Our study investigated whether public versus private segment could influence oral reading fluency indicators during elementary school. The assessment was conducted approximately two years after the start of the COVID-19 outbreak. The data generation process for these indicators was assisted by AI, including the following outcomes: WRCM as a speed measure, PCW as an accuracy measure, and the SBS as another speed latency measure. These fluency reading indicators have been used more frequently in previous investigations6,31, in particular WRCM and PCW. In addition, we also generated data on the average CCW, which we assumed as an indicator of prosody since it provides insights into the rhythm and expression of correct oral reading. For instance, prosody often involves grouping words into meaningful phrases and pausing appropriately between these phrases. Monitoring the average number of CCW read can help identify points at which students pause or encounter difficulties in maintaining the flow of speech, which may reflect challenges in navigating phrase boundaries related to prosody. We analyzed the performance in these four indicators across different grade levels, specifically from the 2nd to the 5th level of elementary school, observing that the private school segment outperformed the public school segment in WRCM in the 4th grade and in the PCW in the 3rd grade. No differences were found between school segments regarding the SBS and the CCW.

A previous study conducted in Brazil with a broader age range sample (6th to the 9th year of elementary school) demonstrated significant differences between public and private schools, particularly in the 7th grade, where private schools outperformed public schools in terms of WRCM6. Another study, with a more similar age range of Brazilian participants (10 to 11 years old), also found that private school students outperformed their public school counterparts in WRCM32. However, our findings of such differences occurring in earlier grades, such as the 4th grade, have not been consistently observed, as most studies have focused on older children. We also observed that private students are already reaching 5th-grade levels regarding the WRCM during the 4th grade, and this maturation effect is not evident within public schools. Furthermore, our findings indicated that children from private schools performed better in the PCW compared with public school students even earlier, such as during the 3rd grade. Similar early emerging gaps have been documented in other transparent orthographies. In Italy, a large survey reported an 86-point gap between high- and low-socioeconomic background children in the 4th grade on an international reading scale33. Comparable inequalities are already visible in Spanish, as Cubilla-Bonnetier et al. examined 2nd–3rd graders in Panama and found that the private-school group read almost three times faster and made significantly fewer errors than their public-school peers34.

This suggests that differences between public and private schools regarding reading fluency may emerge during the early stages of elementary school. Notably, the transition from the 3rd to the 5th grade is recognized as a crucial period marked by a shift towards the utilization of the lexical route, as opposed to the phonological route prominent in earlier years31. The lexical route involves the direct recognition of familiar words as whole units, relying on the reader’s stored mental lexicon, which contains a mental representation of words. Although we did not find differences in 2nd-grade performances between public and private students, potentially related to the phonological route, we cannot rule out the possibility that certain everyday practices and activities in schools might influence reading fluency performance in subsequent years. Evidence suggests that the quality and frequency of reading practices experienced in the first two years of elementary school can significantly impact a student’s level of reading fluency at the end of the 3rd year35. Thus, these early experiences can be decisive factors in the years that follow in the educational process.

As mentioned earlier, evidence suggests that private schools outperform public schools in terms of teacher attendance2, lower student dropout rates3, and potentially in the frequency and quality of reading activities during the early school years. These factors could be associated with the disparities in the performance of oral reading fluency. However, another factor that could be associated with our findings is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Families with higher socioeconomic status may have had better resources to adapt to remote learning, including access to technology, a conducive home environment, and parental support. In contrast, students from lower-income families may have faced additional hurdles, such as limited access to online resources, a lack of quiet study spaces, and potential challenges in receiving adequate parental guidance due to various socio-economic stressors. In situations where resources are scarce and parental support is limited, learning from home may exacerbate educational disparities, further widening the gap in children’s progress. In schools, children benefit from interactions with peers and supportive adults, opportunities that may be lacking for young children whose parents face pre-existing economic hardships36. As the effects of the pandemic have lessened and its impact becomes clearer, it will be important to track its effects on education37. Understanding and addressing these family disparities during the post-pandemic era is crucial for developing effective strategies to minimize the impact of the pandemic on educational equity and outcomes.

Even though statistically significant differences were not found in all cases across grade levels, the mean scores consistently show a trend favoring private school students in most variables, except for SBS, where public school students tend to make shorter pauses. We cannot rule out the possibility that these shorter pauses in public school students reflect greater automatization of the reading process. However, the consistent overall underperformance of these students compared to their private school peers also suggests the possibility of omitting key prosodic markers.

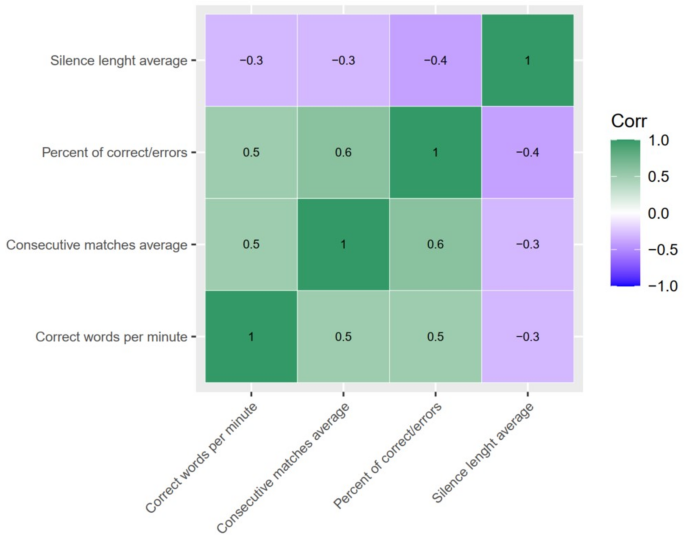

Another relevant finding, beyond the group comparisons, is the observed correlation between WRCM, CCW, and PCW. These indicators of oral reading speed and accuracy are expected to improve together as reading skills develop. Greater fluency is typically associated with shorter pause durations between sentences, which we also observed through the negative correlations with SBS, without implying a loss of prosody. In this context, studies such as Miller and Schwanenflugel38 have shown that as students become more fluent readers, they reduce the processing time needed between sentences. On the contrary, less skilled readers tend to pause more frequently and for longer durations, disrupting the natural flow of reading. Additional studies in more transparent languages have also found that word reading fluency and syntactic knowledge are significantly related to the development of prosody in fifth-grade students, contributing to improvements in expression, phrasing, and the reduction of inappropriate pauses39.

It is worth observing that the performance of public school students slightly declined from 2nd to 3rd grade, particularly in the CCW measure. A potential explanation for this may be a cohort-specific effect related to exposure to COVID-19 school shutdowns. In Brazil, children assessed in grade 3 during 2022 had begun grade 1 in 2020, precisely when public schools were closed for the longest period and remote learning was incipient. In contrast, the 2022 2nd grade cohort started school in 2021, after many systems had resumed hybrid or in-person instruction. A study conducted in Brazil suggests that early-primary cohorts affected by the 2020 school closures experienced the greatest unfinished learning in reading, with this effect potentially being more pronounced in the public system than in the private one40.

We utilized AI to assist in generating reading fluency data, demonstrating its potential for large-scale application by increasing efficiency, sample size, and statistical power. AI-assisted tools offer significant advantages for assessing oral reading fluency, particularly in time savings, scalability, and the ability to conduct test–retest screenings more frequently. Traditional reading assessments rely on manual scoring and data entry, often requiring hours to complete, while AI tools can evaluate an entire class in less than 20 min, reducing both time and subjectivity in the assessment process. Crucially, these efficiency gains do not compromise accuracy, as validation studies show correlations of 0.96 between fully automated scores and expert human ratings in both U.S. and Ghanaian elementary samples20,22. This level of agreement exceeds the typical inter-rater reliability reported for human scorers, confirming the robustness of AI-based scoring. This scalability allows entire grades to be assessed multiple times per year, enabling more precise monitoring of children’s reading progress and difficulties. These advantages are supported by a previous large-scale, multi-site study that processed over 100 h of children’s speech using AI-assisted automated extraction of fluency features, reporting this approach as scalable, automated, and cost-effective41. Future longitudinal studies using AI-assisted tools for reading fluency assessment may reveal additional sources of data variability that could be integrated into educational intervention programs.

An important limitation of our study is its cross-sectional design, with the absence of data from the pre-pandemic era. Although we speculate that the pandemic may have exacerbated the public–private educational gap, previous studies in Brazil have already documented that private school students perform better than public school students in aspects of reading fluency, and these studies6,32 were published before the COVID-19 outbreak. To be noted, however, is evidence showing that male students experienced significantly more reading fluency loss during a 24-week COVID-19 school closure42. Another important limitation is the absence of individual socioeconomic covariates and sex specification. Although previous research demonstrates that school-level factors can influence literacy achievement independently of family socioeconomic status43, and that teacher characteristics alone can explain nearly 10% of the variability in students’ academic achievement44, we cannot fully disentangle home and school contributions in the present data. Future studies should adopt a multilevel design that pairs the AI-based fluency task with detailed family-background data. Another limitation refers to differences in sample sizes between public and private segment, since we have a higher sample size in the private school segment. However, data collection took place between August and November 2022, when the COVID-19 pandemic was still disrupting Brazil’s public-school system far more than the private one. Municipal and state decrees often allowed private schools to resume in-person classes months before public schools45. Additionally, to run the AI-based reading task each school had to provide a quiet room with at least one networked computer. A national survey in Brazil performed in 2022 shows that while 91% of private elementary/secondary schools had computers available for student use, only 58% of public schools met this requirement46. Moreover, obtaining institutional consent and scheduling whole-class recordings proved markedly slower in the public sector, where many schools were still operating on hybrid timetables. This difference in sample sizes can affect the generalizability and statistical power of the study. However, in our statistical approach we included individual schools as a random-effect variable in the models, which potentially mitigated this limitation. In this sense, although we estimated the sample size, it should be noted as a limitation that the previous study used for this calculation involved 9th-grade students, while our study focused on students from 2nd to 5th grade, which may affect the precision of the estimation. Despite these limitations, the primary strengths of our investigation are multiple schools from different regions contributing data, and the innovative method of data acquisition using AI.

In conclusion, this study identified significant differences in reading fluency between public and private school students, specifically during the 3rd and 4th grades of elementary school. While our research focused on Brazilian students, similar difference in reading fluency between public and private schools have been reported in other countries30,47,48,49. The COVID-19 pandemic may have further widened these gaps, as disparities in access to technology and educational resources became more pronounced. Although the data were gathered in 2022, recent national and international monitoring confirms that reading proficiency has not rebounded to pre-pandemic levels50,51. Our findings therefore offer a critical baseline for evaluating the impact of subsequent recovery initiatives. To minimize these differences, intervention programs require an accurate and efficient method to assess reading fluency indicators.