We count everything. Calories, steps, heart rate, minutes of REM sleep, books we’ve read, books we plan to read, series we’ve watched and series that are waiting to be watched, trips taken and those yet to take, close and not-so-close friends, movies… We gain peace and tranquility every time we put a number to an act. The more chaos reigns around us, the more addicted we become to numbers. Order, metrics and law are the mandates of technomoralism, its norms determined by a single god: technology.

Such statistics seem more trustworthy than intuition, feelings or perceptions of reality as delivered by our five senses. James Nicholas Gilmore, professor of media and technological studies at Clemson University in South Carolina, believes that of our own volition, we have entered a spiral that he and his colleagues refer to as the “process of datafication”. It entails converting all of life into data, as he explains by email. “At first, only tech enthusiasts signed up for it, but it has achieved generalized acceptance and today, many see datafication as being attractive and exciting, and able to generate supposedly useful information about how we eat, move and live,” he writes.

Around 2010, constant self-monitoring was a practice limited to nerds who identified with the self-quantified movement. Its objective was to reach the peak of self-knowledge through numbers. But 15 years later, being a “self-tracker” has not just become normalized, numbers have taken on a moral and motivational tone. How are you going to become “the best version of yourself” if you don’t have control of your metrics? How do you expect to “optimize your performance” without quantifying your goals?

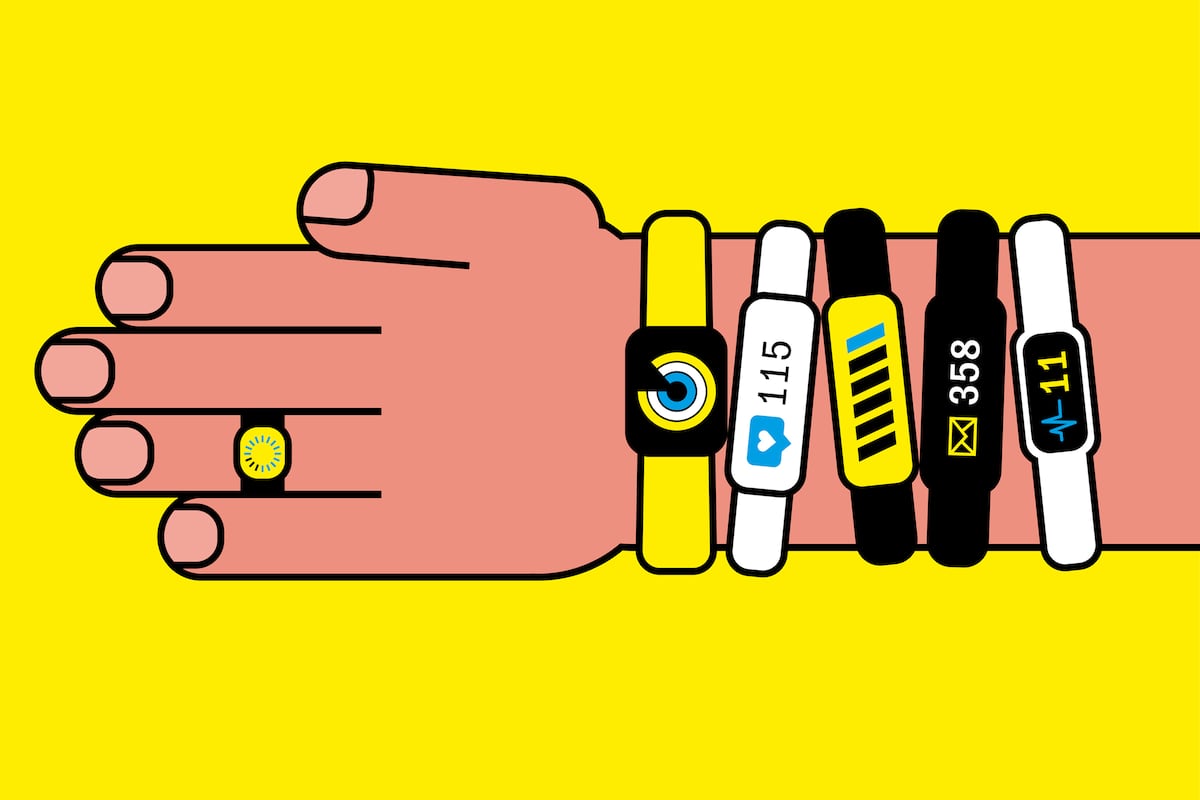

In 2023, the global exercise tracking device industry was valued at around $56.7 billion and it shows no signs of slowing. Fitbit bracelets, Garmin watches, Apple glasses and Oura rings promise to objectify health and wellness, and even achieve something as ambitious as “the complete optimization of existence.” In recent times, we’ve formed such an emotional link to these devices that we rarely, if ever, question their functioning. We think they know us better than we do ourselves, and we trust their measuring systems because they offer us — we think — a more objective view than our own malleable and tainted perspective. If these devices, which we obligingly call “wearables,” as directed by their creators, break down and begin to display erroneous data — for example, heartrates approaching cadaver levels — we become overwhelmed, as reported by several studies. It matters little that the body has sent nary a signal of imminent death, because in data we trust. Our faith in these devices is unwavering.

The numbers they offer are the result of combining biometrics with automatic learning techniques that generates notes on a person’s activity. Can we trust these measurements? Gilmore says it depends on the user. “FitBit recognizes steps through a combination of sensors and an algorithm that processes the data. If you walk at a normal rhythm, the device will register your steps accurately, but if you use a cane, it’s possible that it won’t register your movements. Nor do the oxygen sensors on wearables work well on dark skin.”

What they are adept at is giving us a feeling of control. “For many people, numbers bring objectivity to their lives, and that brings them mental peace,” says Gilmore. “People seem to have fun with metrics in all aspects of their life,” writes Deborah Lutton, one of the great researchers of the self-quantified movement, by email. “That’s why they also document their consumption of culture. It helps them to position themselves as avid readers, or as people with refined musical tastes. This kind of quantification has always been done, before with paper, pencil or spreadsheets, and now with apps and platforms that help us to share our metrics with the world.”

Social validation is the latest twist on our habit of self-monitoring. A decade ago, it was enough to merely show off our best metrics, but nowadays, we want to compete with them, — and win. “We don’t just register our advances for ourselves, we archive them so that others, possibly many others, usually strangers, can admire what we have achieved. The social component is very powerful,” observes Karen Shackleford, a social psychologist who specializes in media and technology. “Social success is, after basic survival, the greatest human desire,” writes Matthew Lieberman, author of Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect. Various studies have demonstrated that, when they’re given the choice, people prefer a compliment to a dessert or even sex. “We love it when others validate us,” Liberman says.

The desire to be liked (and to like ourselves) leads us to lie. People will say they’ve read 50 books in a month or devoured six seasons of a series over a single weekend. It makes no difference if they merely scanned the text, watched the series at double-speed, or that they’re not able to remember anything about either. “Social interaction implies pressure,” says Shackleford. “It could be that we enjoy less because we are worn out by telling and posting, it could be that we even read a book that doesn’t interest us because it leads to social reward, and surely, we will read faster to be among the first to add a new edition to our list.”

Controlling every act in our lives is useful in the pursuit of intellectualization. Gary Wolf, one of the founders of the self-quantified movement, likes to say in his presentations that “numbers remove emotional resonance from problems and make them intellectually manageable.” Emotions are a nuisance and can disrupt the actions and performance of a person who is “focused on optimization.” “Perhaps it’s an exaggeration to speak of the fetishization of data,” says Professor Gilmore, who is the author of the book Bringers of Order: Wearable Technologies and the Manufacturing of Everyday Life. “But I think that many people are overly happy to join dataist ideology, the belief that data leads to truth and that more data is always better. We have to understand that data can also be fabricated, that it is a construct, sometimes well-made and precise, but that it is always a representation of what is achieved through computational processes. It’s not the absolute truth.”

An individual obsessed with metrics is, according to Korean-German philosopher Byung-Chul Han, an achievement-subject. Productivity reaches into every aspect of their life, from sleep to nutrition, from reading to leisure. Constant self-monitoring stimulates two areas: introspection and the desire for self-exploration. Its advances are objective and measurable because, according to technomoralism, that which is not measured does not exist. Such a thought might get us into trouble.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition