A sudden workplace accident. A rear-end collision. A hard fall on the basketball court.

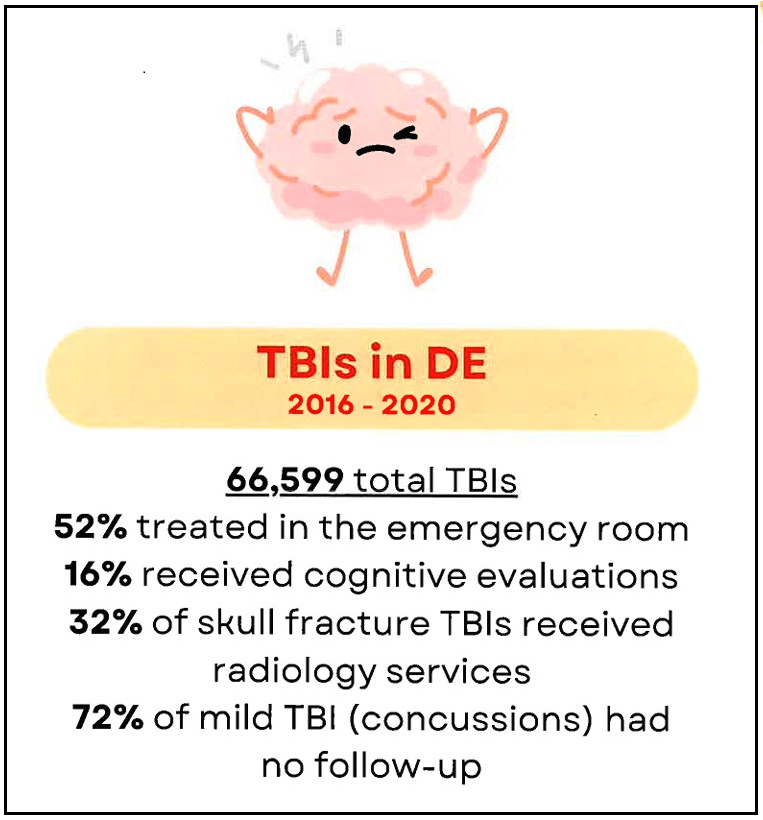

Nearly 7,000 Delawareans a year arrive at the emergency room with the headaches, nausea and blurred vision that are signs of a traumatic brain injury (TBI) — a blanket term covering anything from a simple concussion to a fractured skull.

For most of those people, that single visit to the emergency room is the only treatment they ever received in Delaware.

“We’ve heard from several folks that there’s not a lot of resources here in Delaware for TBI patients to find the follow-up care they need,” said Stefanie Lancaster, chairperson of the State Council for Persons with Disabilities’ Brain Injury Committee. “People have to go upstate or out of state to receive some of these services, some of these therapies that are up and coming.”

Healthcare professionals know that TBIs are often complex cases, with varying symptoms, unpredictable recovery paths, and the potential for significant effects that can pop up immediately or years after the initial trauma. (Few understand this better than Lancaster, who walked away from a catastrophic car accident with a TBI years ago, and today works with her disability to educate other Delawareans in similar circumstances.)

As any parent with a young athlete knows — these are injuries to keep a close eye on.

State Council for Persons with Disabilities

State Council for Persons with Disabilities

But when the council launched a study to track follow-up care, they found that 89% of Delawareans diagnosed with an “unspecified TBI” in the emergency room never sought follow-up care. What’s more, they were able to see what types of people were least likely to return for a second visit — employed workers in their 20s and 30s in Kent County, and older folks all over the state who rely on public transportation.

All of the findings came from a unique mix of insurance claims and clinical data held by the Delaware Health Information Network (DHIN).

Launched in 2007, DHIN was the first live, statewide health information exchange in the nation, working to address the state’s needs for timely, reliable and relevant health care information. Today, DHIN is connected to every one of the state’s acute‑care hospitals, long‑term care and skilled nursing facilities, and nearly every ordering provider, funneling more than 14 million clinical results annually into a community record spanning about 3 million patients nationwide.

Today, that clinical data is being supplemented by the voluminous documentation — diagnoses, procedures, medications, costs — that is required to process insurance claims.

The Delaware Health Care Claims Database contains claims records for 991,300 unique persons, representing more than 60% of Delaware residents, including Delaware Medicare, Medicaid, and several commercial plans with data spanning 2013-2025 — all anonymized to protect the privacy of individual patients.

Dr. Gurpreet Kaur had not worked with claims data before joining DHIN as a clinical analyst but quickly became enamored by what it can do.

“Linking both clinical and claims, that brings all together a new picture,” Gurpreet said. “Claims data tells you what actually happened to a patient — from diagnosis to treatment to outcome. Combining both of them and utilizing both the databases, we can support state agencies, non-state agencies, and other programs with information and recommendations about the affordability, accessibility and availability of health care.”

Clinical data — drawn from detailed patient records including diagnoses, lab results, vital signs, chart notes, imaging scans, etc. — has long been a gold standard of data-driven health research, but it can be difficult to collect and code.

Medical claims data offers three key advantages over clinical data, including:

It’s more complete — partially because of the sheer number of records created for insurance purposes, but also because insurance follows the patient at every stage of treatment — from clinic to general practice to specialists to therapy. “Even if they change insurance, even if they change their doctor or health care plan, as long as they are within the reporting area, we can track them,” Dr. Kaur said.

It’s very data-system friendly. Thanks to all of the codes that are used in the insurance industry, it’s easy to drill down to specific diagnoses or treatment options, and the data linked to billing addresses connects patient sets to census tracks.

It’s available much, much more quickly than clinical data, with data ready to be studied less than 30 days after the health care visit.

Consider the case of drinking water pollution in Hinckley, California, a story told in the movie “Erin Brockovich.” It took the Centers for Disease Control seven years to collect the clinical data that showed a link between drinking water and illnesses in the community — seven years of knocking on doors, reviewing medical charts, and entering data points one at a time until the full picture emerged.

“The movie came out before the data was published,” said Terri Lynn Palmer, former DHIN analytics contractor.

Claims data, had it been available at the time, could have cut that time to less than a year.

The combination of claims and clinical data — something that DHIN is uniquely qualified to process — can be invaluable to universities conducting medical research, studies seeking to pinpoint critical areas of the opioid epidemic, insurance companies evaluating the most effective forms of preventative care, and anyone looking to quickly detect trends in health care.

That includes the State Council for Persons with Disabilities, which found one group that was far more likely to receive follow-up care following a traumatic brain injury — teenagers, who as a cohort had a 45% follow-up rate, compared to 19% among the slightly older cohort of 20–39-year-olds.

“It was extremely helpful to work with DHIN in that regard,” Lancaster said. “We would say that we wanted data from this group or that area, and they would work their spreadsheets, because there’s so much that they can pull from the system.”

Why were kids more likely to get appropriate care? One possible reason is because legislation requires it — specifically the Concussion Protection in Youth Athletic Activities Act from Delaware Code Title 16, which requires a doctor’s note after a concussion in non-scholastic sports before kids can return to the field.

Could other types of legislation open the door for older people seeking care? Perhaps. Until then, Lancaster is using the data for another urgent need — education, for both patients and legislators.

“We’ve actually worked with DHIN to develop some infographics highlighting the disparities, but also highlighting things that people don’t necessarily understand, like the correlation between TBI and epilepsy or other long-term effects,” Lancaster said. “So hopefully we can continue to utilize the data, and bring more resources to Delaware, because ultimately, that’s the goal, to be able to support those with brain injuries here in Delaware.”

Read more from Spotlight Delaware