Executive Summary

Rising physician shortages in the United States, in tandem with restrictive state-level scope-of-practice (SOP) laws that often unnecessarily restrict the practice authority of non-physician practitioners (NPPs), have contributed to an inefficient health care workforce and suboptimal access to quality and cost-effective care for patients.

While SOP laws nominally promote safety by restricting the types of care NPPs can provide – and often require them to render their services under the supervision of a physician – NPP providers with full practice authority have demonstrated meaningful improvements to the health care system, including in access, cost, and quality, particularly in rural and underserved communities.

Encouraging nationwide reforms, possibly through federal guidance or interstate collaboration, to provider SOP laws and promoting NPP practice authority may both mitigate physician shortages and produce favorable patient and workforce outcomes in the U.S. health care system.

Introduction

The U.S. health care system depends on a wide array of medical professionals to deliver and support comprehensive care for patients. These providers have strict guidelines dictating their role in practicing medicine, governed by state medical boards that consider various levels of education, training, and practical experience required for licensure. These restrictions are broadly defined as scope of practice (SOP). SOP varies widely depending on the type of provider and their state of licensure, as each state enacts unique laws that guide medical authority. States ultimately determine SOP laws to ensure standards of care and safety for their population, but increasingly, also to optimize workforce efficiency in underserved communities.

Despite extensive evidence on the benefits of expanded SOP for underutilized providers, many states throughout the country prohibit non-physician practitioners (NPPs) from assuming full practice authority. In recent years, rising shortages in many areas of the health care workforce have forced policymakers and other stakeholders across the United States to reevaluate how provider SOP is determined, finding that such restrictions often exacerbate these shortages beyond what safety standards require.

NPPs are medical professionals who play a central role in treating and managing patients throughout the health care system. As their name implies, NPPs are medical personnel that have graduate medical education, but are not medical doctors or osteopathic doctors. This class of professionals includes nurse practitioners (NPs), physician associates (PAs), certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs), and pharmacists. In some instances, NPPs are allowed full practice authority (FPA), allowing these providers to independently exercise the full extent of their clinical knowledge. In other cases, NPPs provide care in collaboration with or under the supervision of a licensed doctor. Evidence indicates that expanded SOP can significantly improve access to medical services and offer potential cost-savings, all while maintaining high quality of care.

Several policy options may address provider inefficiencies in the health care system, including a uniform expansion of SOP for select NPPs and promoting educational opportunities that encourage more participation in the health care workforce. A review of current licensure status, the effectiveness of NPP-led care, and the applicability of scope of practice regulations is necessary to ensure that patients have access to needed high-quality care now, as well as considering future health care needs.

The health care services sector has been among the fastest growing industries in terms of aggregate employment over the past three decades. Today, health care professions – including physicians and non-physician practitioners – account for about 13 percent of all non-farm employees in the United States, up from around 7.5 percent in 1990. This growth has far outpaced that of many other notable sectors, such as manufacturing and retail. As of last year, health care practices were the largest employers in 38 states, supporting a total national workforce of more than 17 million individuals. This figure includes more than 900,000 professionally active physicians and over 4 million nurses, the majority of whom practiced direct patient care.

Federal policymakers and other stakeholders anticipate the sector to continue growing in scale and influence, as household and national health expenditures are forecasted to represent a greater overall share of economic activity in the immediate future.

Physicians

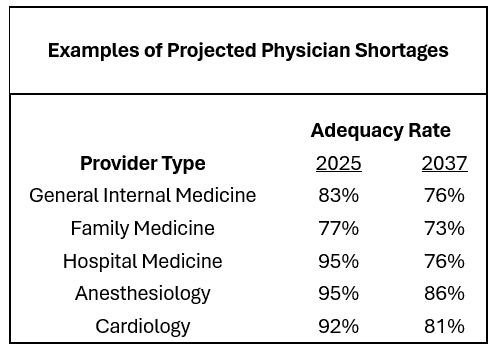

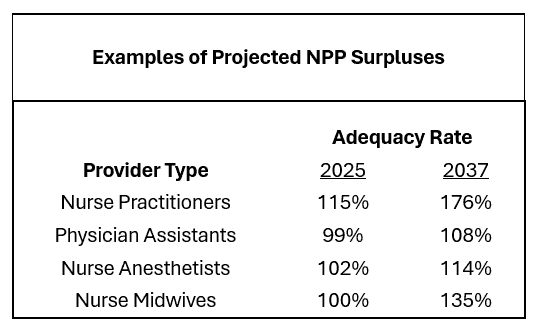

Despite steady overall workforce growth, the United States is currently experiencing a well-documented and worsening shortage of physicians. According to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), these shortfalls may total 190,000 full-time equivalent doctors across myriad specialties by the year 2037, disproportionately impacting states with large rural populations. For instance, HRSA projects that the total supply of primary care physicians will fail to meet demand by more than 87,000 professionals; rural areas will only be able to support 58 percent of the expected need for services. This problem may be more pronounced in specialized disciplines, especially in surgical fields, where expected national shortages may be as high as 36 percent. Although these estimates account for more than a decade of predicted patterns, the threat to practices around the country is immediate, with 23,000 physicians anticipated to exit the workforce permanently by the end of next year.

Physician shortages underscore a dual-sided challenge relating to both the supply and demand of the workforce. Although there are many factors that may contribute to an imbalance between these two sides of the equation, policymakers and other stakeholders have continually suggested that age-demographic shifts, worsening health, and challenges facing the physician pipeline as the most consequential trends.

Demand-side Trends

On one side, the demand for services has accelerated rapidly in recent years due to an aging population and declining health status. A key driver of this trend is the rising utilization of health care services among older adults, particularly Medicare beneficiaries. Since 2011, health care utilization has surged as a growing proportion of the total U.S. population has enrolled in Medicare. Generally, this demographic is more likely to be diagnosed with one or more chronic conditions, necessitating more frequent visits with health care professionals. Over the next decade, this age group is projected to grow from just under 19 percent of the total population to over 22 percent. Additionally, a heightening prevalence of chronic conditions among younger age groups has also increased demand for physicians. Despite enormous clinical advancements in chronic condition prevention and management, the age-adjusted rates of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and other illnesses in the U.S. population have increased or remained steady over time. Multi-morbidity has also become more common in recent years, affecting roughly half of the total U.S. population. This chronic disease burden is expected to worsen, with the number of adult individuals affected expected to double by 2050.

Supply-side Trends

On the other side of the issue, physician shortages are constrained by both external demand and endogenous challenges. For example, the prospect of becoming a licensed physician may be viewed as a less attractive option for many aspiring health care professionals, as doctors continually report burnout from tedious administrative tasks and poor work-life balance. While physicians are generally paid more than non-physician practitioners for the same type of work, the added benefits may not offset perceived quality-of-life and educational barriers to entry. Compounding this problem is a scarcity of educational and training infrastructure for prospective medical students. Although medical school programs have accepted a record-high number of applicants, many qualified candidates are turned away due to either staffing shortages, an insufficient number of seats, or both. Moreover, the process of training these newly enrolled students requires an already overburdened physician workforce to limit time spent in clinical practice, further contributing to health care access problems. Last, while the number of licensed physicians has increased year-over-year, there remain issues in adequately distributing these providers across all areas of the country. Rural hospitals and office practices have continually cited challenges of recruiting, supporting, and retaining new physicians, largely due to uncompetitive wages and cultural differences.

Non-physician Practitioners

As the physician workforce continues to lag far behind patient demand, non-physician practitioners and advanced practice providers present a more promising outlook. In the health care system today, NPPs represent over 40 percent of the clinical workforce, contributing across a range of settings from primary care to surgical teams. At the forefront of this shift are nurse practitioners (NPs), who have become increasingly prominent in hospitals and outpatient practices nationwide. Several other practitioners, such as physician associates (PAs), certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs), and certified nurse midwives (CNMs), have also observed substantial growth. Although these providers have traditionally been viewed as only supporting roles to physicians, NPPs are trained to perform many of the same clinical functions as their physician counterparts. Recognizing the potential to bolster efficiency and fill provider gaps left by physician shortages, many states have revised NPP scope of practice restrictions to expand their roles and promote health care access.

As a result, the number of employed NPPs has grown considerably in recent years, a trend that is expected to continue as physician adequacy rates across the country decline. According to HRSA estimates, several NPP professions are projected to face workforce surpluses under current SOP laws, as the supply of qualified providers is anticipated to exceed the demand for services they are currently authorized to deliver. This growth may be particularly felt in rural areas, as NPPs are more likely than physicians to serve in Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs).

Comparability of NPP-led Care to Physician Care

Despite concerns about safety, a growing body of research indicates that when NPPs are permitted full practice authority, the quality of care delivered is comparable to services furnished by physicians. In addition to the analogous standard of care, NPP-led services in many settings have been associated with enhanced cost-effectiveness, as workforce resources are utilized more adeptly, access to care increases, and downstream health status improves.

Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), which include NPs among several other nursing specialties, have a well-established collection of literature supporting the quality and safety of care provided under full practice authority. This is especially evident in primary care, where NPs are allowed to diagnose, treat, manage, and prescribe medications for patients with chronic illnesses. A 2023 review, which included seven studies of NP-led primary care clinics, concluded that NP providers offered a comparable standard of care for people with multiple chronic diseases, with additional notable cost-savings, compared to physicians. Many of these findings are supported by a separate study looking at patient outcomes and satisfaction in ambulatory care settings. A trial that randomly assigned patients to either an NP or physician with the same level of practice authority observed no discernable differences in overall health status, with patients under NP-led care even exhibiting slightly lower diastolic blood pressure. Though patient satisfaction varied moderately in favor of physician-led care, data showed NP-led care resulting in comparable levels of care utilization.

Another review published last year found numerous benefits associated with NPP-led care for patients in acute care settings, such as intensive care units and emergency departments. The studies included, though modest in sample size, demonstrate the same safety and quality of care delivered by NPPs in diagnosing, treating, and managing patients with more severe injuries and illnesses. Moreover, the implementation of NPPs in acute care facilities, with various levels of practice authority, resulted in overall shortened lengths of stay and waiting times for patients receiving care from all types of providers.

CRNAs, who are trained to prepare patients for surgery and administer anesthesia, have similarly proved value when given full practice authority. An article published in Health Affairs found that patients who received care from CRNAs with full practice authority did not observe any significant differences in mortality or complications risks when compared to treatment administered by an anesthesiology physician. The authors also suggested that CRNAs with full practice authority could help free up physicians’ time and improve health outcomes by independently managing lower-risk cases, allowing anesthesiologists to focus on more complex patients. The study cited in a separate article stipulated that CRNAs could safely manage many of the same high-risk cases typically handled by anesthesiologists.

Often overlooked as non-physician practitioners, pharmacists play an essential role in managing short-term and long-term care for patients with myriad health care needs. Evidence suggests that pharmacists can improve access to care and potentially lower costs for patients when given the opportunity to absorb many physician responsibilities, including routine medical tests and screenings. This expanded role, which could help alleviate physician shortages, has not observed meaningful impact on pharmacists’ work hours or ability to conduct other responsibilities. Pharmacists’ prescribing authority – which includes the ability to modify prescription medications – is of particular importance, as these treatments are often time-sensitive and require crucial communication with patients. Research shows pharmacists with full prescribing authority have not compromised patient safety, nor led to overprescribing. Moreover, granting pharmacists the ability to prescribe and dispense medications has been proven to increase access to care and help mitigate the spread of infectious diseases.

Considering the current literature on the effectiveness of care delivered by many non-physician practitioners and advanced practice providers, states may find merit in reforming NPP SOP laws to enhance their roles in an increasingly splintered health care workforce. Expanding SOP, as evident in numerous cases, can increase access to care and promote more favorable health status outcomes, especially in drastically underserved and rural communities.

Current Landscape of Scope of Practice Laws

Scope of practice laws dictate the clinical tasks and responsibilities that licensed health care providers, including both physicians and non-physicians, are legally authorized to perform for patients. These laws are designed to ensure that health care providers deliver care within the bounds of their training, education, and practical experience. While the intent of these laws is to safeguard patients’ safety, the boundaries between provider roles can be open to subjective and politicized interpretation and frequently fall behind evolving clinical competencies and workforce needs. Perhaps unsurprising, a lack of consensus among state legislatures, professional medical boards, and advocacy groups has led SOP laws to vary significantly across the United States , contributing to ongoing confusion about the roles and capabilities of medical professionals and further underutilization of qualified providers.

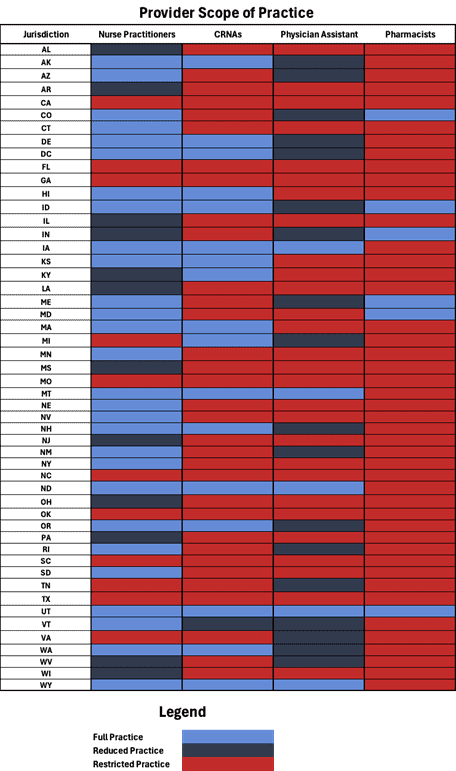

SOP laws can broadly be categorized under three levels of practice authority: full, reduced, and restricted. In some states, NPs and PAs operate under “full practice authority,” allowing them to evaluate patients, diagnose conditions, and initiate treatments independently. Conversely, other states mandate physician supervision or collaborative agreements, limiting NPPs’ autonomy and potentially restricting access to care in areas with physician shortages. Examining the level of practice authority across several NPP types in each state (see table below) reveals a great deal of variability in SOP laws. This is especially true for NPs, with 27 states permitting FPA for primary care services and prescribing autonomy, and the remaining 23 states requiring at least some level of limitations for the same types of care. Meanwhile, CRNAs, PAs, and pharmacists vary moderately in practice authority but are generally categorized as restricted, despite exhibiting comparable effectiveness standards as NPs and physicians for their respective services. Taking note of these inconsistencies, it appears that addressing nationwide workforce issues may prove difficult without more interstate cooperation.

Sources: National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP), and author’s interpretations

Barriers to Expanding Scope of Practice

Expanding SOP for NPPs faces a complex web of federal and state-level barriers. These barriers affect provider autonomy, workforce flexibility, and access to care, especially in rural and other underserved areas of the country.

A large barrier to expanding SOP is some of the licensure requirements themselves. Most states mandate that NPs and PAs work under the supervision of a physician, often with restrictions on how many NPPs a single physician may oversee. These supervisory rules constrain the flexibility of care teams, particularly in areas where physicians are in short supply. Even when physicians are willing to collaborate, the administrative burden and legal liability associated with supervision agreements can disincentivize these partnerships. As a result, qualified PAs may be underutilized or excluded from clinical settings that could benefit from their services.

Even in states that have adopted full practice authority, some impose “transition to practice” requirements, requiring newly licensed NPPs to complete 1,000 to 4,000 hours of supervised clinical work before achieving full independence. Although well-intentioned as a patient safety measure, these requirements can serve as barriers to entry, especially in communities with limited access to supervising physicians or employers willing to support the transition period. In some cases, NPs must even pay supervising physicians for oversight during their transition, adding financial burdens to new practitioners.

Governance structures also play a role. In many states, medical boards – often dominated by physicians – set rules that may further restrict non-physician practice beyond what statutes require. These boards can serve as gatekeepers, slowing or blocking reforms despite evidence of safe and effective care provided by advanced practice providers. This dynamic is compounded by strong opposition from professional physician organizations, which often argue that SOP expansion could compromise patient safety, despite growing evidence to the contrary. Physician organizations have expressed concerns that expanding NPPs’ SOP could compromise patient safety due to differences in training and clinical experience between physicians and NPPs. These organizations advocate for physician-led care models, emphasizing the extensive education and training physicians undergo.

The lack of uniform national SOP frameworks further complicates matters. This discrepancy can disincentivize health care facilities from employing NPPs to their full capacity, thereby limiting the potential benefits of expanded SOP and creating inconsistencies that hinder interstate practice, telehealth expansion, and efficient workforce deployment. For example, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) grants full practice authority to NPs within its health system. This federal leadership is important, though unique, as other federal health care settings may still enforce restrictive supervisory requirements.

Beyond regulatory and financial hurdles, institutional cultures and practices may resist changes that empower NPPs. Concerns about role delineation, professional hierarchies, and traditional care models can hinder the integration of NPPs into broader health care delivery systems.

Policy Options to Expand Scope of Practice

Expanding SOP for NPPs represents a pragmatic approach to improving health care access and efficiency. Last year, the United States collectively enacted more than 120 bills pertaining to provider scope of practice. Many of these laws attempt to address physician shortages by broadening NPP roles in the workforce, especially in primary care and behavioral health settings. This legislative trend has continued into 2025, highlighted by Arkansas’ landmark decision to grant full practice and prescriptive authority for CNMs. Policymakers have several viable strategies to encourage such expansion.

One prominent policy option involves the establishment of standardized national guidelines for NPPs’ scope of practice. Currently, significant variability exists between states, creating inefficiencies and barriers to interstate practice. By developing uniform federal recommendations or model legislation, policymakers could offer states clear benchmarks and facilitate broader adoption of expanded practice roles. Federal agencies, such as the Department of Health and Human Services, could incentivize adherence to these guidelines through conditional funding mechanisms, much like Medicaid waivers or allowable federal matching rates, for states implementing expanded NPP roles. It should be noted that this can be achieved either through standardizing SOP as it is – even at a restrictive level – or through national adoption of FPA.

Moreover, reducing regulatory and bureaucratic barriers through legislative reform at the state level is essential. Policymakers could remove unnecessary requirements such as collaborative agreements or physician oversight for routine practices, enabling NPPs to utilize their full training effectively. Streamlining licensure procedures and supporting interstate compacts can further facilitate NPP mobility, helping to address workforce shortages swiftly, especially in rural and underserved communities. NPPs are more likely than physicians to serve in HPSAs, and states with full practice authority for NPs have been shown to have more equitable provider distribution and shorter wait times.

Investment in interprofessional education and collaborative practice models is another essential policy lever. Federal and state educational funding can prioritize curricula that train health care providers collaboratively, breaking down traditional professional silos. By embedding a culture of mutual respect and teamwork early in health care professionals’ education, policymakers can facilitate smoother integration and acceptance of expanded NPP roles within health care teams.

Additionally, demonstration projects and pilot programs can play a pivotal role in promoting SOP expansion. Initiatives conducted under the CMS Innovation Center, for example, could empirically demonstrate the safety, quality, and cost-effectiveness of expanded NPP practices. Data from these pilots can directly address opposition concerns, inform future policy development, and provide tangible evidence supporting broader legislative action. For example, a 2016 study in Health Policy found that states granting greater prescribing authority to PAs and NPs experienced reductions in outpatient care costs ranging from 11.8 percent to 16 percent.

Finally, policymakers can enhance public education and awareness campaigns to address misconceptions about the quality and safety of care delivered by NPPs. By communicating evidence-based benefits and highlighting the crucial roles that NPPs play, particularly in underserved and rural communities, policymakers can garner broader public support for legislative reforms.

Collectively, these policy strategies offer comprehensive pathways for overcoming existing barriers and unlocking the full potential of non-physician health care providers.

Examples of Current FPA in Health Care

As more states consider reforms to scope of practice, it is important to learn from situations where FPA is already working, particularly in instances addressing rising health care needs.

Impact of Telehealth and COVID-19 on Accelerating Scope of Practice Reform

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a catalyst for rapid transformation in health care delivery, particularly through the expansion of telehealth and reform of SOP restrictions. In response to the public health emergency, federal and state governments temporarily waived or modified long-standing regulations to maximize the capacity of the health care workforce. These temporary flexibilities demonstrated the potential benefits of broader SOP authority and helped lay the groundwork for permanent reforms in several states.

One of the most significant changes during the pandemic was the expansion of telehealth access. To meet surging demand, many states removed requirements for in-person physician supervision, allowing NPs, PAs, and other non-physician providers to independently deliver virtual care. In states such as , governors issued executive orders granting NPs full practice authority during the emergency, which was later codified into law. Similarly, states including Alabama and Michigan took steps to ease supervision requirements for PAs, improving access to care amid workforce shortages.

The pandemic also demonstrated the efficacy of non-physician-led care models. Published research, such as the above, found that NPs and PAs delivered high-quality care comparable to physicians, even in independent or virtual settings. This evidence helped shift public and policymaker attitudes toward a more flexible, team-based approach to care delivery.

While many temporary waivers expired with the end of the public health emergency, the experience reshaped the policy landscape. As of 2025, at least six states have enacted permanent SOP expansions influenced directly by pandemic-era waivers. These reforms reflect a growing recognition that outdated restrictions can undermine access, especially in rural and underserved communities. The pandemic thus proved to be an inflection point, accelerating the movement toward more modern and equitable scope of practice laws.

Nurse Practitioners in the Department of Veterans Affairs

Since 2017, the VA has officially granted FPA to APRNs – including NPs, CNMs, and Clinical Nurse Specialists – working within Veterans Health Administration facilities. Under this policy, appropriately credentialed APRNs are recognized as licensed independent practitioners, enabling them to evaluate patients, diagnose conditions, order and interpret diagnostic tests, initiate and manage treatments, and prescribe medications, all without mandated physician supervision.

A final rule issued by the VA in 2016 extended this direct-access model specifically to veterans, allowing APRNs in VA settings to practice to the full extent of their training across nearly all practice areas, excluding the prescription of some controlled substances, which remains governed by the Controlled Substances Act.

Studies have documented positive impacts in facilities that embraced this model. A found that a 10-percent increase in clinics staffed with privileged primary care NPs correlated with an approximate 4-percent reduction in wait times for new patient appointments – about 0.3 fewer days – while wait times for existing patients also decreased. This evidence suggests that FPA for NPs contributes to more efficient care delivery and improved access for veterans.

Under this model, APRNs are required to complete standard VA credentialing processes, including meeting state licensure and facility-level competency standards. Once privileged, NPs function similarly to physicians within their scope, an approach that has helped the VA address provider shortages and reduce wait times, often in rural or high-demand areas.

Conclusion

Provider scope of practice laws enacted across the United States have long contributed to significant health care workforce inefficiencies, limiting access to quality and cost-effective care. As physician shortages are expected to worsen into the next decade due to an increasingly sick and aging population, rising demand for health care may lead policymakers to consider expanding workforce roles of NPPs.

A review on the effectiveness of several NPPs demonstrates meaningful improvements in the health care system’s performance, including enhanced access to care, notable cost-savings, and a high quality of care. The benefits associated with NPP-led care may be exceptionally beneficial in rural parts of the country, where health care provider shortage areas are more prevalent.

Encouraging nationwide adoption of enhanced SOP reforms, including full practice authority, for several NPP providers may mitigate the scale of physician shortages and produce favorable patient and workforce outcomes in the U.S. health care system.