The history of the internet offers some examples. Take the Russian social media/blogging platform LiveJournal. When it was popular in the mid-2000s, English-speaking users knew it as a space for young people to share their feelings or geek out about Harry Potter. But if you’re a Russian speaker, you probably know LiveJournal very differently – as an important site of public intellectualism and political discourse, playing a rare role in hosting voices from the opposition.

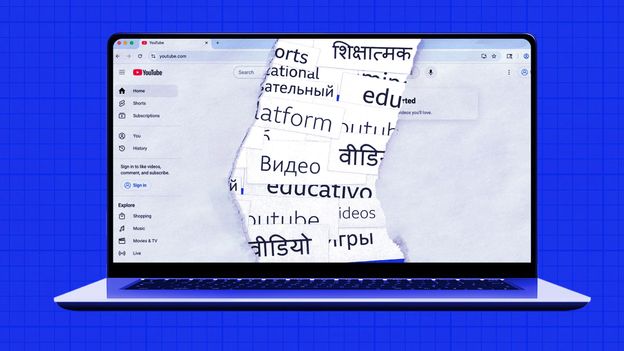

With the biggest technology companies based in the US, a cultural blind spot has emerged where we often assume that the English internet is representative of the rest of the world. Research about YouTube in particular has a significant English-speaking bias – typically written in English, published in English-speaking countries and focused on English-language videos.

The internet’s leading platforms are more difficult to study than you might think. Computers can blaze through text, but video is harder to parse at scale. Platforms like YouTube, the world’s most popular video service, don’t offer tools to create the large representative samples necessary to understand the platform as a whole, or big swaths of it like linguistic communities.

As a result, YouTube is often understood through the easily accessible tip of the iceberg: its most popular videos. Between the language bias and this popularity bias, when users, creators, academics, educators, parents, teachers and even policymakers talk about platforms like YouTube, we’re typically just talking about the part that’s most visible to us – a small, unrepresentative piece of it. (For more, read Thomas Germain’s story The hidden world beneath the shadows of YouTube’s algorithm.)

So, how do you study what’s under the surface? A couple years ago, we came up with a way to do what YouTube’s tools couldn’t: we randomly guessed the URLs of videos – more than 18 trillion times – until we had enough videos to paint a picture of what’s really happening on YouTube.