The average number of females joined to each bull over his lifetime (100 in their model).

This produced an industry-wide net present value (NPV) for each calf drop, expressed in today’s dollars, and showed the accumulated value of genetic improvement since 2000.

For southern breeds, the average rate of gain rose from $4.58 per female joined per year in 2000–05 to $9.46 in 2019–23. This means that, within the production and market assumptions built into the index, the average female joined in 2019–23 is genetically capable of generating $9.46 more profit per year than the 2000-drop equivalent. Over a 4-5 year productive life, this equates to an extra $38–$47 per cow from genetic gain, before accounting for management or seasonal effects.

Gains both north and south

While improvements were greatest among the southern breeds, the northern breeds also recorded gains. The index for northern breeds increased from $0.75 to $0.83 over the same period, with a steady upward trend in fertility, particularly for the Days to Calving EBV.

These figures are industry averages across all recorded herds in each group, not the realised gain in every herd. Herds sourcing sires from above-average herds can exceed these rates of progress, while others may perform below the average.

The analysis also showed a clear lift in the rate of genetic gain from around 2015 onwards.

According to AGBU, a major factor was the rollout of single-step genomic prediction across major breeds between 2016 and 2018, enabling genomic, pedigree and performance data to be combined in a single evaluation.

The researchers also note that average index accuracy has been rising, implying that more and/or better recording practices are being adopted. This increase in accuracy has been accompanied by a steady rise in the number of animals entering genetic evaluation each year, broadening the population under selection and strengthening the evaluation process.

Together, these developments have supported a faster rate of genetic progress across the industry.

Based on the data presented by AGBU, if today’s herds had the genetic merit of the 2000 herd, average returns would be lower and cost of production higher. It is also important to note that the $11.3 billion figure is an industry-level estimate. It assumes that the genetic progress measured in recorded herds has flowed through to the commercial herd in line with the model’s sire usage and joining assumptions.

At the farm level, realised gains depend heavily on bull buying decisions. Sourcing sires from herds making above-average progress can lift a herd ahead of the industry average.

Buying below-average sires will slow progress or even see herds fall behind. The past 25 years of change show that genetics can make a measurable difference, but only if those gains are actively brought into the herd.

Alastair Rayner

Alastair Rayner is Principal of RaynerAg and an Extension & Engagement Consultant with the Agricultural Business Research Institute (ABRI). He has over 28 years’ experience advising beef producers and graziers across Australia. Alastair can be contacted here or through his website: www.raynerag.com.au